PERSONAL PERSPECTIVE : I Briefed Bush on the Arms-for-Hostages Deal

- Share via

Soon after the Iran affair evolved into the Iran-Contra scandal in December, 1986, George Bush told America he was aware of the Iran initiative and supported the President’s decision to secure the release of American hostages. The essence of Ronald Reagan’s decision was that the U.S. government would secretly sell weapons to the Iranian government in exchange for Tehran using its power and influence to free Americans held by Iranian-backed terrorists in Lebanon. This would lead to a high-level dialogue between American and Iranian leaders that would enhance the U.S. strategic position in the Gulf.

In 1986, I participated in several meetings with then-Vice President Bush at which the core elements of the Iran initiative were discussed. There was no ambiguity about the fact that arms sales to Iran were a prerequisite for the release of the American hostages. After Atty. Gen. Edwin Meese III announced that profits from the sales had been diverted to the Contras, Reagan directed everyone involved to cooperate fully with all duly appointed investigative bodies.

I was interviewed by the FBI and the Independent Counsel. I testified under oath before two Senate select committees, the Tower Commission, a House select committee and the grand jury. In my testimony, I reported on Bush’s involvement, but none of these bodies, nor the media, paid much attention to the vice president.

The role of a vice president in formulating and conducting national security and foreign policy varies with every administration. But under Reagan, Bush continuously participated in the policy-making process and was assigned many diplomatic responsibilities. He chaired the Counter-Terrorism Task Force and the South Florida Drug Task Force; he secretly negotiated with foreign heads of state and led numerous delegations to inaugurals and funerals of foreign leaders.

During the Reagan Administration, certain interagency committees regularly met to assess U.S. policies throughout the world. The staff of the National Security Council was responsible for convening the meetings. It was standard-operating procedure to invite Bush.

Typically, Bush’s national-security adviser or a member of his staff would participate in the meetings, thus providing the vice president with an opportunity to contribute to the policy-making process at the staff level, as well as at the decision-making level when issues were formally presented to the President. Bush’s input was usually communicated through his staff to the national-security staff at the working level or in private to the President or the national-security adviser. During the five years I served on the national-security staff, the office of the vice president actively participated in every interagency group I chaired or worked on. Bush’s views were always taken into account.

The meetings with Bush involved issues ranging from the Iraq-Iran War, crisis management, Lebanon, the Arab-Israel conflict, arms sales, terrorism, Libya and the Persian Gulf, to his frequent meetings with foreign dignitaries. We met privately for in-depth briefings and discussions of the Middle East. It was a pleasure to talk with Bush because of his knowledge, experience and genuine interest in foreign affairs.

During the many Middle East crises, Bush chaired the Special Situation Group, the government’s most senior crisis-management body. At the meetings I attended, Bush always conducted the discussions with professionalism and relish. He was in the foreign-policy loop on every Middle East issue of which I was aware.

But a funny thing happened to many of the senior officials of the Reagan Administration after the Iran-Contra scandal erupted. A sudden epidemic of premature Alzheimer’s disease spread through the offices of the President, vice president and the departments of State and Defense, infecting virtually everyone. No one could remember anything, except that the all-powerful national-security staff had somehow been running the world behind everyone’s backs for much of the preceding years.

Cabinet officers who had stridently opposed the Iran initiative, while refusing to resign in protest, shirked any responsibility and publicly distanced themselves from the President. They and their immediate subordinates feigned ignorance and placed all responsibility for the policy on the shoulders of the national-security staff. Secretaries Caspar W. Weinberger and George P. Shultz, as well as key members of their staffs, were clearly in the arms-for-hostages loop. Chief of Staff Donald T. Regan also knew what was going on.

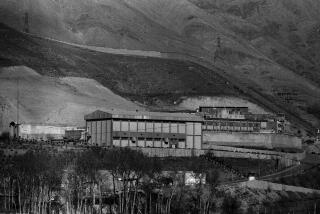

For years, a photograph has hung on my office wall. It was taken in the Oval Office the morning I and others returned from Tehran in May, 1986. It shows our briefing of Reagan, Bush and Regan on the mission’s results. No one present was out of the loop. But like all the afflicted principals, Bush’s level of knowledge declined as the scandal unfolded.

Bush could never have had any doubt about the attitudes of Shultz and Weinberger toward the Administration’s Middle East policies. Although the two men were generally at odds on every Middle East issue, they were united in their opposition to the Iran initiative. The importance Reagan attached to finding a way to free the hostages, however, was equally obvious. Indeed, Bush was offering his help at least as late as July, 1986, when I participated in a meeting with him on the Iran initiative.

By December, 1987, Bush was lamenting that he never really heard Shultz and Weinberger express their opposition “clearly,” because the “key” players weren’t ever called together. The decisions were, instead, made at a “lower level” and weren’t reviewed. It can be argued that Oliver L. North kept many operational details of the Iran initiative to himself. But it can’t be seriously disputed that Bush was definitely in the loop on the Iran initiative.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.