He Helped Columbus Discover Hockey

COLUMBUS, Ohio — You ask Doug MacLean about the reward of a full house watching this college town become a city in a major league, and the coach in him comes out immediately.

“It was a great night until the last two periods,” he moans.

That’s when the Columbus Blue Jackets blew a 3-0 lead Saturday night and lost to the Chicago Blackhawks, 5-3.

The real reward was a sellout crowd of 18,136 in the new Nationwide Arena watching Columbus join the NHL.

Just over two years ago, it was fantasy.

MacLean was sitting around the pool in South Florida when the call came from John McConnell, saying in essence, “Uh, Dougie, we have this NHL expansion franchise, and we’d kind of like you to come to Columbus and show us how it works.”

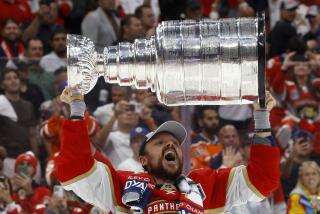

MacLean had time on his hands, courtesy of the Florida Panthers, whom he had coached into the Stanley Cup finals in only their third season, then was fired when it didn’t happen again.

“To be quite honest, when I got fired in Florida, the phone wasn’t really ringing off the hook,” he says. “This is the first job that came along and I wasn’t really being too picky.”

Maybe he should have been.

On Feb. 11, 1998, MacLean was introduced as the general manager of the Blue Jackets. A couple of months later, he was their president.

He also was the only Columbus Blue Jacket, which, by the way, is a slang expression for a Union soldier in the Civil War, something you won’t learn in Atlanta or Nashville.

“Now we have 200 employees,” he says.

Among the first was Jim Clark, the assistant general manager and MacLean’s friend since their days on Prince Edward Island in Canada’s Maritime Provinces.

“We met in second grade,” MacLean says. “My son is named after him.”

There was no team, no coach, no arena. For that matter, the populace was unsure what to make of all this, their confusion spurred in part by Ohio State’s desire to remain the only game in town.

So MacLean hit the streets, hustling hockey in first-down city. Rotary Clubs, the Elks, any civic club that called could get him.

“I pride myself in being a decent luncheon speaker,” he says, “but one day a guy came up and said to me, ‘Good speech. This is the seventh time I’ve heard you.’ I figured then maybe I’d better cut back.”

Once a coach more concerned with how often he could play John Vanbiesbrouck in goal, MacLean had to learn about negotiating concession contracts, radio-TV rights and building an organization.

He had to learn about construction, now that he is also charged with management of $150-million Nationwide Arena.

The hard part was all that and “trying to work time commitments, knowing that the most important part of the situation is still the hockey side,” he said.

Among those who came along for the ride was Sam McMaster, a former King general manager now living in Spokane, Wash., or more properly, living out of a suitcase while scouting the Western Hockey League and U.S. amateurs. The grand design of the Blue Jackets is no different from that of the Kings or Mighty Ducks or any other NHL team not headquartered in Manhattan:

Build through the draft.

It’s a slow, tedious process.

“Our bread and butter is going to be our first-round pick over the next three or four years,” MacLean says. “That’s going to make us. You look at Ottawa . . . at Colorado. Their best players have been their young players. Then you sprinkle in a few free agents. There’s no magic to it.”

The player budget is about $18.5 million, or about half that of the Kings or Ducks.

“The budget’s tight because I think it should be tight,” MacLean says. “I don’t think there’s any reason to spend more money right now. I could add a $5-million player and what good would it do?”

Absolutely none. Columbus has a few names you might recognize, but it is, after all, an expansion team and players are Blue Jackets because they were no longer wanted elsewhere.

Coach Dave King is better known to hockey cognoscente than to the mainstream as a former Canadian national team coach, college coach and assistant with the Montreal Canadiens.

Their leader, MacLean, is going through it all again, albeit on a different level. His resume says he took the Panthers to the Stanley Cup finals in their third season.

An encore isn’t likely.

“There’s no doubt that it’s one reason I had a chance for the job,” he says. “But I don’t think that will ever be challenged in pro sports, and not just hockey. For an expansion team to go to the final in three years, that’s pretty unique.”

That means one of a kind.

Not two of a kind.

“My owner asked me that in the interview and I told him that the only thing I would promise is that I would do it in less time than it took the Rangers between Stanley Cups,” MacLean said, laughing. “That’s 53 years.”

WHISTLE DERBY

The idea was more scoring. It’s always the idea in the NHL, which figures goals translate into tickets and higher television ratings.

And the idea was to protect the stars, to allow them to skate and work their magic without fear of being carved up by slashing sticks.

And the idea was to let the game flow without trips or holds or any of the other tools of the less talented.

But what’s happening in the early stages of the season is that referees are getting higher “Q” ratings than players, standing in front of cameras to signal yet another penalty. A league mandate to tighten enforcement of the rules has led to a population explosion in the penalty box and more power plays than five-on-five skating.

Last season, there was an average of eight power plays a game. So far, it’s 13.5, and savvy players needed about two shifts to figure it out.

Andy Murray and Craig Hartsburg are learning that they should have brought an out-of-work actor or two to King and Duck training camps.

Or maybe Greg Louganis.

“I think the integrity of the game is at stake,” says Murray, whose Kings had 16 penalties in their first two games.

The Ducks had 14.

“There’s so much diving going on, and it started in the first game of the season,” Murray said.

“Did you see it? Dallas and Colorado played a game like it was the Stanley Cup playoffs for a period. Then there were about 19 penalties called.”

A free-flowing hockey game turned into the last two minutes of an NBA game, a march to the free-throw line.

Patrick Roy of the Colorado Avalanche did a back flip without a twist, which probably has a high degree of difficulty because he did it wearing goalie pads. Whistle.

Players watched, and the stuff in the pool in Sydney, Australia two weeks ago has nothing on what NHL players are doing now.

And when they’re not diving, they’re going off the ice wringing their hands like Olivier, claiming slashes. And they’re getting calls. And power plays.

“I don’t blame the referees,” Murray says. “They’re doing what the league told them to do.”

Which means that they also can do what the league tells them to do when the league tells them to quit officiating the game and start policing it, which is the best way to call just about any sport.

McSORLEY, THE SPIN

Gary Bettman, once a lawyer, now the NHL commissioner, weighed in with the requisite opinion that the Marty McSorley verdict resolved an individual’s act.

“This was not a trial of the game or the NHL,” he said after just about everybody had opined that the trial was one or the other.

The trial sent NHL spinners to the archives, from which they gave Bettman this bit of trivia related by him Saturday night in Columbus:

“In 84 years, we’ve had eight incidents which have led to 12 players being indicted. Half of those players were indicted by the same district attorney in Ontario [over about two seasons].”

Bettman added that the league had punished McSorley much more severely than had the Crown. In that, the commissioner is right. British Columbia gave McSorley 18 months’ probation.

Bettman gave him life.

OH CAPTAIN, MY CAPTAIN

Minnesota Wild Coach Jacques Lemaire has decided on monthly captains, and the Wild’s first is defenseman Sean O’Donnell, whom the team got from the Kings in the expansion draft.

It’s flattering, and it’s part of a mutual admiration society.

“I can’t say enough about that guy,” O’Donnell said while in town to play against the Ducks. “It’s like playing chess: You’ll ask him what you should do, and he’ll say, ‘You do this, because the other guy will do this and the third guy will do that and you’ll be open.’ He sees things two or three steps ahead.”

The problem is that Lemaire is having to play chess with a board full of pawns, after having worked with royalty in Montreal and New Jersey.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.