Documentary Immortalizes Enemy of TV : Video: An Orange County native profiles naturalist author Edward Abbey, who once showed his disdain for television by shooting a set.

- Share via

“There are two kinds of poisonous lizards out West,” Edward Abbey once wrote. “Gila monsters and real estate speculators.”

In a writing style that has been compared to both Thoreau and Twain, Abbey aimed barbs at any number of folks, from Western cattlemen grazing their herds on public land (“nothing more than welfare parasites”) to fellow “nature” writers who were, to Abbey’s mind, too mystically inclined (“gushing about finding God in every bush”).

“I sat on a rock in New Mexico once, trying to have a vision,” he told The Times in 1988, a year before his death. “The only vision I had was of baked chicken.”

To fans of such books as “Desert Solitaire” and “The Monkey Wrench Gang,” the self-described “agrarian anarchist” was a spirited defender of the Western wilderness; to his detractors, he was a crank or worse, maybe even dangerous. The controversial Earth First! environmental movement was inspired by “The Monkey Wrench Gang,” and Abbey remains something of its spiritual father.

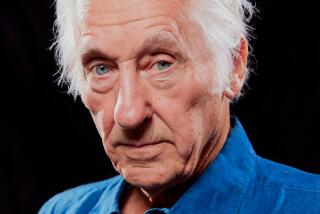

Television was one of Abbey’s favorite targets, figuratively and literally--one of the most widely published photos of the author in his later years shows him leaning on a shotgun, grinning widely, a shattered TV set at his feet. It is at least a little ironic, then, to find that Abbey’s life has now been encapsulated for the small screen.

“Edward Abbey: A Voice in the Wilderness” is a one-hour documentary recently released to the home-video market. Video clips of interviews with Abbey, sound recordings of the author reading from his works, and interviews with family and friends help illustrate the evolution of Abbey’s life and art.

The documentary was written and directed by Eric Temple, a graduate of Corona del Mar High School who was working at a public-television station in Phoenix when he first met Abbey (who lived outside Tucson).

“I had been a fan, and I used my position at the TV station to meet him,” Temple said in a telephone interview from his current home in Bethesda, Md. “The first thing he did was offer me, a 21-year-old kid, a cigar.”

Temple taped an interview with the author for a half-hour program called “Edward Abbey’s Road,” which aired on many PBS stations in 1983.

The Abbey that Temple met differed from what he expected. For all that his sometimes cantankerous polemics and grizzled visage might suggest, Abbey in person was surprisingly soft-spoken and thoughtful, although he didn’t hesitate to share an opinion.

Temple met the author a few more times before Abbey died at 62 of “internal bleeding caused by a circulatory disorder,” as the newspapers reported. Huge public wakes were held in the red-rock country of the Southwest that Abbey spent his life exploring, defending and celebrating.

About two years after Abbey died, Temple called the author’s widow, Clarke Abbey (the last of his five wives), with the idea of doing a video project about his life.

“Initially, I wasn’t going to do a complete biography, but more of a tribute,” Temple said. “My first idea was to do audio of him reading, with pictures of the places he wrote about.”

At Clarke Abbey’s urging, Temple began to expand his concept of the project, and soon he found himself interviewing a score of Abbey’s friends and relations.

Some were models for characters in Abbey’s novels, such as Doug Peacock, the inspiration for George Washington Hayduke in “The Monkey Wrench Gang” and the posthumously published sequel, “Hayduke Lives!”

In the original 1975 comic novel, a loose band of Western malcontents engages in escalating acts of “ecotage,” first burning down highway billboards and eventually plotting to blow up the Glen Canyon Dam, a longtime target of Abbey’s animus.

In one of the funniest segments in Temple’s video, some of Abbey’s friends squirm when asked how much of the book was based on real incidents. Peacock wonders aloud about how the statute of limitations applies before declining to get specific.

