Uncommon Denominator : Mathematicians Gather in Honor of a Colleague Few Could Equal

At first it didn’t seem to add up.

Why would 200 of the world’s top mathematicians travel at their own expense from two dozen countries to camp out in a cramped dormitory east of Los Angeles and spend four days at a conference talking about differential equations?

Because Stavros Busenberg was their common denominator.

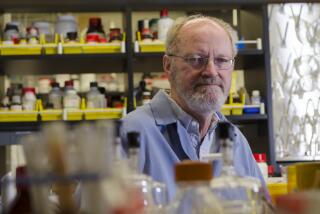

Busenberg was a mathematics professor at Harvey Mudd College in Claremont when he died a year ago of Lou Gehrig’s disease at age 51. But even in the arcane world of higher mathematics, he was unique.

“His reputation was enough to get me here,” said Eduardo Berretta, a professor at Urbino University in Italy who came to discuss mathematical models for drug administration that utilize Busenberg’s concepts.

Busenberg held a black belt in judo, but cultivated delicate wine grapes in his back yard. He could recite poetry in five languages and loved opera--but could drop everything for a strenuous bicycle ride or game of squash. He could chat as easily with overalls-clad workers on a noisy jet engine assembly line as with black-robed academicians cloistered in ivory towers.

In the classroom, he taught students that hard-core mathematics forms the basis of modern industry--and he backed that up by wrangling student sponsorships from local companies.

In the lab, he challenged colleagues to put their numbers to work for man, not machine. He devised ways of applying math to population and ecological problems. He was a trailblazer in mathematical biology--concocting numerical models that could forecast the spread of infectious diseases and the growth of cells.

Busenberg shared his work with anyone who wrote, called or messaged him by computer E-mail. He shared the glory, too: More than 30 co-authors are listed in papers and books that he wrote.

Mathematicians equated Stavros Busenberg with genius. And role model.

Maybe that’s why there wasn’t a single plastic pocket protector in sight Thursday as his friends gathered to discuss topics as diverse as “the one-dimensional hydrodynamic model for semiconductors” and “the probability of tumor cure after fractionated radiotherapy” and “roguing and replanting in orchards.”

“Everybody here was affected in one way or another by Stavros,” said Courtney Coleman, a Harvey Mudd math professor who worked for two decades with Busenberg.

“He was absolutely world-class,” said John Ockendon, a mathematician from Oxford University in England who praised Busenberg’s efforts to link the math classroom with American industry as pioneering.

Conference participants huddled in groups, some meeting colleagues they had corresponded with for years for the first time.

“I’m not surprised this many people are here,” said Carlos Castillo-Chavez, professor of biomathematics at Cornell University in New York. “Stavros was interested in everything.”

That showed at the lecture on the epidemiology of bovine tuberculosis delivered by Pauline van den Driessche, a professor at the University of Victoria in Canada. Not only was she incorporating his teachings, she told the crowd. She was using his lecture style as well.

The four-day International Conference on Differential Equations at Harvey Mudd College may become a biannual event, said Courtney Coleman, a math professor at the college.

Such sessions could help subtract from the myth of the mathematician as a nerd--an eccentric who spends a lifetime poring over numbers and rarely sees sunlight or ordinary people.

“It can be an isolating profession. A lot of mathematics is done in a room by yourself,” said Ann Sitomer, a graduate math student from Arizona State University. “If you’re by yourself for 20 years, you can come out strange. Some mathematicians seem to be on a different planet.”

Mathematicians need to become more visible as a group, said Fern Hunt, a researcher at the National Institute of Standards and Technology from Silver Spring, Md.

Those who struggled just to finish high school algebra should realize that math now plays a role in every facet of their lives, “except probably morals and issues of courage,” she said.

That’s something Stavros Busenberg deduced early on.