Couch Potato Heaven : DEFINING VISION: The Battle for the Future of Television.<i> By Joel Brinkley</i> .<i> Harcourt Brace: 402 pp., $27</i>

- Share via

On Dec. 26, almost 10 years after announcing an all-out competition to develop an American high-definition television system, the Federal Communications Commission finally approved the first major change in television technology since color TV in the early 1950s. Along its rocky way, that technology had changed from analog to digital and with that innovation, high definition became just one of many possible applications. Digital televisions will someday be computers that can bring viewers e-mail, video mail and Web sites just as easily as sitcoms. Now, in his perfectly timed book, Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter Joel Brinkley, a New York Times editor, tells the sordid, bewildering and always entertaining tale of the race to create that new system.

A historian once described the development of television in the 1920s and 1930s as “a lengthy episode fraught with contradictions and unsubstantiated claims and spiced here and there with commercial politics.” His words apply equally well to Brinkley’s story; in fact, the parallels between the two histories are striking: Years of research boiling down to last-minute preparations, nerve-withering demonstrations in Washington hotel rooms, backbiting machinations between company executives and the Federal Communications Commission watching over it all, a clueless referee. Special emphasis, however, should be applied in the case of digital TV and “commercial politics.” The principals involved here performed skulduggery worthy of the dirtiest of elections, beginning with a shameless ploy by a group of broadcasters.

If not for Brinkley’s exhaustive reporting, the world might never have known that digital television arose from a greedy ruse to fool the FCC. In the mid-1980s, the mobile communications industry made a bid to take control of the copious television spectrum that wasn’t being used. Television broadcasters instinctively were aghast; after all, this spectrum space was enormously valuable. Unfortunately, the broadcasters had absolutely no use for the extra channels. They desperately needed to find a reason to keep the channels. Enter HDTV.

The National Assn. of Broadcasters brought NHK, Japan’s television network, to Washington in January 1987 to demonstrate its new HDTV system--a normal analog system with twice as many lines per picture. Its pictures were stunning and had exactly the desired effect. Japan was going to steal the next generation of television technology just as it had stolen almost the entire consumer electronics industry. A wave of xenophobia crashed over Washington, and HDTV became the newest national crusade: “High-definition television would bring back America’s failing consumer electronics industry. It would create tens of thousands of jobs, maybe hundreds of thousands. . . . HDTV would eliminate the trade deficit, pay off the budget deficit! It would lead America to Nirvana! And with that, in very short order, Washington fell into an HDTV frenzy.

“ ‘We’re fighting for the future of HDTV!’ a broadcast industry lobbyist exclaimed. . . ,” writes Brinkley. “A few months earlier, this lobbyist probably couldn’t have said what those initials stood for.” The FCC took the bait anyway: It forgot about mobile communications and formed the Advisory Committee on Advanced Television Service to foment the creation of an American HDTV system. A competition was announced, and 23 proposals promptly hit the committee’s desk. All were analog. Then, in June 1990, a small San Diego division of General Instrument, VideoCipher, announced that it was entering the contest with a digital system. Many labs had been working on digital video for years, but it was widely assumed that it would not be feasible for television before the turn of the century. After GI’s announcement, though, other companies realized that they too could go digital. Analog HDTV was suddenly a dream of the past.

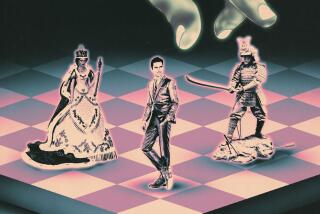

Drawing on all of his prize-winning reportorial powers, Brinkley uses personal memos, letters and even journals, and takes the reader to private dinners, meetings and conversations to dramatize the tortuous tale that followed. Scientists, CEOs, Japanese business moguls, FCC commissioners and senators file on stage to play their roles of instigators, innovators, matchmakers, mediators and villains. John Abel of the National Assn. of Broadcasters comes to life as the Machiavellian lobbyist who conjured HDTV as the broadcasters’ spectrum savior. Jae Lim of MIT, one of Brinkley’s supporting characters, is the humorless self-righteous patriot who refuses to compromise. And Dick Wiley, former FCC commissioner and chairman of the advanced-television committee, makes a fine leading man as the elder statesman, an expert diplomat and hard-nosed politician, who cajoles, threatens and ignores as the situation dictates, shepherding digital TV from its first mewling appearance to its eventual incarnation as a system suitable for recommendation to the FCC.

Wiley’s greatest triumph is to convince the remaining eight contestants to forget their differences and form a grand alliance, combining the best elements of their various systems into a final indomitable machine. But even as partners, the players in this game cannot help but bicker, connive and sabotage each other. Zenith and AT&T;, who are supposed to collaborate on one part of the system, practically hiss at the mention of one another; they ridicule each other’s work and hardly try to hide it. The engineers at the David Sarnoff Research Center and MIT (plus the MIT graduates who dominate General Instrument), on the other hand, are portrayed as arrogant and pompous, barely able to stand sharing their work with inferior minds. In creating these antagonistic archetypes, Brinkley unfortunately deviates from his usual prose--sharp, effective and unself-conscious--to rely on repetition of flat phrases. The Sarnoff labs are always “the Sarnoff Shrine;” MIT’s Nicholas Negroponte is “the Grand Vizier,” almost never referred to by his real name; and Jae Lim is forever “saving America!” It’s hard to believe that Lim truly felt he was the savior of his adopted homeland in demanding progressive, instead of interlaced, scanning.

But these overused phrases (and occasionally confusing chronological zigzags) are minor flaws in what is otherwise a superior work of journalism. Brinkley has fun with the endless litany of obstacles and enemies to the process of approving the new digital standard. Wiley must deal with computer industry lobbyists, who insist that the new television must be “interoperable” with computers, with a new FCC chairman who favors new digital services possible over HDTV and with John Abel. From the moment HDTV appeared feasible, Abel and the NAB turned face and began battling against HDTV. They never really wanted it in the first place; it was just part of their ruse to keep their spectrum. Now that digital TV was here, they wanted to use it in more profitable ways, such as offering various computer services or showing several standard-definition programs in the same spectrum space as one current channel.

It all makes for compelling reading. “Defining Vision” doesn’t really explain the technical issues involved in developing digital TV, but that’s just as well: They’re too complex and arcane for most readers. The emphasis here is on politics and intrigue, and there’s enough of both to rival John le Carre. Just as Sarnoff battled tooth and nail for bragging (and patent) rights to monochrome television in the 1930s and color television in the 1950s, so his corporate descendants waged a holy (and sometimes unholy) crusade for digital television in the 1990s. Late last year, the final hurdle was cleared when the grand alliance agreed with the computer industry to let the free market decide exactly what form digital TV will finally assume. At long last, the viewers will take the stage.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.