Strict U.S. Sentencing Laws Are Tipping Scales of Justice

- Share via

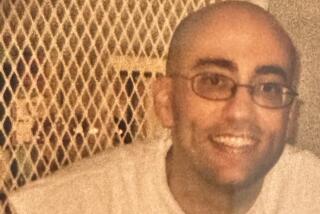

No one disputes Bobbie Marshall’s guilt--not even Bobbie Marshall. In 1990, he admitted selling 53 grams of crack cocaine from his mother’s house across the street from a Pacoima elementary school--a crime that normally should have earned Marshall every day of the 14-year sentence called for by federal law. After all, Marshall’s arrest capped decades of dealing and abusing drugs. If anyone deserved a long sentence, it was he.

Why is it, then, that the federal judge responsible for sentencing Marshall refuses to send the admitted drug dealer to even nine years in prison? The question lies at the heart of the historic tension between justice and punishment. Marshall’s case highlights that tension and points up the inequities inherent in a system that replaces judicial discretion with legislative dogma.

Free on bail in the early 1990s, Marshall had a revelation. He was emptying garbage cans at a park when he asked the park director whether he could teach kids weightlifting. From there, Marshall went on to counsel kids looking for a way out of gangs. He understood the pressures they faced. More importantly, the high school dropout understood the price of succumbing to those pressures. He worked to keep peace during the 1992 riots. Now community leaders, school officials, members of the clergy and even a United States congressman have appealed for leniency in Marshall’s sentence.

U.S. District Judge Terry Hatter agreed that reducing Marshall’s sentence served society better than locking him up. Although prosecutors agreed to reduce Marshall’s sentence to nine years, Hatter wanted half that--and still does. But a series of rules passed by Congress in the late 1980s prescribe to federal judges mandatory minimum sentences for some crimes and strict guidelines for others.

A federal appeals court already has struck down one attempt by Hatter to impose a lighter sentence. Hatter continues to postpone Marshall’s sentencing, but prosecutors are growing impatient. More than seven years after his initial arrest, Marshall still waits for his fate to be decided. In the end, Marshall will almost certainly end up with a nine-year prison term. Hatter can stall only so long before prosecutors petition a higher court to move the process along. Marshall’s lawyer has promised to ask President Clinton for a pardon or a commuted sentence, but it is highly unlikely that either will be granted.

Laws such as those limiting Hatter’s options appeal to an electorate that feels besieged by hoodlums and gangsters. These laws were designed to limit exactly the kind of discretion that would have allowed Hatter to reduce Marshall’s sentence. Voters wanted tough uniformity in sentencing and Congress obliged. As long as the offenders fit the anonymous statistical profiles of bad guys, longer standardized sentences sound like the answer. Rarely is it that simple, as Marshall’s case illustrates.

It’s tempting to deny Marshall any special consideration. He committed the crime and deserves to be punished. If tougher sentences are to serve as a deterrent, they must be imposed swiftly and surely. Judges should not be duped by jailhouse conversions. If a person like Marshall, with seven arrests and four convictions under his belt, can beat the system by proclaiming a new life, then how many others might use the same tactic to avoid federal prison?

But justice, like crime itself, is subject to individual circumstances. Wholesale regulations deny that individualism. They mete out standardized punishment, not justice. Where does Marshall do the most good to society? In prison, where he is a human liability sucking up tax dollars? Or on the street, where he can help keep others from straying? As it stands, we’ll never know. A reasonable compromise would be to give Marshall supervised probation, during which time he could continue his work with children and teens. If he fell back into the destructive patterns of his former life, even briefly, he would end up serving the full 14 years of his sentence.

Reasonable, maybe, but the law forbids it. Recognizing the inflexibility of California’s “three strikes” law, the state Supreme Court earlier this year gave judges the kind of discretion necessary to differentiate between criminals who deserve to spend the rest of their lives in prison and those who don’t. Federal judges lack that power in many cases and should have it back. A case like Bobbie Marshall’s doesn’t come around very often. But when it does, a truly just system should be equipped to deal with it.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.