Canada Rejects Unity Program in Referendum

- Share via

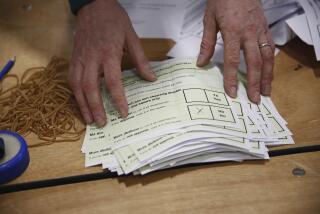

MONTREAL — Canadians overwhelmingly rejected a sweeping package of constitutional amendments that were put to a rare national referendum Monday.

The amendments were written by Canada’s office-holding elite in an effort to keep united this fractious, three-ocean country, the world’s largest political entity after Russia.

But the unambiguous “no” will certainly scuttle the entire package and open a new and uncertain chapter in Canadian history.

The package was rejected by voters in six of Canada’s 10 provinces, in some cases by wide margins. In British Columbia, for instance, about two-thirds of the voters said “no” to the amendments. And the key French-speaking province of Quebec also voted “no.”

Quebec’s vote was closely watched because the amendments were written in large part to satisfy Quebec French-speakers. Quebec has never ratified the Canadian constitution, in the belief that it fails to protect the province’s minority French language and culture.

Some observers had been warning as the referendum approached that a “no” vote would set in motion events that would lead to the eventual breakup of Canada along linguistic lines. Other analysts, however, have called for calm, saying a “no” would merely mean business as usual in America’s northern neighbor.

The sharply contrasting interpretations could be clearly heard here in Montreal, Canada’s largest truly bilingual city, where the “yes” and “no” committees each rented trendy nightclubs to stage their referendum-night activities.

At the “yes” headquarters, Quebec’s premier, Robert Bourassa, downplayed the impact of the balloting, saying that while the voters had rejected the amendments, that doesn’t mean that they rejected Canada. The wan-looking Bourassa, a longstanding federalist, said he had no intention of changing his government’s position on Quebec’s place in the confederation.

“We cannot imagine that the disintegration of this federation would be advantageous to Quebec,” Bourassa told the applauding crowd of “yes” supporters. “We believe that we will be able to build Quebec within Canada.”

But just five blocks down the street, at the stylishly dilapidated nightclub rented by the “no” committee, separatist leader and parliamentarian Lucien Bouchard suggested that Quebec’s “no” vote was the first step toward independence for Quebec.

“We have two paths ahead of us--renewed federalism, and sovereignty,” said Bouchard, as “no” supporters cheered and waved the blue-and-white Quebec provincial flag in the tiers of balconies above. “As far as I’m concerned, the converging point (for those two paths) will be sovereignty for Quebec.”

Bouchard, who leads the small but important Bloc Quebecois in the House of Commons, went on to hint at his political strategy over the coming days and weeks. He said that Monday’s referendum shows that Canada’s federal politicians lack legitimacy, and he urged that Prime Minister Brian Mulroney call a national election soon.

Bouchard, who used to be a member of Mulroney’s Cabinet but defected to form the Bloc Quebecois and work for Quebec sovereignty, seemed to be suggesting that he will try to convince other members of Mulroney’s Progressive Conservative Party to jump ship and the sovereignty camp. If Bouchard succeeds at this, he could whittle away Mulroney’s majority in the House of Commons, and indeed force an election at a time when Mulroney’s standing in the polls is painfully low.

In a brief nationally televised midnight address from Ottawa, Mulroney made no mention of electoral politics. He merely said that the heavy voter turnout showed that Canadians have faith in the democratic process and that he now intends to focus on economic issues.

In Quebec, voters rejected the amendments in the belief that they do not do enough to empower the province to protect its French heritage.

Elsewhere in Canada, however, voters rebelled against the amendments in large measure because they thought the package offered too much to Quebec. British Columbians, in particular, were outraged at a provision that would have guaranteed Quebec 25% representation in the House of Commons, even if its population slipped below 25% of the Canadian total.

The stark difference between Quebec’s “no” and that of English-speaking Canada make the chances of a French-English reconciliation anytime soon seem remote. Politicians, stunned by the unequivocal response of the voters, were quick to state that they have no intention of returning to the constitutional amendment-drafting table anytime soon.

“I believe that we should hold the constitution in abeyance,” said New Brunswick Premier Frank McKenna. “Stop talking about it. Talk about the things that unite us.”

If the constitutional dialogue in Canada ceases now, though, it will be a bitter disappointment for Canada’s Indians and Inuit, as the Eskimos prefer to be called. Many of them believed that a provision of the package that would have enshrined their “inherent right” to self-government was the best deal Canada had offered them in the 125-year history of confederation.

“You’ve kept apartheid alive in Canada, that’s what you’ve done,” an embittered Ron George, head of the Native Council of Canada, told voters in a televised address.

Highlights of Canada’s Referendum

The question put to Canadian voters was this: Do you agree that the constitution of Canada should be renewed on the basis of the agreement reached on Aug. 28, 1992?

AGREEMENT’S KEY POINTS

Quebec is recognized as a distinct society; at least three of nine seats on the Supreme Court are to come from Quebec.

Culture is entrenched as a provincial jurisdiction, but the federal government continues to control national institutions such as the Canadian Broadcasting Corp.

A new Senate with six senators from each province and one from each territory is created.

Ontario, Quebec, British Columbia and Alberta get extra seats in the House of Commons. Quebec is permanently guaranteed 25% of the seats in the Commons.

The inherent right to aboriginal self-government is recognized.

Existing national programs such as Medicare are protected. In new cost-sharing programs, provinces can run their own with federal money if they meet national objectives.

If provinces want, they can control federal money spent on housing, recreation, forestry, mining, tourism, urban affairs and job training.

If provinces want, they can take control of immigration and regional development.

Source: Times Wire Services

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.