Asia’s Transition: Pause for Breath

- Share via

HONG KONG — Economic doubts and fears have cast a pall over Asia, as the region that only yesterday enjoyed the world’s fastest growth enters a time of transition.

Stock markets are declining--or collapsing--almost everywhere in Asia. Paradoxically, such contractions often mean it’s a good time to invest, and Asia today is no exception. You or your mutual fund can find long-term value here, provided you understand the problems and underlying strengths of the region’s economies--and can wait a couple of years for a payoff.

Latin America and Eastern Europe are likely to grab the emerging-market spotlight in the next year or so, with Asia coming back to prominence in two years’ time--if its reform efforts succeed.

This is the autumn of Asia’s coming to grips with the surprises of the summer of 1997, which marked a point of departure for this region comparable to the 1989 fall of the Berlin Wall.

Hong Kong’s surprise has been pleasant, so far. The territory, which returned to China’s rule July 1, has awakened to a great opportunity as investment bank to the “great hinterland” of China. “We will be the New York of China, the financial center securitizing its state companies,” says Victor Fung, chairman of the Hong Kong Trade and Development Council.

It’s a role that could make Hong Kong the world’s biggest stock market in 20 years, if investors respond to China’s hunger for equity capital.

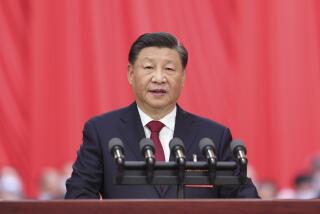

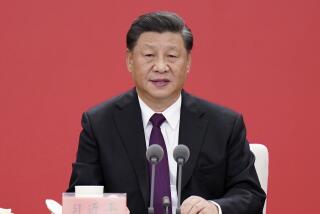

China surprised the world by the sweep of its ambitions, announced at its Communist Party congress in September, to sell stock in more than 300,000 state-owned companies.

Last week, Zhongyu Wang, chairman of its state economic commission, confirmed that China is thinking big money. Wang told 700 business people at the World Economic Forum in Hong Kong that China intends to sell stock in companies worth 4 trillion Chinese renminbi, or $500 billion. Eventually, Wang said, some of China’s companies will be “on the Fortune 500”--which was once the antithesis of Mao Tse-tung’s Little Red Book.

Meanwhile, the countries of Southeast Asia--Thailand, Malaysia, the Philippines and Indonesia--have recognized that currency devaluations, which began July 2, were only the first of many reforms needed if they are to regain the favor of global investors.

And the worst may not be over in Southeast Asia. Bad loans threaten banking systems, particularly in Thailand.

What does all that mean for economies and markets elsewhere? Some difficulties. Power plant and other projects negotiated at one currency level now must be renegotiated, and some projects won’t pan out at new prices.

Otherwise, however, the effect of slow growth in non-Japan Asia won’t be dramatic because the countries are not that imposing economically. Even China at, say, $800 billion in gross domestic product is equal only to California.

But Asia was looked to for new business and growing markets. Around the world there was a belief in the Asian way. And now there is skepticism, as was seen last week in the Hong Kong market’s response to the $4.5-billion initial public offering of China Telecom, a cellular phone spinoff of Beijing’s Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications.

The offer seemed a natural, a company set up to acquire and run mobile phone franchises for populous China’s chatty millions. But the response of institutional investors was lukewarm.

“Attitudes have cooled toward many of China’s companies,” explains Gary Greenberg, chief investment officer of Peregrine Asset Management in Hong Kong. Questions are being asked about whether China will follow up and allow the new companies to acquire assets and make industries efficient.

But patience is more useful than skepticism, says Joan Zheng, vice president for economic research at J.P. Morgan & Co.’s Hong Kong office.

Privatization programs will put people out of work, she explains, a sensitive matter in most parts of China, where there are no pensions or unemployment insurance.

So privatization will move slowly, Zheng says. “But that doesn’t mean a turning back. Privatization will be carried out over six years; a lot will be done by 2003.”

To understand this juncture in Asia, it’s well to step back and consider the underdeveloped economy that China really is. Trains don’t run on time, so few businesses ship by rail. On the other hand, long-distance transport is sketchy because roads need to be built.

Many state-owned firms lose money because they all jumped into manufacturing the same products. Thus there is a terrible glut of television sets, microwave ovens and refrigerators. Whirlpool is losing money along with Chinese manufacturers.

Such overcapacity means that any outsider who sees the 1 billion Chinese as a mass market for any product is crazy. The Chinese often supply their own products and lose money doing it.

But the very size of China’s output chills other manufacturers. Thailand, even though its currency has depreciated 40% since July, cannot compete with China.

So Thailand will have to find some way to add value to its products through research and development, or to its work force through an increase in high school education--a necessity that has been neglected in some other Asian economies too.

Yet for all the glut in Asia’s manufacturing, there are shortages in services, from management consulting to health care. In China and elsewhere, there are service industry opportunities crying out to be seized.

That’s where Hong Kong’s opportunity comes in. Its trained people will supply the investment banking, legal and business consulting to China’s changing economy.

The upshot: Asia’s economic troubles today, though indicating a need for reforms, are mild compared with the wars, cultural revolutions and political disasters of other decades.

That is why professional investors take the long view. “Nobody invests for under 18 months,” Richard Margolis, head of equity research for Merrill Lynch Asia, reminded a World Economic Forum audience last week. He said his firm is bullish on Hong Kong.

Jack Wadsworth, chairman of Morgan Stanley Asia, said his firm’s investment opinions are “overweight Hong Kong, India, Indonesia and Korea--where we like strong balance sheets.” He was unfazed by the severe tumble in South Korean stocks last week.

Just as prominent local businessmen take the current slowdown in stride. “What’s going on is called consolidation. You can’t have everything zooming up all the time,” says Gordon Wu, a master builder of projects in Hong Kong, China, Thailand and elsewhere for 39 years.

“But don’t write China and Asia off,” says Wu, whose Hopewell Holdings is currently building toll roads in China’s Pearl River delta. “This is where the people are”--a reference to half the world’s population, an underlying economic strength.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.