BOOK REVIEW / HISTORY : Disease ‘Lurks’ on Immigrants’ Path : SILENT TRAVELERS: Germs, Genes, and the Immigrant Menace <i> by Alan M. Kraut</i> ; Basic, $25, 369 pages

- Share via

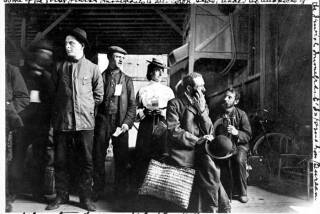

In science fiction, astronauts are disinfected to neutralize bacteria and “outside” diseases that might contaminate Earth or earthlings. In the American experience, we have disinfected immigrants, both literally and metaphorically, assuming that something disgusting from “out there” must be carried in the baggage of strangers.

Alan Kraut, a professor of history at American University, points out that Americans have always tended to see disease and degeneracy lurking in the bodies of newcomers.

His “Silent Travelers” is at once an object lesson in what we have done right and wrong in the past and a fascinating chronicle of America’s efforts, especially after the Civil War, to cope with immigrants whose labor we needed but whose foreignness we found frightening.

Nearly every national or ethnic group that has migrated to the United States, Kraut writes, was greeted by hostility and bureaucratic insensitivity. While it goes against the grain of our national self-image to dislike people because of their religion or their ideas, we felt justified in defending our families from disease.

Over the years, through waves of immigration, Americans have blamed the Irish for bringing cholera in the 19th Century, the Italians for bringing polio, the Chinese for carrying bubonic plague, the Jews for spreading tuberculosis and the Haitians for bringing AIDS.

The undesirables were defined, in part (quoting from the 1903 and 1917 editions of the “Book of Instructions for the Medical Inspection of Immigrants,” listed in Kraut’s appendixes) as “persons of constitutional psychopathic inferiority,” people with ringworm or “Loathsome Diseases”: venereal diseases, hernia, chronic arthritis, varicose veins and “defects of vision”--unaided vision of 20/70 or less.

This sieve wasn’t as fine as it might seem, because the brunt of carrying out these regulations fell to the shipping lines that profited from selling tickets to those wishing to immigrate to America. Still, the fear of rejection was real, as we see poignantly in Kraut’s interviews with immigrants who recall the fear and humiliation of the medical examination at Ellis Island.

Kraut follows these immigrants into the crowded tenements of New York, Boston and San Francisco, where public health workers used medicine to Americanize them.

Visiting nurses, for instance, instructed women in personal hygiene and nutrition, helping them in some ways but at the same time estranging them from their traditions.

He also describes how some immigrants fought back. Irish and Italian Catholics, for instance, opened their own hospitals to free themselves from Protestant proselytizing. Jews built medical centers where they could keep kosher and where, eventually, their children who studied medicine could find hospital affiliations when anti-Semitism barred them from older establishments.

Kraut includes stories of people such as the young Irish immigrant Mary Malone--known to legend as “Typhoid Mary”--who worked as a cook and spread deadly typhoid fever.

Mary was discovered by medical sleuthing, incarcerated by the New York Board of Health, then released on the grounds that her civil rights had been trampled after she promised to refrain from working as a cook. She broke her word, changed her name and infected another 20 people before she was found again. Mary was then incarcerated for the rest of her life.

Memories of Mary undoubtedly led in part to the repressive measures taken at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, in 1992, where Haitian refugees who tested positive for HIV were held in “the kind of indefinite detention usually reserved for spies and murderers.”

The association of disease with immigrants is only part of Kraut’s tale. He also describes the racist roots of the immigration bill of 1924 that kept Jewish refugees on the St. Louis from entering America in 1939.

A move to liberalize the bill was killed by the influence of people such as Laura Delano, the wife of the immigration commissioner and President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s cousin. Delano was overheard objecting to admitting “20,000 charming children (who would) all too soon grow into 20,000 ugly adults.”

Kraut introduces himself as the grandson of a tailor who made it through the immigrant health hoop to settle on New York’s Lower East Side. Defending the rights of all immigrants, he distinguishes the real public health problems posed by disease transmitters such as Mary Malone from the voices of prejudice that exploit our fear of disease for their propaganda war against America’s tradition of welcoming strangers.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.