How a Man Lives Is His Legacy

- Share via

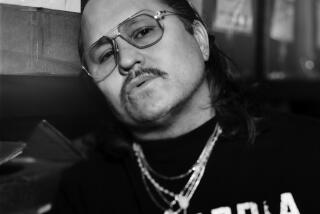

Fifty-three years after he first came to this country, my father, Julio V. Contreras, became an American citizen at the age of 75. With noncitizens soon to be denied many benefits, some people might question my father’s motives for embracing U.S. citizenship in the evening of his life. They’d be wrong.

You see, my father had only six years of schooling before he left Mexico. But he taught me and my five brothers more about citizenship and what it means to stand up for our rights as Americans than anything we learned in school.

He came to America as a bracero farm worker during World War II and put down roots in the small Tulare County farm town of Dinuba. He met my mother, Esther, in the fields. They married and had six sons; I’m the fourth.

He labored most of his working life on the same 400-acre grape and tree-fruit ranch. As we turned 4 or 5, all of his sons worked there, too. Agricultural experts from Fresno State would come to test the fruit for sweetness, color or texture. My father could tell by looking. He knew how much water and sun the fruit had received that season, and how it was pruned. He never had his name on the boxes, but my father took great pride in raising the best grapes and nectarines.

We almost moved to Los Angeles in the early 1960s. The family was outgrowing the tiny one-bedroom shack with outside toilets where we lived on the farm. The grower, Mr. Anderson, pleaded with my father not to go. He promised wood to build extra space onto our shed. Six years later it was condemned by the county. My father bought a little burned-out house in town. We tore down the shed and used the wood to rebuild our new home.

None of us ever talked with the next owner, L.R. Hamilton, all the years we worked on his ranch, even though we’d see him driving his big blue Cadillac by the fields.

By 1969, our family had become activists with Cesar Chavez’s United Farm Workers. We traveled on weekends to the Bay Area to leaflet at supermarkets for the grape boycott.

One hot day in July 1970, Hamilton gathered about 250 of his workers in a large tractor shed. He explained how he and all the grape growers were being “blackmailed” by the grape boycott into signing UFW contracts. He said railroad carloads of his grapes were returned unsold from Boston. Some of the workers yelled “Viva Chavez!” and threw their hats in the air. My father was among them. Hamilton angrily got back in his Cadillac and sped away.

For three years, my father was the elected head of the union committee at the ranch. I was a member, and we spent hours dispatching workers to jobs from our kitchen table.

All that changed at 4:30 on the morning that our three-year UFW contract expired in 1973. The ranch supervisor and crew bosses assembled the entire Contreras family in front of our little home and with the headlights from their pickup trucks shining in our eyes, they fired us all. “Julio,” the supervisor told my father, “you’re the best worker we ever had, but we can’t have any more Chavistas.”

All my father had to show for 24 years of hard labor on that land was being put on the growers’ blacklist of UFW supporters who were not to be hired. I knew how much my father was hurting, but he didn’t let it show. If he showed defeat as head of the union committee, then everyone else would be defeated, too.

My father led the strike at L.R. Hamilton. I was arrested 18 times in three months for violating anti-picketing court injunctions that were unconstitutional. He was arrested more than that. This was the still the era of the ‘60s; getting arrested wasn’t a big deal for me. It was for my father. He had never been arrested before. He always paid his taxes and obeyed the law. Even in the hardest of times, my father never accepted welfare.

Julio Contreras taught his sons the same lessons about courage and self-worth that farm workers learned from Cesar. Neither man thought of himself or the others in the fields as the growers did--as farm implements. They showed us that we must stand up and fight nonviolently for what’s right; we couldn’t be docile.

There were other lessons. My father taught himself to read and write English. He made his sons read and study. All around us, our cousins and friends were dropping out of school. Our father wouldn’t allow it. Three of my five brothers have college degrees; all of us have good jobs. One son fought in Vietnam, in the Army Airborne.

And we all are good citizens. We vote in every election--even for the mosquito abatement district board.

Why did he become a citizen now?

It’s his way of fighting back against the current anti-immigrant hysteria. By voting, he wants to show his grandchildren what he taught his sons on the picket line 24 years ago: the importance of taking a stand for what is right. He taught us the responsibilities of citizenship long before he became one.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.