Why London Sizzles as Paris Fizzles

- Share via

Anyone who wants a practical lesson in comparative political economy should take a flying visit to Paris and London, which increasingly function not just as the capitals of their countries but also as the symbols of pre- and post-Thatcherite Europe. The two cities are only 200 or so miles apart--far closer than Los Angeles and San Francisco--yet their moods could hardly be more different. London is on a roll--vibrant, upbeat, brimming with optimism; Paris, on the other hand, is sunk in the slough of despond. The word on every Parisian’s lips is “morosite.”

Parisians are right to be gloomy. This most beautiful of cities is visibly degenerating--”a city of sequined architecture whose mascara is running,” as a French newspaper recently put it. The new Opera Bastille is swathed in netting, because bits have started falling off. And the Grand Arche de la Defense has already shed 35,000 marble tiles. Things are likely to get worse. The city’s capital spending fell from $1.54 billion in 1993 to $1 billion this year, while its debt swelled from $686 million to $2.74 billion, indicating that Paris is squandering its money on salaries rather than investing in infrastructure.

The property market, which went into a tailspin in 1992, continues to stagnate. Between the first quarter of 1996 and the first quarter of 1997, vacancy rates in Paris increased from 7.2% to 8%, and the capital value of property fell from $12,156 pounds a square meter to $9,159 pounds, according to Richard Ellis, a property consultancy.

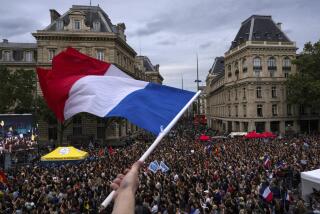

Strolling the world’s most romantic boulevards, you are more likely to run into throngs of unemployed youths, getting blotto on cheap wine, than you are to see star-crossed lovers. The Parisians are sunk in such a depression because they realize their system of state planning is dying, incapable of dealing with a borderless world of fleet-footed entrepreneurs and flexible companies, yet they lack the nerve to embrace the only viable alternative--Anglo-Saxon capitalism.

It is not all gloom, of course. Those shops that have remained open are frequently magnificent gleaming emporiums of diet-destroying desserts and spectacular cheeses. As far as many Americans are concerned, Paris is still synonymous with good living, the home of the world’s finest restaurants and most imaginative fashion.

Yet, prices are so high that Parisians outside the pampered establishment can do little more than window-shop. Anyone who wants to eat Korean or Thai rather than cholesterol-sodden French food is in for a long walk. Most humiliating of all, British designers have begun to storm the great French fashion houses. Givenchy recently appointed Alexander McQueen, a chunky East Ender, as its chief designer; Dior installed another Brit, John Galliano.

At the heart of Paris’ problem is the French unemployment rate, now approaching 13%. (Britain’s is under 8%.) The consequence of this can be seen not only in all the people sitting around, killing time, but also in the steady rise of racial antagonism. Parisian street life is all too often disturbed by clashes between the fascist National Front (now the third largest political party) and alienated immigrants, many of whom are attracted to radical Islam. Above all, the consequences can be seen in the bloody-minded belligerence of the average French worker, and the ostrich-like pose of the average bureaucrat.

Paris’ manufacturing sector, disproportionately large by the standards of most modern cities, has been hit hard by the “franc fort” policy necessary if France is to join Europe’s common currency in January 1999. But the city’s financial and service sectors are far too small and sluggish to fill the gap--little more than a “petit quatrierne,” according to the Parisians. Paris accounts for only about 4% of the world’s foreign exchange dealing, compared with London’s 30%; and Paris’ legal and consulting sectors are antiquated and parochial, geared to local markets rather than global ones.

The result is that, whereas London has been growing more rapidly than the rest of the British economy since the early 1980s, powered by its turbo-charged service sector, Paris has barely kept up with the rest of France. Museum employees are even doing their best to undermine the one industry in which Paris has undisputed preeminence--tourism. Visiting the city a few weeks ago, I found both the Pompidou Center and the Louvre closed, their “functionaires” on strike for more pay for less work.

If the French are sunk in morosite, the mood in London is tinged with exuberance. London is in the midst of a boom born of low inflation, declining unemployment and rising productivity. To be sure, there are terrible pockets of poverty--housing projects where a culture of welfare dependency and casual law-breaking has put down deep roots--but what strikes the visitor is not so much these legacies of the past but the promise of the future.

London is well-placed in those sunrise industries that require brains rather than brawn, creative flair rather than cheap labor. London is the world’s largest international-banking center, home to more foreign banks (524) than all France (170). British Telecom, a joke when it was run by the government, is now a global player. Soho is perhaps the most vibrant square mile in any city outside Asia and the U.S., a mecca for film producers, publishers, fashion designers and Internet entrepreneurs.

Signs of the boom are everywhere. Office-vacancy rates are falling and rental values rising. House prices in the more fashionable parts of town have risen by a third since the start of the decade. Prime Minister Tony Blair, who has been forced to sell his house in Islington for security reasons, looks set to make a quarter of a million pounds on a property he brought just a few years ago. When Terence Conran opened a 750-seat restaurant, Soho denizens said he was courting disaster. The place is buzzing.

Prosperity is reinforcing racial integration. “Afro-Saxon” culture is flourishing, with black writers such as Ben Okri, black dance companies such as Phoenix and black musicians such as Tricky. In Paris, immigrants are isolated in dingy suburbs, many of which are in a near-incendiary state; in London, Rastafarians and “trustafearians” (bright young things living on trust funds) live side by side in hot Notting Hill.

One reason for the difference between the two cities is that the British have passed the tests required to win admission to the new global economy, whereas the French have flunked them. Under then-Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s mixture of vision and stubbornness, the British made a series of painful decisions in the 1980s--from privatizing state industries to slashing subsidies to easing state regulations--that have turned the economy into one of Europe’s strongest.

French President Jacques Chirac and his right-wing prime minister, Alain Juppe, spent years promising similar reforms--and then caving in to vested interests. No sooner did French truck drivers blockade Paris with their juggernauts last November, for example, than Juppe allowed them to retire, on full pension, at age 55. A few weeks ago, a disgusted electorate swung left, electing a prime minister who promised to cut working hours, increase wages, create jobs and, presumably, fit every French pig with a pair of wings.

For all their mounting problems, the French continue to rail against Anglo-Saxon capitalism. They boast that they value compassion over competitiveness, social cohesion above economic efficiency. But what is compassionate about a system that condemns growing numbers of school graduates to unemployment; and what is cohesive about a system that pits interest group against interest group in the struggle for state largess?

The French blindness to the laws of economics can be seen in a particularly nauseating form on the streets of Paris, which are strewn with dog excrement. The government employs a small army of public servants, equipped with motorized scooters and fancy scoopers, to clean up the mess, but fails to impose significant fines on dog owners who allow their animals to foul the pavement in the first place. The result is that the supply far exceeds the capacity of these technologically empowered workers to deal with it.

The British were unenthusiastic about the Channel Tunnel, fearful that everything from their food to their clothes would elicit Gallic scorn. It turns out that the people who have something to fear are the French. It is impossible for a Londoner to make the trip from London’s Waterloo Station to Paris’ Gare du Nord these days without feeling a delicious sense of pity--rather as one does when visiting a once glamorous but haughty relation who has gone hopelessly to seed.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.