Southwest Museum’s Director Was Savior, Not Thief, Jury Is Told

- Share via

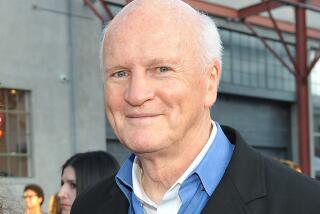

When Patrick Houlihan was director of the Southwest Museum, he took numerous valuable objects from its collection and traded them without authorization, his lawyer said in court Monday.

Houlihan, who headed the Los Angeles museum from 1981 to 1987, also altered documents to cover up what he did, the lawyer admitted in opening arguments at Houlihan’s theft and embezzlement trial.

But Houlihan took those actions, his lawyer said, not to ravage the museum but to save it.

He said Houlihan secretly traded the objects, some appraised at several hundred thousand dollars, to enhance the museum’s collection and to help pay for renovations.

“The charges that are called embezzlement are in fact things Dr. Houlihan did to help that museum,” lawyer George Buehler told the jury in Superior Court.

However, Deputy Dist. Atty. Alexis de la Garza described Houlihan’s actions as “not only improper but illegal,” whatever the intent. And she told jurors she would prove that Houlihan used the money he gained from the sale of one object to buy a home in Arizona.

De la Garza further charged that some of the items Houlihan took were on long-term loan and not really owned by the museum. “That did not really matter to the defendant,” she said.

If Houlihan, one of the country’s most prominent museum administrators in the field of American Indian arts and artifacts, is convicted of all the charges against him, he could be imprisoned for up to seven years.

The 15 objects he is alleged to have taken--including textiles, paintings and kachina dolls--were discovered missing during an exhaustive inventory in 1989. They were recovered during a three-year investigation by the FBI.

Houlihan is currently director of the Millicent Rogers Museum in Taos, N.M. The president of the board of directors of that museum was in court Monday to show support for the defendant.

The prosecution and the defense agree that Houlihan dramatically revitalized the venerable Southwest Museum, located in the Mt. Washington area.

De la Garza said that Houlihan was driven to bring the museum into the modern age: “He saw a lot of things he wanted to have happen and he wanted them to happen right then and there.” Buehler said his client was frustrated by what he believed was the board of trustees’ inability to raise the funds he needed. So he removed objects from the storage area and traded them for pieces he thought the museum needed.

Houlihan hid the transactions from the board, Buehler said, because he was afraid they would want him to drastically raid the collection and sell off objects to cover the institution’s debts.

De la Garza characterized the transactions as more akin to outright sales. One of her witnesses is expected to be Jerrold Collings, an Arizona rancher who was a dealer in Southwest artifacts in the 1980s. During grand jury proceedings, Collings testified that he had bought the poncho that De la Garza said gave Houlihan the funds to purchase his Arizona home.

Buehler countered that the money Houlihan got from Collings was an unsecured loan. He said that Collings made up the story about the poncho to please the FBI.

“It was only when he was being threatened with prosecution that he changed his story,” Buehler said, pointing out that Collings has received immunity in return for his testimony.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.