PROFILE : It’s the Right Fit for KNJO’s Harvey Kern : The once-a-week radio personality designs his on-air show for comfort, the familiar, the pridefully suburban.

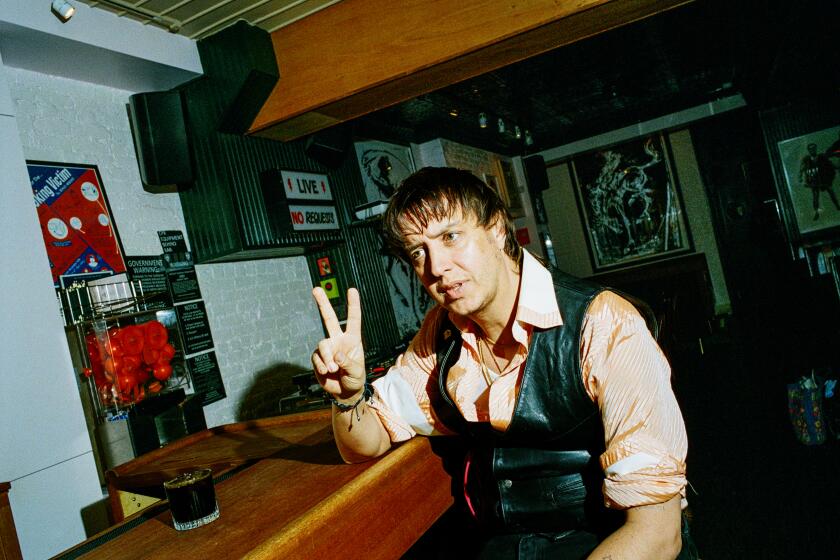

Harvey Kern, the bespectacled, towering length of him looking as professorial as anyone possibly could, is surprised at the reaction people take when they hear that he goes on the radio to issue “pet reports.”

“When I tell people about this, they say, ‘Come on, give me a break,’ ” Kern says. “But listeners are very serious about pet reports. You name it, we’ve tracked it on the air: somebody’s lost pet boa, lost pet tortoise, an unknown horse seen roaming through somebody’s back yard, a skunk someone was keeping that got away.”

Kern pauses a moment, leaning forward in his easy chair to emphasize his point:

“You can’t imagine the level of emotion. I’ve had people call in to the station, in tears, to say: ‘Thank you; I’ve found my dog.’ Well, right there you have a listener for life.”

Harvey Kern would like it that way, thank you very much.

Kern appears each Sunday morning from 6 to noon on KNJO (92.7 FM) radio, which blankets the Conejo Valley from a transmitter atop Ventu Peak and reaches points as far north as Ojai. Kern’s is the unmistakably gentle, deep voice that, besides issuing pet reports, announces sports, news, weather, commercials, civic promotions and “soft hits” by such agreeably mainstream voices as Neil Diamond, Melissa Manchester and Whitney Houston.

His is not a show to jostle; rather, it’s designed for comfort, the familiar, the pridefully suburban.

This month marks Kern’s 15th year as a Sunday personality in these parts. And he couldn’t be happier about it. “I just love it,” he says. “It’s special. It’s me and the listener.”

But the radio isn’t the only place you’ve likely run across him.

*

In February, from deep East Los Angeles, Kern appeared on television nationwide to announce that the mammoth County-USC Medical Center was secure, that patients were being cared for despite the shooting hours earlier of three physicians and the taking of hostages.

Kern’s day job, as any true on-air devotee would call it, is a consuming one: director of public affairs for the hospital, the largest acute-care facility in the United States. In addition to his media-management and marketing duties, Kern represents the center’s interests to politicians in Washington, coordinates activities of the LAC-USC Medical Foundation and otherwise acts as executive assistant to the center’s director.

To do this job from his quiet home in Oak Park, Kern is on the road each morning at 6 and usually, barring emergencies or special broadcasts such as the triumphant release of burn victim Sammy Jones, home about 7. Add to this a 28-year stint one night a week as a graduate instructor of health sciences at Cal State Northridge--a job that ended only this year, with budget cutbacks.

