Voters Turn Out in N. Ireland to Pick Assembly

- Share via

BELFAST, Northern Ireland — Elizabeth Leathen never thought it possible. In all her 77 years, the Catholic great-grandmother had never voted for a pro-British Protestant and couldn’t see herself doing so--until Thursday.

Choosing her six representatives to a new Northern Ireland government, Leathen cast her first vote for Sinn Fein, the political arm of the Irish Republican Army. Her last two votes were for Protestant parties that support the Good Friday peace agreement.

“It is amazing,” Leathen said of her own ballot. “But you know we have to get both sides together. They have to come together. And I wasn’t going to let those ‘no’ voters get into power.”

Call it a tactical move or a defensive block, the fact is that Leathen’s vote across religious and political lines represents a major step forward in Northern Ireland’s traditionally sectarian politics. And Leathen apparently is not alone. Many among the hundreds of thousands who turned out to elect Northern Ireland’s first self-rule government in a quarter-century may have cast votes for “the other side” in a bid to keep opponents of the peace accord out of government.

The 108-member Northern Ireland Assembly established under the agreement is to be shared by Protestants and Catholics. More than a dozen parties and independent groups fielded 296 candidates, some of whom oppose the power-sharing deal and vow to block its implementation from within the new government.

The accord delicately balances the will of Northern Ireland’s Protestant majority--most of whom want to remain in the United Kingdom--with the aspirations of Catholic nationalists, most of whom want to be united with the Republic of Ireland. The six counties of Northern Ireland were separated from the other 26 counties on the island in 1921.

The pact calls for Northern Ireland to remain in Great Britain unless a majority in the province votes to change this. Meanwhile, Britain will turn over day-do-day rule to the new Assembly, which will form a North-South Council to coordinate some islandwide policies with the Irish Republic. A Council of the Isles will join the governments in Belfast, the provincial capital, and Dublin, the Irish capital, with new legislative assemblies in Scotland and Wales.

Most important, the agreement attempts to take the decades-old battle between Northern Ireland’s Protestants and Catholics out of the trenches and move it into democratic politics with the aim of bringing an end to the bombs, executions and street riots that have taken more than 3,200 lives in 30 years.

But many voters on both sides are skeptical.

Protestants who oppose the deal view it as a slippery slope to a united Ireland. They say Sinn Fein should not be allowed into government unless the IRA hands over its weapons, and they do not trust Sinn Fein to stick with peaceful politics if nationalists fail to bring about a united Ireland this way.

Under the agreement, major decisions made by the new Assembly must be approved by a majority of Protestants and Catholics alike. The Rev. Ian Paisley, leader of the Democratic Unionist Party, has said that with 30 “no” votes in the Assembly, he can use this provision to block key elements of the agreement and bring about its collapse.

To Cara Thompson, 38, a Protestant mother of seven, that sounds like a good idea. “Those who thought they were voting for peace were voting for a united Ireland,” she said outside Edenbrooke Primary School in a Protestant neighborhood. “They [Catholics] don’t want peace. There was the proof yesterday when the bomb went off.”

The breakaway Irish National Liberation Army claimed responsibility for a car bomb Wednesday that destroyed the center of the southern town of Newtownhamilton and wounded a 13-year-old boy. The army is a nationalist splinter group opposed to the peace deal that sanctions British rule for the time being and to the IRA’s 11-month cease-fire.

In the wake of the blast, the 1,200 polling places across Northern Ireland were heavily guarded by police wearing flak jackets and patrolling in armored cars. There were no reports of violence.

About 20 of the Assembly candidates are former members of paramilitary groups who served time in jail for murder and other violence. One of those, Billy Hutchinson of the Progressive Unionist Party, described Thursday’s vote as “a chance for the people [of Northern Ireland] to get their hands on real power” and eliminate rule by distant British bureaucrats.

Hutchinson, who served 15 years of two life sentences for killing two Catholic brothers, said parties like his that support the agreement were trying to turn politics from life-and-death decisions “into bread-and-butter issues.”

Hutchinson, a Belfast city councilman, said he had received a telephone call earlier in the day from a Catholic woman who had gotten her whole family to vote for him. “She called me two weeks ago, and I sorted out a housing problem for her. She said no one else had done that. She said, ‘I just cast 18 votes for you.’ ”

The new Assembly will pick a 12-member executive committee from its ranks based on proportional representation. The government will oversee issues of health, education, agriculture and the economy.

Protestant hard-liners happily note that Northern Ireland’s only previous attempt to share power between moderate Protestants and Catholics was short-lived. That cross-community administration in 1974 crumbled in the face of a Protestant general strike and unrelenting IRA violence.

But this time Northern Ireland’s main armed groups have declared cease-fires and are represented by political parties running for election. Two major pro-British bands, the Ulster Defense Assn. and Ulster Volunteer Force, support the agreement and are working hard to get their political spokesmen elected to the Assembly.

On the nationalist side, Sinn Fein was competing for votes with David Hume’s Social and Democratic Labor Party. Hume, who helped woo Sinn Fein’s Gerry Adams into electoral politics, is one of the architects of the peace agreement. But even many of their supporters expressed skepticism about the possibilities for the success of the new Assembly.

“I voted for Gerry Adams,” said Jean Kelly, 53, a mother of five. “What do I want from the Assembly? Peace, fairness and justice. But we’ll never have it while we’re not a free Ireland.”

Charlie Murphy, 49, a watchman, said he voted for both the nationalist parties but was unable to bring himself to cross over and vote for a unionist. Some political leaders had encouraged supporters to spread their votes among the various parties that back the peace agreement. “It’s too soon for us to do that,” he said. “It will happen. Maybe in the next election we’ll vote for people who will deliver the goods no matter what they are.”

But the next election may be too late, said great-grandmother Leathen, who noted: “We have to let go of the past.”

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX / INFOGRAPHIC)

BACKGROUND

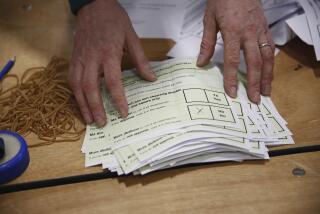

Balloting for Northern Ireland’s Assembly, a key part of the new government, was conducted under a proportional system. Each qualified individual got one vote. But voters also ranked candidates in order of preference. If the preferred candidate does not need the vote to get elected, that vote is transferred to the next preferred candidate, and so on.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.