New Hawaiian ‘Island’ Schooling Scientists

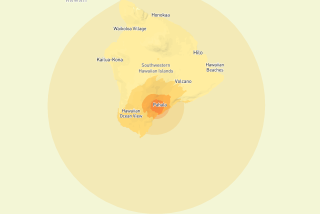

HONOLULU — Just off the beaches of the island of Hawaii, a new island is slowly forming from a volcano 3,000 feet below the ocean’s surface.

Researchers using a three-person diving craft are monitoring the volcano, named Loihi--Hawaiian for “Long One”--about 20 miles off the southern tip of the largest and southernmost island in the Hawaiian chain.

“It’s an adrenaline-charged trip,” said Alexander Malahoff, director of the Hawaii Undersea Research Laboratory. “You have to be extremely cautious and careful.”

The small, battery-driven craft, similar to an undersea spaceship, collects rock and water samples. It also deploys instruments and takes photographs in the sunless depths. A normal trip lasts eight hours.

Scientists have made about 60 dives in the submersible Pices V and taken 40 dives in other submersibles.

Loihi was discovered in 1955, but it wasn’t until the 1970s that a series of earthquakes led scientists to believe it was more than an elongated, inactive seamount.

The young volcano is growing so slowly that it will not break the ocean’s surface for 50,000 years, Malahoff said.

Loihi, which is about 13,000 feet tall, put on a show last summer, registering more than 4,000 earthquakes in a five-week span, said Fred Duennebier, a professor of geology and geophysics at the University of Hawaii.

More than 40 of the quakes registered a magnitude of 4.0 or more, according to the U.S. Geological Survey’s Hawaiian Volcano Observatory. A quake of magnitude 2.5 to 3 is the smallest people generally can feel.

The earthquakes toppled Loihi’s summit, an area called Pele’s Cone--named for the Hawaiian goddess of volcanoes. The cone collapsed into a pit crater 1,000 feet deep, filled with 300 million tons of rock--the equivalent of 50 million dump-truck loads--Malahoff said.

“The whole summit had been trashed,” he said. “Lava flows were destroyed. The whole landscape had changed.”

Scientists believe magma--underground lava--drained down from a chamber inside the volcano. When that happened, the summit collapsed. It could have caused a tidal wave, but it didn’t because the breakdown happened over three days, Malahoff said.

The drastic change produced new hydrothermal vents, where magma-heated water escaped into the ocean, overhangs and cliffs.

The colors of the volcano’s surface reflect the activity within. Reddish tones come from iron-rich minerals. White, fluffy material, primarily around the vent regions, is a mat of bacteria. Newly deposited lava is black and shiny, while older lava is a duller, reddish-brown color, said Jim Cowen, a professor of oceanography at the university.

Water temperatures around the vents can reach 140 degrees. Normal ocean temperatures at that depth are near freezing, Cowen said.

Loihi shares a “hot spot,” or volcanic ocean-floor source, with its larger active siblings, Mauna Loa and Kilauea, both on the island of Hawaii.

Research on Loihi is funded by the federal government, primarily the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which contributes $2.5 million to $3.5 million a year for the Hawaii Undersea Research Laboratory.

Researchers hope to improve their information-gathering techniques by laying an AT&T-donated; fiber-optic cable from the volcano to a small lab on the Big Island’s east coast. The system will create the Hawaii Undersea Geo-Observatory, or HUGO.

The cable will stretch about 30 miles and will serve as a power source for experiments. Researchers will be able to glean information about earthquakes, tsunamis (earthquake-generated tidal waves), temperatures and various underwater sounds through an underwater microphone, Duennebier said.

“I’ve done an awful lot of work on the ocean floor, and I’ve literally had to throw experiments off the side of the ship and hope they work,” Duennebier said.

The geo-observatory, a $2-million project funded by the National Science Foundation, will provide data faster and easier than the old methods, he said. The cable is expected to be laid in September, and the experiments could begin immediately afterward, Duennebier said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.