JAZZ : Benny Green Stretches His Fingers : The 30-year-old piano phenom is disbanding his trio after its current tour, but it’s not because he’s dissatisfied with his bandmates

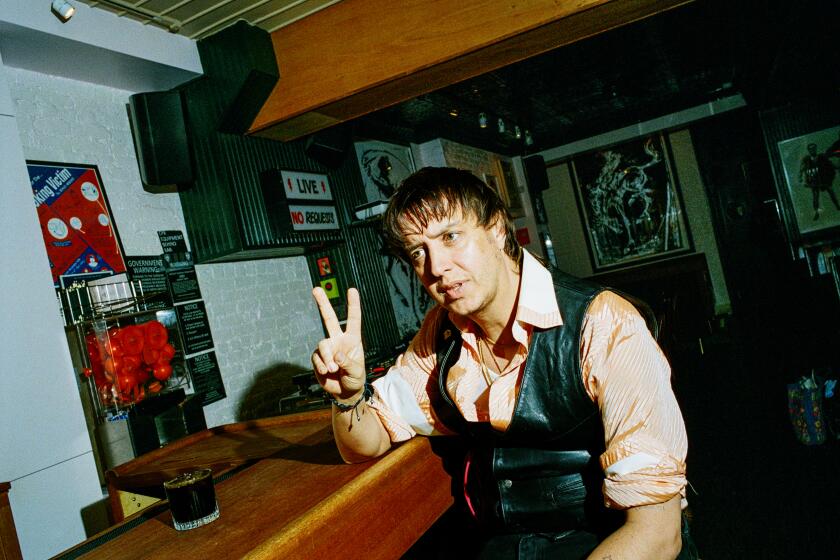

Benny Green, wearing one of his trademark dark green suits that complements his rust-colored hair and sets off his fair complexion, hunches over the piano in the dining room at Wheeler Hot Springs in Ojai. Performing with Ray Brown’s trio, the 30-year-old keyboard whiz is in the midst of a solo, delivering a long series of speeding lines that are dazzling in their complexity, their drive and swing, their consummate musicality. He finishes the improvisation, and for several moments there is no sound from the audience.

Brown, the legendary bassist, notes the quiet, and in an aside to the trio’s drummer, Jeff Hamilton, says, “I think he killed them.”

Then the crowd bursts out in enthusiastic applause, followed by cheers.

Green has been drawing these kinds of ovations for a decade as he’s toured the United States, Europe and Japan with singer Betty Carter, drummer Art Blakey, trumpeter Freddie Hubbard, bassist Brown and his own trio. Critical acclaim, too, has heralded him as one of the finest young pianists in jazz. Owen McNally of the Hartford Courant called him “certainly one of the most accessible and festive of today’s young pianists.” And The Times’ Leonard Feather said Green is a “technically brilliant and consistently creative soloist.”

While the influence of such artists as Oscar Peterson, Tommy Flanagan, Bobby Timmons and Bud Powell run through the slim, slight New York native’s playing style, Green is increasingly coming into his own. And in that process, he is living up to the potential as one of jazz’s major movers, a position seen for him by both critics and fans alike.

The chief characteristics of his approach to jazz are a singing improvisational quality, a sense of melodic grace and a rhythmic punch. He works with a light, dancing touch that can turn suddenly dark and his solos are permeated with an ardent bluesiness.

Green grew up in Berkeley. He began classical studies at age 7, and by 12 was playing jazz, urged on by his father, an amateur jazz saxophonist who taught Green tunes and exposed him to such jazz giants as Powell and Thelonious Monk. After studies with such Bay Area jazz pianists as Ed Kelly and Dick Whittington, Green moved to New York in 1983. There he worked with Carter for four years and with Blakey from 1987-89.

He met bass Wunderkind Christian McBride and drummer Carl Allen while working with trumpeter Freddie Hubbard, and with McBride and Allen formed a trio--a group that, he says now, has run its course. The trio will have its swan song during Green’s current two-month U.S. tour, which includes a free noontime concert at Santa Monica College on Jan. 11 and a six-night stand beginning that evening at Catalina Bar & Grill. (For the local engagements, Kenny Washington will replace Allen, who is staying in New York with his wife, who is due to give birth to their first child shortly.)

Green, who last year received Toronto’s prestigious Glenn Gould International Protoge Award, has made six albums as a leader: two for the Dutch Criss Cross label and four albums leading a trio for Blue Note Records--1990’s “Lineage” being his first, 1993’s “That’s Right!” being the most current. A recent conversation with Green began with a discussion of his work for Blue Note:

*

Question: Both “Lineage” and “That’s Right!” seem to have a more personal stance than “Greens” and “Testifyin’ “--two albums that seem to find you strongly in a blues frame of mind, playing tunes like “Down by the Riverside.”

Answer: I made “Lineage,” which featured bassist Ray Drummond and drummer Victor Lewis, just after I left Art Blakey, and, yes, there was something personal there in my music. I wasn’t so much thinking about projecting other pianists’ styles as putting something together that was my own. It was a fairly innocent period. But I hadn’t gotten the grasp of the components that go into leading a band. I didn’t know Ray and Victor that well. We just went into the studio and didn’t have that close rapport as human beings that is essential. It was more just a professional arrangement. The guys treated my music with respect, but I felt a little intimidated.

