THE SUNDAY PROFILE : Voice of Change : UCI Prof. Joseph White’s Career Has Been a Potent Mix of Academics, Social Activism

In his townhouse a few miles from UC Irvine, Joseph White puts on a string quartet CD and begins to sift through mounds of material on a large, square coffee table. Classical music is his choice when studying or getting in the mood for his newfound practice of Zen meditation, but generally he turns to blues--”the gut-bucket, git-down Mississippi blues, the old-time stuff.”

Somewhere on the coffee table amid the mass of paperbacks, manuscripts and journals is a 1958 snapshot of Malcolm X, an acquaintance, White says, “before he went nationwide as the Malcolm X.”

Books are everywhere--on the couch, on tables, covering the four walls of his study. Near the front door, under the stairs, are yet more piles: cards and gifts from the recent party that celebrated White’s decades of teaching at UCI.

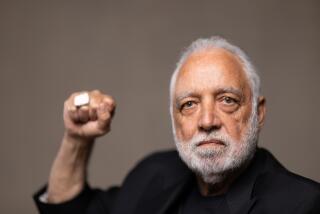

White’s countenance--he is of average build, not tall, thinnish hair tending to gray, with alert eyes behind glasses--speaks of patience and geniality. His laugh is irresistible--a tonsil-rattling mix of a croak and a snee-snee-snee. He chuckles as he locates the photo, recalling that although he and his cohorts at Michigan State University considered themselves progressive reformists, “Malcolm told us we were Uncle Toms in training. He used to come in and practice his speeches in my class.”

Next week White, 61, retires from UCI as professor of psychology and comparative culture. During a career that was a potent blend of scholarship and social activism, he crossed paths with Robert F. Kennedy, Eldridge Cleaver and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. He also rocked the psychology establishment on two fronts.

Along with a handful of other black psychologists, White in 1968 made public demands that more blacks be brought into the discipline. He also charged that traditional psychological theories were bankrupt when used to study black Americans, who have a unique ethos. His theories laid the groundwork for the growth of multicultural studies on campuses nationwide.

In the past two decades, however, it has been Joe White the educator who has impressed his students.

The grandson of a traveling Baptist evangelist, White inherited a lecture style that’s “better than theater,” according to one former student, who added that “even in three-hour classes, which can be sleepers, students would arrive 15 minutes early, so as not to miss anything.”

White’s diction is marked by smooth, regular downshifts into the vernacular to add emphasis; “Keep the faith” is his signature sign-off to classes.

To his students, White’s top value was as a mentor--a volunteer faculty counselor, confidant and guide. Dozens of black, white, Asian and Latino former students were among the 250 friends and colleagues at his surprise retirement party May 13.

“Joe is probably one of the most dynamic and charismatic professors I’ve ever encountered. He was an incredible mentor,” said Carly Flam, a former student who credits White with persuading her to get her master’s degree in counseling at Harvard. “He sparked my interest by bringing his experiences as an African American male to his teaching.”

Said Halford H. Fairchild, editor of the journal Psych Discourse: “I consider him my personal mentor, even though I never attended an institution where he taught. His reach is very broad. I call him mzee , which means ‘respected elder’ ” in Swahili.

White’s directorships, honors and fellowships fill eight resume pages. He played founding roles in Head Start, the Educational Opportunity Program and various anti-drug and anti-gang programs. A psychology teacher and practicing clinician for all of his 32-year career, he is an affiliate staff psychologist specializing in adolescent behavior at five Southern California hospitals.

Beginning in 1969, White taught psychology and directed the black culture program at Irvine. He became director of the African-American Studies program in 1991, an academic minor that currently has about 20 students.

“Looking at the field of psychology as it relates to African Americans, the title of ‘father of black psychology’ would have to go to Joe White. He brought the study of black psychology to the forefront,” said Robert Guthrie, author of “Even the Rat Was White,” a history of race relations in American science. (The late Charles Thomas of UC San Diego shares the title after serving as the first president of the Assn. of Black Psychologists.)

“The genius of Joe White was not just that he was champion for the (black psychology) movement but that he inspired so many students to be critical thinkers,” said Thomas A. Parham, a former student of White’s and now a professor of social science and director of UCI’s counseling center. “He was the first to call into question the Eurocentric paradigm for defining the lives of Afro-American people.”