It all makes for a long day, a long week. Kern’s been at it, in varying capacities within the Los Angeles County Department of Health Services, for 29 years, early on as a restaurant health inspector in the San Fernando Valley. Rat control officer. Nursing home licensing and hospital accreditation coordinator. Swine flu program administrator.

While he enjoys his current high-powered job, Kern, now 50, admits that he contemplates retiring in a few years.

Among other things, he hopes that it will give him more air time.

For Harvey Kern can’t avoid the simple truth. Radio is his thing, the one activity in which, he says, “so many things come together.”

*

He offers, with some self-effacement, the following confession:

“I don’t know where it came from. I just always wanted to do radio. People even remarked about it to me. When I was a little kid, I would walk around the house with an extension cord, talking into it like a microphone.”

To talk to Kern is to stand beneath a waterfall of words: He is loquacious and highly articulate, serving up narratives embedded with parallel lines of story development. Stop him midstream to ask “Why radio?” and he whirls up a word eddy.

“My wife of 29 years, Reva, is an artist. My daughters, Ilana and Carla, had always had their own activities going. And, in the late 1970s, particularly in 1978, I was facing some worry around possible layoffs relating to Proposition 13. I was working long hours. Simply, I didn’t have a stress reliever, something I could call my own. I enrolled in radio school.”

Pause.

The man in chinos, plaid shirt and black leather walking shoes pops a huge smile.

“I loved it. I ate it up. I would have stayed all night after class if I could.”

Kern’s first on-air opportunity was as a one-day substitute for an ailing disc jockey. In a few months, announcer Bill Jackson left the station and Kern was called to see if he wanted the Sunday morning gig.

The fit was right from the start.

Kern, of course, would gather experience in multiple venues. His children were enrolled in the then-fledgling Oak Park schools, and high school football games were without an announcer, without a press box.

Undaunted, Kern climbed atop the school’s roof and called the plays through an electronic bullhorn. He would, as the years passed, receive a plaque marking his service as “The Voice of the (Oak Park) Eagles.” But it lent him an even more valuable legitimacy with, of all people, his daughters.

“Working at KNJO was not exactly something your kids would run around bragging about,” he says. “But the football players liked me, and so then I became cool to my daughters.”

*

Kern is realistic about the part-time gig for which he has a full-time passion.

“Look, I know I’m not James Earl Jones,” he says. “That voice. When he says, ‘This is CNN,’ I mean WOW. You know that that’s James Earl Jones.

“For that matter, neither am I Ernie Andrews, who does the Ford advertisements, or Norman Rose, the voice of Hallmark.”

But then Kern isn’t trying to be. While he has, in his commercial work at KNJO, been the voice behind ads for Pacific Central Mortgage, Courtesy Chevrolet and (as a talking bear) for the Ford dealership in Simi Valley, Kern plainly enjoys the personal connection he feels with listeners.

“From the very beginning,” he says, “I found that when I went in (to the broadcasting studio), I wasn’t worrying about work or anything else. It was me and the listener, that’s all.”

Such an intimacy is only reinforced when Kern goes on location to announce live from such venues as Conejo Valley Days. “That’s very special,” he says. “You get to see people who know you from years of listening. It’s that tie-in between the community and KNJO that makes it special.”

While 15 years of Sundays is impressive in its own right, in a communications company, it’s epic. Kern has survived four station owners, five station managers, four station locations and numerous format changes--formats that, in Kern’s words, went from “very close to elevator music” to “up” rock (as distinguished from metal) to “adult contemporary” to the current theme of “soft hits.”

Understated. Intimate. Aware of the listener’s concerns, whether it’s about local news or a lost pet.

It’s material for what Kern calls “theater of the mind,” a radio universe in which the message, while cameraless, becomes “visual” to the listener--something more powerful than TV.

With that, it’s easy to see why Harvey Kern, toiling in the thick of things all week in L. A., gets up at 4:30 every Sunday morning to head for the mike.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.