A Student of the Game

- Share via

LANCASTER — Given access to a major league ballpark--which most 8-year-olds would see as the world’s largest jungle gym, full of stairs and tunnels and places to run wild--Dusty Wathan chose the least likely alternatives.

Sit. Watch. Learn.

Nancy Wathan used to be shocked at how her second-grader would sit calmly at Royals Stadium, watching his dad, John, who was the catcher for the Kansas City Royals.

And when the family met after the game, little Dusty would pop off with something like, “Dad, how come you guys bunted in the seventh inning? Wouldn’t a hit-and-run have been better?”

“I was amazed at such an early age how much he grasped the game,” said John Wathan, now a part-time television commentator on Royals broadcasts. “He had his share of times where he was playing with the other (players’ sons) in the tunnels, but we were always amazed how much he watched the game.”

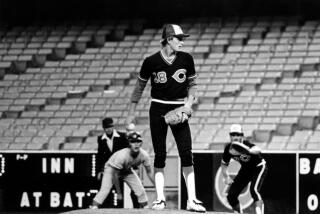

It is paying off now for Dusty Wathan, the Lancaster JetHawks’ 23-year-old catcher. Wathan is one of the top catchers in the California League, thanks in part to the major league knowledge and work ethic he soaked up in years of hanging around the Royals.

Wathan is not like Barry Bonds or Ken Griffey Jr., major league sons who took their fathers’ talent and multiplied it. Wathan, who now says he was “almost terrible” in high school, was passed over in the draft in three different years.

Wathan (6 feet 3) does not have a cannon arm. And he may be the slowest non-pitcher on the JetHawks. “He got his mother’s speed,” said his father, who holds the major-league record for stolen bases by a catcher.

But Wathan, signed as a free agent out of Cerritos College in 1994, has worked himself into a position where he, and his instructors, believe he has a legitimate shot to make the major leagues.

“If you would have seen him when we first got him, he’s improved 100%,” said Roger Hansen, the Mariners’ roving catching instructor. “Nowadays to find a catcher is so tough. Especially with expansion coming up, if you can catch and throw, you’ve got a chance (to play in the majors).”

Wathan is having his best season defensively. Mostly because of improved footwork and a quick release, he has thrown out 50% (38 of 76) of runners attempting to steal. (The Cal League record is 52.6%, set by Hideyuki Yasuda of Salinas in 1991).

And Wathan is batting .306.

“I think I’ve made quite a bit (of improvement),” said Wathan, who batted .252 in his first three pro seasons. “I think I’ve improved just from last year, defensively. And offensively, just playing every day helps a lot.”

Watching every day can help too.

Wathan was three when his dad made the major leagues, so going to the ballpark was the only life he knew.

Wathan often went to “work” with his dad. He hung around in the clubhouse before games, chatting with George Brett or Bret Saberhagen or Bo Jackson. And once the games began, Wathan spent most of his time glued to his seat.

“I would go and screw around for a couple innings here and there like any 9- or 10-year old,” he said, “but I’d watch a lot of the game. I think from watching baseball and watching situations, that’s the way you learn. No matter how long you watch baseball, there’s always going to be a situation come up that you haven’t seen before.”

Wathan would often take what he had learned from the Royals and bring it to his own Little League games, which wasn’t always appreciated.

“He had one coach, when he was 10 or 12 years old, and he knew more than the coach, and I think the coach really resented it,” John Wathan said. “Because Dusty had such a strong personality, they would knock heads once in a while.”

Added Dusty: “When I was 9, I had probably seen as many games as most adults had seen, and I probably had a little better insight into the game.”

One of Wathan’s favorite ballpark moments was when he was about 15. He was taking some swings in the batting cage when he heard a voice say: “Keep your hands back.” Wathan looked around, and saw the instruction was coming from his idol, Carlton Fisk, then with the Chicago White Sox.

Wathan’s own baseball games began to take precedence over his father’s as he grew older. Even though he was a star at Blue Springs (Mo.) High, he figured he wasn’t good enough to be drafted. And he was right.

He got offers to play at four-year colleges, but signing with one of them would have meant waiting three more years to be eligible for the draft. So Wathan went toward the warm weather of Southern California. He spent a year at Orange Coast College and then transferred to Cerritos, getting overlooked in the draft again after both seasons.

In the summer of 1994, just after a disappointed Wathan headed for the Cape Cod League, the nation’s premier college summer league, the Mariners called, saying they needed a catcher for their rookie-level team in Peoria, Ariz.

Wathan signed, and breathed a sigh of relief because he could finally begin pursuing his dream. But he quickly learned the meaning of the phrase: “Be careful what you wish for, you might get it.”

“I got to rookie ball,” Wathan said, “and I’m going, ‘God this is terrible.’

“No one realizes what rookie ball is like unless you’ve been there. You can’t fathom it. There is nobody (at the games). And when I say nobody, I mean nobody. Zero.”

Wathan spent 1994 in Peoria. He stayed there in 1995 for the only thing worse than rookie ball: extended spring training. They play in the same 100-degree heat on the same minor-league fields with the same empty bleachers, but at least in rookie ball, the games actually count.

Wathan played briefly at Class-A Wisconsin in 1995 and finished the season at Class-A Everett, Wash., before playing all of 1996 with the JetHawks. It was a big jump for Wathan, and he struggled at times. Complicating matters, he was playing sporadically and dealt with several nagging injuries.

“This time a year ago I might have been thinking, ‘Wow, I don’t know if I can do this. I don’t know if I’m good enough,’ ” he said. “But I never thought about quitting.”

The story is far different now. Wathan is playing the best baseball of his life. Three years of defensive drills have finally paid off, helping him be consistent with his mechanics and deadly for opposing runners.

“It’s almost been to a point where I hope guys go, because I want to throw them out,” said Wathan, who has thrown out three or more runners in six games.

Hansen, the Mariners’ catching guru, said Wathan “has really worked his . . . off to get to the point he is. Now it gets harder.”

The next step is the toughest. Some say the jump from Class A to double A is the biggest in baseball. It is where the true major league prospects and the fillers often are separated.

But if he doesn’t make it to the majors, Wathan probably still has a long baseball career in his future.

As a manager.

“I kind of like that side of the game,” he said. “It seems like it would be a real challenge to get everybody’s personalities to come together as one. Plus, you have to out-think the guy on the other side.”

And Wathan has been preparing for that job since he was 8 too.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.