A City That Still Is Consumed by Castro

MIAMI — He is the most influential man in the history of this city--and the most despised. Everywhere, every day, talk of Fidel Castro swirls through the air like smoke from a hand-rolled cigar.

“He is a dictator who brought pain, suffering and killing to Cuba. There is nothing, not one positive thing, about Fidel Castro,” says fiery radio commentator Ninoska Perez, barely lifting the lid on the reserves of passion and vitriol that the bearded Cuban leader evokes here. In private conversations, in print and on Spanish-language radio in this voluble city of exiles, it is all Castro, all the time.

More than four decades have passed since Castro last set foot in Miami and even then he was here only briefly. Yet no one is more responsible for shaping this ethnically complex metropolis, the city with the third-largest Latino population in the United States.

And no one casts a larger shadow over Miami’s future.

For years, local and state officials have been tuning up an emergency plan to deal with the inevitable explosion of emotion and movement across the Florida Straits if Castro were to die, be driven from power or go into exile. Chaos may not describe it.

But, despite the fervent prayers of Cuban exiles and the unrelenting hostility of eight U.S. presidents, no drastic change seems imminent. Today, Castro will mark the 38th anniversary of his rise to power in Cuba, while in Miami tens of thousands of people who fled his rule will celebrate another bittersweet New Year in exile.

Although proud of the cosmopolitan, international city that they have helped to build in south Florida, many Cuban Americans remain fixated on their homeland, just 220 miles south of here but politically out of reach. And they remain consumed with hatred for the man they believe stole their country from them.

“I remember when the plane took off and I was looking down at the land disappearing behind me,” says Spanish-language radio personality Tomas Garcia Fuste, recalling his departure in December 1960, almost two years after Castro’s triumph. “I thought it would be a long time before I saw Cuba again. But all these years? No, I could not have imagined that.

“I am old. Castro is old. But the situation is the same,” says Garcia Fuste, who is 66, four years younger than the Cuban president. “So of course we talk about him. We will never lose our enthusiasm for the fight against Castro.”

Castro is the graybeard among world leaders, and Cuba is now the only country in the Western Hemisphere that is not a democracy. Officially, Castro is the commander in chief of the armed forces, first secretary of the Communist Party and president of the Council of State and the Council of Ministers.

But among the domino players on Calle Ocho in Little Havana, to the men sipping coffee at any of a thousand street-side cafeteria windows, to the women in the grocery store and the beauty shop, he is known as el tirano, el diablo, bola de churre--the tyrant, the devil, the dirt ball--or by several other terms that newspapers do not repeat in English or Spanish. He is ridiculed constantly in jokes and stories.

In Cuban Miami, there is no greater insult--or a more dangerous identity--than to be labeled a Castro agent. Want to start a fight? Stand on a Little Havana street corner and say: “You have to admit that Castro isn’t all bad.”

The Cuban community’s sentiments are spelled out in car bumper stickers: “No Castro, no problem,” and “The only dialogue with Castro: Blindfold, yes or no?” Tempers still flare at the mention of a videotaped 1994 meeting in Havana when a Cuban American woman was seen bussing Castro at a reception. The only time the Cuban leader seems at all amusing is when popular Castro impersonator Armando Roblan breaks into La Macarena.

“It is not like Cuban Americans are planning ways to overthrow Castro every minute of the day,” says historian Maria Cristina Garcia. “However, the community’s raison d’etre is the Cuban revolution and so every aspect of exile life in some way is a response to this man.”

Indeed, although the majority of the nearly 1 million Cuban Americans in Greater Miami were either born in the United States or are too young to have much personal experience of life under Castro, hating him is a part of exile culture, passed on to succeeding generations like a taste for frijoles negros and fried ripe bananas.

Recent polls indicate that, were Castro to disappear tomorrow, most Cubans here consider themselves much too rooted in America to take up permanent residence on the island. Yet even those who know the island only from faded family snapshots and travel books are steeped in Castro revulsion.

“Cubans have redefined what assimilation means,” suggests Garcia, a Texas A&M; professor and author of a study of exiles in Miami called “Havana USA.”

“To Cubans, being American does not mean closing the door on your past,” she says. “They retain their Cubanness.”

There are several Spanish-language radio stations in Miami, which offer a daylong menu of Castro-bashing, and the most avid listeners are primarily older exiles, those who had the most to lose as the island became a socialist state. The majority of younger Cuban Americans are too busy with their lives to dwell on the dictator.

“It’s a waste of time,” says Ana Arenas, a 34-year-old teacher whose father was a political prisoner in Cuba before the family immigrated here in 1980 during the Mariel boat lift.

Yet no one is immune from at least overhearing the news of Cuba and the rumors and gossip about Castro--the state of his health, where he has gone, his libido--that whirl through Miami like the Caribbean breeze.

“My mother reads the paper, tells me about what is going on and I have uncles who keep up with it,” says Arenas. “I tell them that concentrating on Castro gives me a feeling of helplessness. But the older generation wants to hope, to think something is going to happen--and happen soon.”

Notwithstanding the fervent hopes of Cuban exiles, a punishing U.S. trade embargo, a faltering Cuban economy and periodic U.N. resolutions condemning the Cuban regime for human rights abuses, Castro remains firmly in charge--a dedicated Marxist, resistant to meaningful democratic reforms and still a player on the world stage. He hosted a delegation of current and former U.S. legislators last month and in November dropped in on Pope John Paul II in Rome. The Pope, in turn, is expected to make his first visit to Cuba this year.