“Edward Abbey: A Voice in the Wilderness” gives the broad outlines of the author’s life, stopping to linger at some of its more interesting crossroads.

Abbey was born on a farm in Home, Penn., and after an Army stint hitchhiked West in 1946. He studied English and philosophy at the University of New Mexico and started writing novels, while supporting himself at a series of odd jobs.

His second novel, “The Brave Cowboy,” was made into a 1962 movie with Kirk Douglas (retitled “Lonely Are the Brave”) that Douglas has called his favorite. Abbey continued to struggle as a writer, however, until the 1968 publication of “Desert Solitaire.”

A collection of essays loosely tied around two seasons he spent working as a ranger in Arches National Monument (now Arches National Park) in Utah, “Desert Solitaire” put all of Abbey’s gifts on display.

He described the austere beauty of the canyon country with a lyrical gift to rival Muir or Thoreau; he told hilarious stories; he attacked such scourges as “Industrial Tourism” with a wit and rage that helped put a spark of real passion into the burgeoning environmental movement.

As Temple’s video illustrates, Abbey was surprisingly ambivalent about the book. Considering himself a novelist first, he had to be prodded by his publisher to release “Desert Solitaire.” Publicly, at least, he professed to be surprised by its popularity, but he came to be known at least as well for his essays as for his novels.

The publication of “The Monkey Wrench Gang” cemented Abbey’s cult following and his reputation as an environmental iconoclast. If the book left any doubt, Abbey said in subsequent interviews that he had no qualms about attacks on property (but not on human life) in the defense of wilderness.

Abbey’s legend continued to grow, and in a 1988 interview he said he was, if anything, getting more radical as he got older. But his health was a problem all through the ‘80s, and in 1988 he published “The Fool’s Progress,” whose dying protagonist drives back to his Appalachian birthplace one last time, just as Abbey did.

Temple tells the story of Abbey’s life mostly through the remembrances of friends and relatives, and through taped interviews with Abbey himself. Once he started interviewing people, he said, others heard of the project and asked to be included. They volunteered photographs, manuscripts and other research material.

“Everyone was extremely cooperative,” Temple said. He spent a month with his family on the road in a motor home, traveling Utah, New Mexico and Arizona for interviews and location shots. “It felt like were kind of walking with Abbey, like he was there.”

Temple said he was a university student in Flagstaff when he read his first Abbey book, “The Monkey Wrench Gang.”

The project took about two years, and Temple finished editing last March 14, the fourth anniversary of Abbey’s death. It recently won first place documentary and best of show in the 1993 Utah Short Film and Video Festival, and will be shown at the Mill Valley Film Festival in October.

Temple is trying to sell rights for broadcast of the show to cable television but in the meantime has started independently marketing videos to the home market, advertising in outdoor and environmental magazines and selling it through independent bookstores.

The video cost Temple money and time, but he hopes to recoup the investment and feels fortunate to have done the film, his first independent project. “I was sorry when it was over . . . (but) I was also extremely glad to be the one to do his life.”

* “Edward Abbey: A Voice in the Wilderness” retails for $24.95 and is available through Canyon Productions, Bethesda, Md. (800) 644-4747.

Edward Abbey’s Elegy to Canyon Country

“Do not jump into your automobile next June and rush out to the canyon country hoping to see some of that which I have attempted to evoke in these pages. In the first place, you can’t see anything from a car; you’ve got to get out of the goddamned contraption and walk, better yet crawl, on hands and knees, over the sandstone and through the thornbush and cactus. When traces of blood begin to mark your trail, you’ll see something, maybe. Probably not. In the second place, most of what I write about in this book is already gone or going under fast. This is not a travel guide but an elegy. A memorial. You’re holding a tombstone in your hands. A bloody rock. Don’t drop it on your foot--throw it at something big and glassy. What do you have to lose?”

--Edward Abbey, from his 1968 book, “Desert Solitaire.”

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.