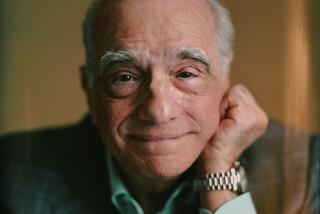

‘Innocence’ Is at Stake in Columbia’s Gamble : Movies: Studio has a lot invested in Martin Scorsese’s lavish period piece that cost at least four times more than ‘Howards End.’

- Share via

When the long-anticipated “The Age of Innocence” opens in 16 cities on Sept. 17, it is considered almost certain to appeal to moviegoers who have lapped up “Howards End” and other filmed classics by the producer-director team of Ismail Merchant and James Ivory.

But though “Innocence” may seem to have the ingredients of a Merchant-Ivory film--it is a period piece based on Edith Wharton’s Pulitzer Prize-winning 1920 novel--the team that brought two books by Henry James to the screen had nothing to do with it.

A lavish production costing at least four times that of “Howards End,” “Innocence” is not an art-house film but a major studio release directed by Martin Scorsese and starring Daniel Day-Lewis and Michelle Pfeiffer. Set in New York City during the 1870s, the story centers on an extramarital romance between an aristocratic lawyer trapped in the conventions of his time and an expatriate countess who has violated the oppressive rules of a clannish society.

Columbia Pictures hopes the anticipated favorable reviews in the mainstream press plus the marquee names will bring in a far larger audience than such upscale “frock dramas” normally attract. But, the studio, which acquired the project after another studio abandoned it as too expensive, has a lot at risk.

“Howards End,” for example, grossed $26 million domestically--plenty for a film that cost only $8 million to make--but far less than Columbia needs to take in to break even on “Innocence.” The studio insists the film cost slightly more than $30 million. Other industry observers have estimated the film cost more than $40 million, but producer Barbara DeFina, denying these rumors, said Day-Lewis and Pfeiffer relinquished part of their fees to keep down costs.

The studio is also banking on strong international interest in “The Age of Innocence,” which opened the Venice Film Festival Tuesday.

A faithful adaptation of the book, the sumptuously designed movie poses several challenges for the studio. The subtle and gradually unfolding drama proceeds slowly and requires audiences to plunge themselves into another epoch, when divorce could stigmatize a woman to the point of ruin. The ending is not likely to leave moviegoers whistling. At 2 hours, 13 minutes, the film is lengthier than most, although not so long as to reduce the number of showings per day.

Mixed early reviews in trade publications predicted that the film’s appeal will be decidedly limited. But Bert Manzari, head film buyer for the Landmark theater chain, disagreed. “This is Scorsese, for crying out loud,” he said. “This is not a struggling art film.”

Five years in development and initially budgeted at $20 million, the project eventually became so costly that 20th Century Fox dropped plans to make it in late 1991 just as Scorsese was scheduled to go into pre-production. “We were looking forward to it but the price became a little too rich for our blood,” said former Fox President Roger Birnbaum.

Instead, it became the first film greenlighted by the then newly installed Columbia Chairman Mark Canton. Fortunately for Scorsese, Canton was willing to accede to the director’s demands to re-create the characters’ world in meticulous detail, jacking up the film’s price.

Columbia announced last October that the movie, originally scheduled as a Christmas, 1992, release, would be delayed almost a year. The studio cited two reasons: Scorsese’s father was ill (he died last month), necessitating a slower editing pace; and with Columbia’s “A Few Good Men” expected to be a strong Oscar contender, the studio did not want to put another picture into competition with it.

In retrospect, said Sid Ganis, Columbia’s president for worldwide marketing and distribution, “what really was important was that Marty complete the film the way he wanted to. That definitely took time.”

Much of the spending went into set design and costumes. So intent was Scorsese on period authenticity that Robin Standefer, the movie’s visual research consultant, hunted down the historical models for the characters in the novel so that the director could have the paintings in their private collections copied. (Scorsese got so much help from the New York Historical Society that the film’s Sept. 13 premiere is being held as a benefit for that organization.)

Why was it necessary to go to such lengths? “It was important that the audience feel as though they were living in that age,” DeFina said. “That helps you understand their emotional life. Everything was beautiful and lush and yet very restrictive.”

Scorsese also found the studio supportive in other ways. While it is commonplace in Hollywood to fiddle with endings, this one was sacrosanct, DeFina said. “Going in we said, ‘That’s it. It’s not changing.’ That was always a given,” she recalled. “There are people who have seen the movie who said, ‘God, I hoped it would be different.’ But the ending is very truthful . . . not just because it’s in the book, but that’s the way the character would behave.”

Scorsese himself is playing a major role in Columbia’s marketing campaign, even though his movie at first glance seems a big stretch for a director better known for capturing the grittier, more violent side of New York life. According to DeFina, however, the elegant and sedate film is just as violent as “GoodFellas” and “Mean Streets.” “He sees the violence as being emotional and psychological,” the producer said. “It’s brutal at times.”

In marketing the movie, Columbia has been emphasizing the timeless aspects of the story, just as Warner Bros. did in selling the hit 1988 period film “Dangerous Liaisons,” also starring Pfeiffer, which grossed $32.8 million domestically and did very good business overseas. (That movie, though, was far more overtly sexual and was based on a well-known play.)

One 30-second spot, for example, enumerates “Innocence’s” themes in a litany of nouns: desire, suspicion, betrayal, lies, rage, passion and heart. Another series of ads gets more personal, asking: “If what you desire most is the one thing you cannot have, which would you betray: your whole world or your heart?” The studio sees its core audience as adult women.

As in the case of art movies, the studio, which has held numerous small screenings for the press, plans to rely on word of mouth to build interest. The film will open slowly--in only one theater in 13 of the initial 16 cities. But the distribution pace will quickly accelerate so that the film is in 800 to 1,000 theaters by Oct. 1, two weeks after it opens. An extensive advertising campaign will include a heavier-than-customary use of a longer, more costlier 60-second spot. “We don’t want to rush our message to the potential moviegoer,” said Ganis.

Because of the popularity of Pfeiffer and Day-Lewis (who is seen as especially hot after “The Last of the Mohicans”), the movie has already generated plenty of free publicity, including cover stories in such national magazines as Premiere, Entertainment Weekly and Vanity Fair. A new mass-market paperback of “The Age of Innocence” had a first printing of 250,000 copies and is already a bestseller in Washington, D.C., a spokeswoman for Macmillan, the publisher, said.

In addition, the studio produced a half-hour film on the making of the movie that will air on HBO seven times during the month of September.

Then, there is always the international market. “This is definitely the type of picture Europeans go for,” said a marketing executive at another studio, who did not wish to comment publicly on a competitor’s movie. “Longer, slower pictures do better with those audiences, as long as they perceive it as something that could be cinematically great.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.