That recognition of Castro’s legitimacy as a world leader only fuels exiles’ fury. One consequence of this hatred is an occasional outbreak of paranoia in which the hand of Castro can be seen behind whatever seems contrary to the interests of the Cuban community. Of course, according to popular belief, Castro personally gave the order in February to shoot down unarmed planes of the exile group Brothers to the Rescue. Four men died. But are Castro and his agents really responsible for street crime, Florida’s hurricanes and the editorial policy of the Miami Herald?

The community’s preoccupation with Castro also leads to a litmus test of political correctness that over the years has produced an ugly history of assassinations, fire bombings and intimidation and draped Miami with a reputation as a city where the American tenets of tolerance and free speech are often trampled. Two years ago Human Rights Watch, after yet another investigation of politically motivated violence here, concluded that “the overall climate for free expression remains essentially unchanged in Miami: only a narrow range of speech is acceptable and views that go beyond these boundaries may be dangerous to the speaker.”

The moderating influence of time and a few moderate voices in the exile community may have improved the climate for free expression. No one has been maimed or killed for failing the Castro test for 20 years. But the test is still invoked and violence often ensues.

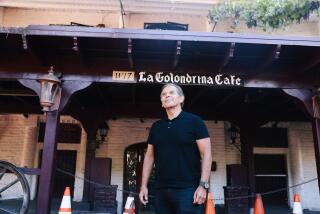

There are films which cannot be shown in Miami, musicians who cannot perform, plays that cannot be staged. In the last year alone, a popular Little Havana restaurant was firebombed in protest of a scheduled appearance by entertainer Rosita Fornes, protesters spit on people attending a concert by pianist Gonzalo Rubalcaba, and an art critic’s lecture and a dance band performance were canceled after threatened violence.

In each case the artists--all Cuban--were deemed by community zealots to have insufficiently distanced themselves from Castro.

But it is not just artists who are subjected to the test of political correctness. Twice in 1996, firebombs damaged offices of the travel agency owned by Francisco Aruca, an outspoken and controversial figure in the community who does business with the Cuban government and is often called a “Castro agent” on Spanish-language radio.

“It is ironic,” says Aruca, “that in Cuban Miami we ended up denying the democratic values that exiles supposedly came here to find. There is a low level of tolerance for freedom of expression.”

Officially, the Clinton administration takes the strong anti-Castro line of its predecessors, continuing the trade embargo imposed against Cuba more than 30 years ago. But as President Clinton begins his second term, with no need again to court the votes of hard-line Cuban exiles, many Cuban Americans suspect that he may act to improve relations with the Castro government.

The Immigration and Naturalization Service last week officially ended decades of favored treatment granted to Cuban migrants by agreeing to send back to the island even those refugees who reach U.S. shores. And by Jan. 16 the president must decide whether to extend the suspension of the most controversial aspect of a new law that would allow U.S. residents to sue foreign companies that use property seized during the Cuban revolution.

If the duration of their exile seems unimaginable to many Cuban Americans, so too does the city they have helped to build. In 1959, the year that Castro and his band of guerrillas overthrew the government of Fulgencio Batista, Miami was primarily a vacation spot for northern snowbirds and a port from which Americans embarked for Cuba and rum-soaked weekends in mob-run casinos.

Miami was also a city where ousted Cuban dictators sought refuge and rebels on the make sought funds for insurrection. Castro, after being granted amnesty for an earlier attack against the Cuban government, stayed in Miami in late 1955 while he raised money for his revolution.

After Castro’s victory, immigration from Cuba to Miami came in waves--beginning with upper- and middle-class Cubans in the early 1960s, continuing in a steady stream through the late 1960s and early 1970s, to the Mariel exodus of 1980 and through the rafter crisis of 1994. During Castro’s rule, almost one-tenth of the island’s population of 11 million has fled to this country.

That steady migration of Cubans across the Florida Straits has served to refresh the use of Spanish as a language co-equal with English and to shape Miami into a Havana Norte, a city that in many ways reflects exiles’ efforts to create here what they left behind. Over the years the Cuban presence also has made this city a mecca for other Spanish speakers, from Nicaragua, Colombia and other Central and South American countries.

Today, Greater Miami--with a population of 2 million--is a cosmopolitan capital of international trade and banking with a larger proportion of foreign-born residents--about 35%--than any other American city. Residents like to joke that one of the reasons they like living in Miami is that it is so close to the United States.

That foreign-domestic duality is no joke to sociologists; they see this city as a cultural laboratory where the future of other American cities is being previewed. According to Lisandro Perez, director of the Cuban Research Institute at Florida International University, Miami includes the best-defined ethnic enclave in the United States.

Here a Latino majority presides over distinctive economic and social organizations designed to serve their own ethnic market as well as outsiders. Here, it is not only possible but commonplace for residents to live out their lives within the ethnic community, conducting all their business and social interactions entirely in Spanish.

The institutional completeness of the enclave, Perez says, serves to reinforce the politics and opinions of the dominant segment of the Latino enclave, Cuban Americans. And for many, the dominant issue is reclaiming their homeland from Fidel Castro.

“Part of the exile community’s identity is a strong political message--anti-Castro,” says Perez. “And if that exile ideology seems frozen in time, it may be because U.S.-Cuba relations are frozen in time.”

With that freeze expected to continue, so too are the fascination, the hatred and the talk. Castro “is the person responsible for turning upside-down the lives of me, my family and so many others,” says Ninoska Perez, who came to this nation at age 7. “I blame him for not being able to live in my homeland for more than 30 years. So I guess we’ll still be talking about him as long as he is there.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.