Mexicans Turn May Day Into Massive Protest : Latin America: With labor’s annual parade canceled, more than 100,000 gather in the capital to denounce Zedillo’s economic plan.

MEXICO CITY — More than 100,000 angry workers, teachers, scientists, students, farmers and homemakers filled the streets here and in several state capitals Monday, transforming this nation’s traditional Labor Day celebration into a huge protest against President Ernesto Zedillo and his economic policies.

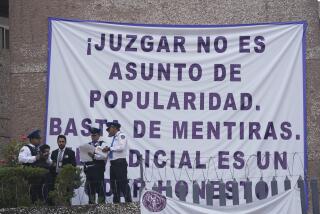

The capital’s main boulevards and downtown square turned red this May Day with homemade banners, floats and slogans denouncing the president’s harsh economic emergency plan, praising the armed rebel movement in the southern state of Chiapas and demanding that Zedillo’s predecessor stand trial.

The daylong protest was largely peaceful.

After a brief stoning episode involving a small group that broke from the marchers--whose total was estimated to exceed 100,000 when they gathered in the Zocalo plaza beside the National Palace--riot police again withdrew into the background.

Most Mexicans steered clear of the marches. Amid fears of potential violence, many simply stayed home. Commerce and traffic across Mexico were at a holiday standstill.

But Monday’s large, spontaneous turnout--and its accompanying fury on a day traditionally reserved for orchestrated, pro-government praise on the streets--appeared to be yet another sign of the eroding support for Mexico’s ruling party, especially from the once-monolithic labor groups that have helped keep the Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI, in power for 66 years.

The stage for the opposition’s show of force Monday was set last month when Mexico’s loyal labor leaders decided to cancel the official annual May Day parade for the first time in 74 years.

Conservatives in labor, led by 95-year-old Fidel Velazquez and the 10-million-member state-controlled Labor Congress, blamed the cancellation on a lack of money and the potential for violence amid the nation’s worst economic crisis in more than a decade. The decision also cleared the way for hundreds of Mexico’s growing independent labor unions and thousands of special-interest groups to use the pro-labor May Day holiday to attack Zedillo’s government and party on several fronts.

At the only official ceremony--a brief, early session attended by about 5,000 pro-government unionists at the Railway Workers Auditorium--Zedillo defended his economic austerity measures. They have sent interest rates, prices and unemployment soaring as part of a crisis that the government estimates will cost at least 500,000 workers their jobs.

“Overcoming the crisis has demanded very difficult measures,” Zedillo conceded. “There are no easy recipes or agreeable paths to resolve the problems facing our economy. The route that we have chosen is the shortest and has the least social cost.”

He insisted that his government has not “abandoned its social responsibility to Mexican workers” and announced that the austerity plan has begun to pay off with newly stabilized financial markets and a recovering peso.

Zedillo also stressed that he is committed to “union freedom and the autonomy of labor organizations,” which have been controlled almost exclusively by the PRI.

Some analysts observed that by ceding the nation’s streets Monday, Zedillo and his labor loyalists succeeded in avoiding a bitter replay of the 1987 Labor Day parade. On that day, some union members enraged by Mexico’s last economic crisis broke ranks with their leadership and pelted the National Palace with Molotov cocktails.

Monday’s crowd hurled only insults and bottles at the colonial palace walls, which tower over the Zocalo. One group piled mounds of trash at the palace’s front door; others covered its walls with graffiti.

In a differing view about the importance of Monday’s events, some economic analysts concluded from the capital parade--an alphabet soup of groups with no apparent common front--that Zedillo will have little difficulty controlling a now-splintered, teetering labor movement.

Denise Dresser, an independent economist, contended that Mexico’s organized labor has been “atomized,” mainly by the PRI’s loss of patronage and jobs.

“Labor has been paying for the brunt of the crisis,” Dresser noted. “At this point, the key issue for them is just to keep jobs.”

That demand clearly was the loudest heard on the streets Monday. Some protesters angrily chanted for Zedillo’s resignation. Others scrawled the words “Trial for Salinas” on their faces--a message aimed at former President Carlos Salinas de Gortari, whom many Mexicans blame for the present economic crisis.

In Tijuana, a protest march organized for workers at maquiladoras --foreign-owned plants that take advantage of low-cost labor--drew a smaller-than-expected crowd of about 200.

“I’m here because of the wage problem,” said Patricia Jacinto, a worker at Rectificadores Internacionales, a U.S-owned electronics parts manufacturer. “With the devaluation, it’s not enough to pay the rent and food.”

Tijuana is the second-largest center of maquiladoras in terms of employees, and labor groups had expected May Day protests to attract up to 1,000 workers frustrated by the peso’s reduced buying power in a dollar-denominated border economy. But the morning march to Tijuana’s City Hall attracted mainly sympathizers with the Chiapas rebels, who have led a 16-month insurgency in the south.

Times staff writer Chris Kraul in Tijuana contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.