*

Q: That “human” element was in “Greens,” which featured Christian and Carl?

A: Yes. Freddie had us open up the shows as a trio, play a tune or two, and it felt really good. There was a lot of freshness and humor there that made me want to pursue that trio.

“Testifyin’ ” (which was recorded live at New York’s Village Vanguard) documented our working band, and by then, in 1992, we were functioning as one. At the same time, I was really taken by the way pianists like Gene Harris and Ramsey Lewis could grab hold of an audience. There was a sense with them of a sermon taking place between the musicians and the audience, the bandstand being the pulpit and the audience being the congregation. I wanted to tap into that kind of power. I think that in imposing that demand on myself, I may have momentarily inhibited the whole expanse of my musical potential.

But with “That’s Right!” I changed the style a bit, moved in the direction of playing more original music, extending my voice as a pianist through compositions as well as playing. I also wanted to document the sense of freedom and spirit that Christian, Carl and I share.

*

Q: Why are you breaking up the band?

A: It’s time to let Christian and Carl pursue other avenues. They’re so busy. It will be best for everyone. Maybe a year ago, I was more frightened to make a change, but now I welcome it. I want to get some guys I can spend time rehearsing with, and really work on advancing my repertoire. It’s one thing to snag guys like Christian and Carl for the occasional trio gig, but we used to spend a lot of quality time together, and we don’t now (due to our busy schedules) and that’s what I’m looking for.

*

Q: What are the main rewards from playing with Ray Brown?

A: How nurturing the musical relationship is for me. First of all, he’s the only veteran musician that I have played with who is completely open, willing and caring enough to take all the time necessary to help me with any musical question. And he won’t just answer the question. He’ll take some time and think about it, ending up giving me useful and practical advice. It’s the most precious thing in our friendship.

*

Q: What did you get from your experience with Art Blakey?

A: Art told me to go out and play with some attitude. The audience is not interested in self doubt. People have come to have a good time, they want you to have a good time. Jazz is an art form, but we’re also here to entertain people, to make people happy, to make people feel, period.

Another part of his jazz message was that you should become a bandleader yourself, that leading brings something from within. I really blossomed with him, and I might not have, had it not been for that association.

*

Q: What goes through your head when you’re soloing?

A: I try to sing a song from within and try to translate that to the piano. It’s still that way. Ideally, you’re playing what you feel. You want to react to the moment, come more from your heart than a strictly intellectual place. The technical knowledge that we accumulate is a means, like the vocabulary of a musical sentence, but it still comes back to the feeling that’s in your heart. It’s a relationship between yourself and your instrument and you really want to form a closer bond.

*

Q: What’s a good way to form this bond?

A: There are several components. It has to begin with yourself as a person . . . the kind of values you have, the amount of care and respect you have for others. Your whole compassion and feeling toward humanity inevitably comes through in music whether you’re trying to or not.

Still, there’s no shortcut and substitute for being with your instrument. That doesn’t include just spending time sitting at the piano. It also involves thinking about the instrument when you’re physically away from it, going about your everyday life. Thinking about what it represents, the beautiful sounds it’s capable of achieving, those you are aware of and those yet to be discovered.

*

Q: Who are you listening to these days?

A: Oscar Peterson, Art Tatum, Hank Jones, though, more and more, I go for long periods without listening to records. I have been recording myself on gigs and when I hear things happen in live performance that surprise me, that are unlike anything I’ve heard, I want to examine that. It’s really time now to be getting in touch with my own language, putting together my own vocabulary. Still, as I’ve felt in past, I don’t want to be far from music that is touching me. I just want to personalize what I have ingested--want that to be a continuation of the same heritage that’s inspired me.

*

Q: What’s a typical day like when you’re at home in New York?

A: Basically, my time is spent practicing, eating, sleeping, performing, listening and resting. At home, I wake up when I want, play when I want, sleep when I want. That can really change dramatically from day to day. Today, I got up at 8:30 a.m., practiced an hour or so. Now I’m talking to you. Tonight, I might still be up at 4. Sometimes, instead of sleeping eight hours, I may take two or three hourlong naps.

*

Q: What about being on the road? What’s that like?

A: When we’re traveling, sleep is sometimes hard to get. I might come back from a gig, and have only two or three hours before we have to leave for the next job. So instead of trying to sleep for those few hours, I may stay up, maybe not eat, drink juice, have fruit, and then go straight to the next gig. There’s a certain kind of nice, alert energy that comes with that.

*

Q: The feeling you get from playing music must be extraordinary.

A: I definitely wouldn’t exchange what I do for any other alternative. Sometimes I’ll play things that I haven’t heard anyone else do, that I feel are totally spontaneous. A moment like that is a little glimpse into something that is supremely beautiful, and gives me a little reminder, or a sign, that what I’m doing is of some spiritual merit. That gives me gratitude and appreciation--makes me so grateful that I don’t have a job where my heart isn’t in it. I have to remind myself that this spiritual direction is really a kind of blessing, to be afforded the opportunity of doing something which is enriching and rewarding to my soul, is kind of unique, unique to all musicians, but not something to be taken for granted.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.