Surgeon Gave 19 Hepatitis Virus

Beginning in July 1991, at least 19 people who underwent surgery at the UCLA Medical Center and a university-affiliated hospital contracted hepatitis B virus infection from a particular a surgeon, according to a federal investigation of the unusual outbreak released today.

The study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, does not say definitively how the unnamed surgery resident transmitted his hepatitis B infection to 13% of 144 patients he operated on over a year. But it strongly suggests that he developed small cuts on his hands while operating and that his own virus-laden blood passed through leaks or holes in his gloves.

It was the only documented U.S. outbreak of hepatitis B linked to a thoracic surgeon, but four such outbreaks have been documented in the United Kingdom, where cases have generally been traced to poor infection control.

The researchers said they found no evidence that the UCLA surgeon and his supervisors violated infection-control procedures, such as sterilizing equipment and antiseptic hand-washing. Nonetheless, medical researchers were critical of the surgeon for previously refusing a hepatitis B vaccine, which probably would have prevented his infection.

And contrary to the advice of UCLA experts, the surgeon did not wear double gloves once he returned to the operating room after a bout of acute hepatitis. “It would have been better if he had double-gloved,” said Dr. James Cherry, former head of infection control at the UCLA Medical Center. “We had talked about double-gloving and assumed it would happen, but it didn’t.” Cherry was a coauthor of the CDC-led study.

Commenting on the outbreak in a journal editorial, Dr. Julie Louise Gerberding of UC San Francisco said that additional operating-room measures, including reinforced gloves and less abrasive suture needles, might be called for to reduce virus transmission. “Changes in surgical technique, improved barrier materials, and the use of less invasive alternative procedures can all contribute to a safer surgical environment,” she said.

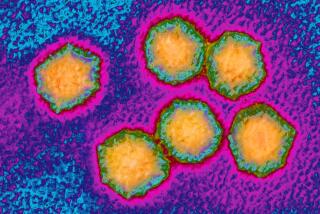

The hepatitis B virus, which infects the liver, is most commonly transmitted by exchange of body fluids during sex and sharing of contaminated needles by drug addicts. An infection can cause serious acute illness or virtually no symptoms. About 10% of those infected have serious chronic disease, and some of them develop liver failure or liver cancer.

In the UCLA outbreak, the infected persons ranged in age from 14 months to 83 years. An undisclosed number of the victims, who remain anonymous, filed lawsuits against the medical center. The cases were settled out of court, said CDC medical epidemiologist Rafael Harpaz, the study’s lead author.

As soon as the first infected patient came to light, the UCLA surgeon was removed from surgical duties, a university spokesperson said. In the investigation, the surgeon cooperated with CDC investigators, donning latex gloves for an hour and simulating his suturing technique, which resulted in barely visible abrasions on his skin. He had so much virus in his blood that the researchers readily detected hepatitis B virus inside his gloves.

According to Cherry, the physician has left California and is not currently performing thoracic surgery. “It ruined his career, the way he looked at it,” Cherry said.

The risk to patients of contracting hepatitis B from health care workers remains very small, Harpaz said. He pointed out that no similar U.S. outbreak has been documented in the four years since the UCLA problem appeared. “The risk of transmission can be expected to go down even further as more doctors are vaccinated,” Harpaz said.