Ladies’ Man : At 72, Bill Blass is better--and more biting--than ever. Just ask the women who love his clothes and hang on his every fashion pronouncement.

- Share via

Designers are often accused of hating women. Hate is too strong a word. They do get weary, though.

Weary of women insisting that sleeves be installed in every dress. Weary of complaints that their creations are unsuitable for anyone under 30. Weary of their clients’ need for wardrobe approval from, of all people, other women.

It’s enough to make a grown man cry.

Not Bill Blass, though. Shoving his hands into his pockets after last week’s luncheon in his honor at Neiman Marcus in Beverly Hills, he dismisses his customers’ criticisms with an offhand remark, a raised eyebrow and a hint of disdain.

“ When, “ he grumbles, “will women learn not to ask other women’s opinions?”

The man who’s spent decades catering to society matrons knows the question is moot. Searching for something to wear to a summer wedding this day, Jane (Mrs. Michael D.) Eisner bows to her friend Nancy (Mrs. Thomas Reed Jr.) Vreeland’s judgment that a suit Eisner likes is, well, just not right.

“Don’t you think it’s too much pink ?” Vreeland asks Blass. “ Look at her, she’s already pink.”

And Eisner is, sort of, with pale hair and a pale complexion.

“What about navy?” Vreeland says.

“Well, yes,” Blass says, cautiously. “But the problem with navy, then, is the accessories. Navy shoes are a disaster. “

“What about black patent leather?” ventures a masochist.

“ What about it? “ Blass growls, eyebrow arched high.

*

Once, a Bill Blass appearance at Neiman Marcus would have been unheard of. In an arrangement common among designers and retailers, Blass agreed to appear at only one store, I. Magnin, when in Los Angeles. But ever since I. Magnin went under in December, the store’s resources--not to mention its customers--have been up for grabs.

The timing couldn’t be better. At 72, Blass is enjoying a sort of renaissance and, perhaps more satisfying, vindication. Grunge and street-influenced fashion have been eclipsed by the kind of pretty, conservative suits and dresses in lighthearted colors he’s been making all along. Sales of his last two collections--which critics have praised as the most youthful in years--jumped 30% over 1993.

The audience, too, once belonged to I. Magnin. The Blue Ribbon--a well-connected, well-dressed charity group--moved its annual luncheon to Neiman’s at the invitation of John Martens, vice president and general manager of the Beverly Hills store. It doesn’t require a leap of logic to understand that such an event could win Neiman’s some affluent new customers. (Neiman’s sold about $400,000 worth of Blass, according to the designer’s spokesperson, during the collection’s two days at the store.)

As the women line up on the store’s second floor for table assignments, one of the Blue Ribbon’s most high-profile members arrives. Barbara (Mrs. Marvin) Davis, in black-and-white Chanel, is whisked past the others and taken behind a partition that separates the private luncheon from the rest of the store.

What the uninvited miss is a show of Blass’ spring collection followed by generous servings of meatloaf made according to the designer’s own recipe.

“I would skip the eggs and the oil,” announces Nancy (Mrs. Alan W.) Livingston, studying the recipe on the back of the menu card. At another table, a woman brave enough to admit to owning ocelot and leopard coats eats a specially requested vegetarian meal.

Then, the event’s raison d’etre: Who will follow the designer back to the dressing rooms and how many $3,000 suits, $1,500 dresses and $5,000 evening gowns will they buy?

*

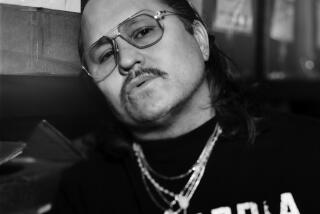

While assistants rush to-and-fro, helping customers with sizes and styles, Blass, wearing a chalk-striped charcoal suit and a few extra pounds, surveys pieces from his collection.

“For years my clothes were considered very wearable, and I used to think that was a terrible insult,” he says. “But there’s no point in making clothes nobody wears.”

A stream of women who may or may not buy something wait patiently to chat with the designer. It can safely be said that he shows no favoritism, treating all to equal doses of his renowned sarcasm.

Who can blame him? In a business that flits from one hot trend to the next, leaving the corpses of the slow-to-move in its mercurial wake, Blass’ George Sanders-esque cynicism seems as good a stance as any.

“I don’t believe in furs anymore,” he says, cutting off a woman who may have recalled the designer’s white mink peacoat, circa 1966.

“Fur is not for wearing.” A glance at the coat-check room testifies that not all agree.

Another admirer tries flattery.

“I have your pink suit and I get so many compliments when I wear it,” she says. But this only prompts a withering remark.

“Every woman in the world thinks pink is a color that looks good on her and her alone,” he says when she leaves.

His attention turns to a lovely model with porcelain skin, enormous ruby lips and hair that falls in blond, Veronica Lake waves. “I really like that girl. . . . I think I’ll use her in my next show.”

Emma, an L.A. model, has an English accent that’s not far off Blass’ barely perceptible drawl. Even though the designer was born in Fort Wayne, Ind., his wit, diction and wardrobe seem to come from a more gracious place and time. It’s an image that has served him well during his long and successful career, one that he forged as a sportswear designer and has continued as head of his own company, Bill Blass Ltd., begun in 1967.

“(Bill Blass’) super-civilized demeanor,” notes syndicated columnist Liz Smith in a column this week, “always makes one glad to be alive in what’s left of the 20th Century.”

Last year, the designer donated $10 million to the New York Public Library, a favorite cause among the East Coast society women who are his most loyal customers. At Neiman’s, Blass becomes his most animated when he talks about a recent New Yorker magazine profile of an idiosyncratic orchid collector.

In spite of his to-the-manner-born facade, Blass likes to make it known that he is a graduate of the school of hard knocks. He is visibly annoyed when a woman from the Otis College of Art and Design asks if the school might honor him at its annual gala.

“Good designers don’t go to school,” he bellows. “They should be knocking on doors. In this business, you learn by doing.”

(He does, however, think enough of his two honorary doctorate degrees--one from the Rhode Island School of Design, the other from Indiana University--to mention them in his press biography.)

“Did (Vreeland) try on the black dress?” Blass asks an assistant, referring to a strapless gown whose bodice is wrapped in taffeta that crosses the back and ties at the throat.

“She doesn’t like anything tight around her neck,” comes the whispered reply.

“That’s because there would be too many people who’d like to pull it really tight, “ Blass says with a laugh.

But it’s an affectionate remark. And ultimately, Blass’ favorite kind of woman seems to be one who doesn’t care what anybody thinks about how she looks or how she acts.

“I remember seeing C.Z. (Guest) once in Paris, in the ‘50s,” he says in the recently published book “The Power of Style” (Crown Publishers). “She came into the bar of the Ritz wearing a knee-length tweed skirt, a twin set and moccasins--and in a time when everyone else was tarted up in Dior’s new look, she stopped traffic.”