*

From childhood, White was taught the importance of self-esteem. His strong-willed mother, Dorothy, had graduated at the top of her high school class and worked two jobs to support him and his siblings.

“The role models of my extended family also came into play,” White said. “I had an uncle who attended the University of Nebraska in the ‘30s, and another uncle was the only black in California to pass the bar in 1952.”

Born in Lincoln, Neb., in 1932, White at age 2 moved with his mother to Minneapolis after his parents separated. He was just 8 when he got a job at the downtown Curtis Hotel.

“The maitre d’ took a liking to me and gave me work polishing silver and running errands. It was work that I now realize really didn’t need to be done,” he said. “They let me work as a waiter when I was a teen-ager, and I made pretty good money and met all the important people in the Twin Cities.”

About that time, White’s older brother dropped out of high school. “My mother saw what was coming for me, so she yanked me out of that track and got me accepted at the Christian Brothers Catholic school across town. I was one of two blacks out of 800 students. She talked the brother superior into paying my tuition.”

Unbeknown to White, the school’s curriculum was college-prep, so after graduation he had fulfilled all the requirements for admission to the UC and Cal State systems. After working his way West as a waiter in the club car of a passenger train, he enrolled at San Francisco State College in 1950.

White earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in psychology, served a term in the Army and then looked for work, but without success. Frustrated, he turned to sympathetic counselors at San Francisco State, who told him that a Ph.D. was the only sure way for a black to get a good job.

The problem, White realized, would be to find a graduate school in psychology that would accept a black. Rather than go through the laborious process and expense of formally applying to colleges, White wrote brief letters to several programs. He asked whether there were openings for a student who had graduated with honors and who also happened to be black.

“Most schools sent me nasty replies, but worded diplomatically, saying things like, ‘Psychology is only for brilliant people. Maybe you should think about being a recreation director or social worker,’ ” White recalls. “But Michigan State accepted me, and so did (the University of) Colorado.”

*

It was after he earned his degree from Michigan State in 1962 that one of his career paths started to emerge.

When he arrived in Long Beach to begin his practice as one of only five black Americans in the nation with doctorates in clinical psychology, White became embarrassed and exasperated as landlords systematically refused him housing and office space.

“Even though I spent almost 18 months in the South as a soldier, I didn’t know how deep racism was in America till I got that Ph.D.,” White said, adding that the experience was particularly galling because “I had been trained all my life to believe in the performance aspect. I thought if you had enough (academic) tickets, that was all you had to do.”

In the years leading to his degree, White now realizes, the institutions of school and the military had shielded him from overt discrimination.

Recalling the letter-writing campaign that helped him start his doctoral program, White used a similar tactic to find adequate housing.

“I ran a classified ad in the Long Beach paper, saying, ‘Black couple with three small children seek large apartment.’ We got a few threatening phone calls. But then a guy called, and here’s what he did: We drove around till we found a house we both liked. Then he bought it and leased it to us. We were the only black family in the Lakewood area at that time. I made a public statement, and somebody came through.”

While a faculty member at Cal State Long Beach from 1962 to ‘68, White was frustrated by its low black enrollment. “Here we were, right on the edge of South-Central L.A., and out of 15,000 students we only had 65 blacks,” White recalls. “It didn’t make any sense.”

His solution: Use the special admissions option, normally used by the college to recruit top athletes who lacked academic standing, to enroll 68 blacks and Latinos. Eventually, with the legislative help of White’s friend, Assemblyman Willie Brown (D-San Francisco), the Educational Opportunity Program was expanded statewide, and White traveled to all 19 state college campuses in 1968.

During those years he was active in local housing issues with the Democratic Party in Long Beach, and in the spring of 1968 served as Long Beach campaign director for his “main man,” Robert F. Kennedy, in the presidential primary.

A few months after Kennedy was assassinated, the political turmoil continued for White when he found himself in the middle of the student strike at San Francisco State.

“It shut down the campus for 4 1/2 months. I was dean of undergraduate studies, and as the highest-ranking black, I was recruited into it and became a spokesman,” he said. “I had known the president of the university when I was an undergraduate, so I had a line to both him and the students.”

Eldridge Cleaver and other members of the Black Panthers, who lived in the same neighborhood as many of the striking students, made speeches and lent support during the strike, White said.

“The black students struck, and some white students and faculty struck with them. The kids wanted a full black studies department as an approved major. The protest to establish the legitimacy of black studies was solid; I endorsed that all the way. They were successful, and from there on came the ethnic studies at all campuses. But there came a point in time when the strike became an entity of its own rather than a means to an end.”

*

The late 1960s were years of crisis for White in other ways. In August, 1968, as the American Psychological Assn. was convening in San Francisco, he and 57 other black delegates were demanding reform within the organization.

In his 1984 book “The Psychology of Blacks,” White described the source of their frustration:

“Graduate schools in psychology were still turning out a combined national total of only three or four Black Ph.D.’s in psychology a year. . . . The grand total of (blacks) among the more than 10,000 members of the American Psychological Assn., psychology’s most prestigious organization, was less than 1%.”

On the convention’s third day, White and four other black psychologists held a rancorous meeting with the executive council. They demanded that more blacks be admitted to doctoral programs and wanted the association to make a statement in opposition to prevailing conclusions in psychology texts that blacks were an inferior race.

“It was a real intense meeting,” White recalled. “Some whites were called racist, and some on the council had been our own teachers. So it was almost a generational battle. Their notion was, why were we rejecting all they had taught us?

“What evolved from this was the APA forming a division of minority affairs, and we formed the Assn. of Black Psychologists. But we think there’s a lot left to be done.”

In district court a few years later, White and other black psychologists successfully challenged the legality of IQ tests that they said had caused a disproportionate percentage of black students to be labeled mentally retarded (in California in 1972, according to White, blacks comprised 9% of the student population but 25% of its retarded cases).

In White’s ground-breaking article, “Toward a Black Psychology,” published in Ebony magazine in 1970, he wrote that traditional psychology theories, which had been developed by white psychologists to explain white people, were inadequate to understand black lifestyles and unfairly led to blacks being defined as deviant or intellectually inferior to whites.

White disputed, for example, the widely held notion that black families are matriarchal. Rather, White wrote, the uncles, aunts, boyfriends, clergy and older siblings who participate in rearing a black child constitute a type of extended family. As such, they also prevent the child from developing rigid distinctions of male and female roles.

Other characteristics distinguishing blacks from whites were also ignored and thus contributed to skewed analyses, he says. These include an emphasis on collective, rather than individual, survival; respect for elders; an oral tradition; a spiritual nature, and a fluid, as opposed to a linear, perception of time.

Nearly a quarter-century later, black psychology is “a little beyond tolerance but not into total acceptability,” White says. “The strongest area of acceptability is in the practitioners. They require multiethnic psychology in the training. Without it, I don’t know how they could do marriage and family counseling or child development in California, which is 49% ethnic minority.”

A spokeswoman for the APA said the availability of strong minority candidates for graduate schools remains low.

“If you’re looking for a doctoral candidate and you want to pick from a pool, it’s not as diverse as it could be,” said Rhea Farberman, the spokeswoman. “We have internships and grant programs for ethnic minorities to increase the diversity in the candidate pool.”

The percentage of ethnic minority members in the 76,000-member APA has risen to 5%, says Bertha Holliday, director of the Office of Ethnic Minority Affairs. More than 20% of these minority members are from California, a fact that Holliday credits to White’s efforts in bringing blacks into the field.

*

For now, White says he’ll be using at least the first year of his retirement “to get my head straight” and take stock of his career. He wants to spend more time with his wife, Lois, an elementary school teacher, and keep in closer touch with daughters Lori, 36, a doctoral student at Stanford, Lynn, 34, a singer and paralegal in Los Angeles, and Lisa, 32, an assistant professor of geology at White’s alma mater in San Francisco.

He’ll also continue working on a book exploring the social psychology of black males, and another book on adult life transitions.

For 1995, White is considering a tempting offer: an endowed chair in psychology at the University of Nebraska.

Part of the offer’s appeal, White admits, is that it will bring him full-circle in a lifetime spent fighting racism.

For he would be returning in triumph not only to the city of his birth, but also to the very university where, during the Depression, his mother scrubbed floors at fraternity houses and his father, Joseph Sr., shined shoes at King’s Barber Shop three blocks away.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.