Positively, Abbott Can Pitch

It was easy for Jim Abbott to be left-handed. All he had was a left hand.

You might say he was born left-handed. But not in the sense a Lefty Grove was. Abbott was not issued the requisite right hand at birth. Left-handedness usually has to do with hemispheres of the brain or a reverse cortex of something. Jim’s had to do with necessity.

What wasn’t easy for Jim Abbott to be was a ballplayer. Ordinarily, you need all your limbs--to say nothing of fingers--for that.

That’s why James Anthony Abbott is, by all odds, the most extraordinary story in athletics today--or maybe ever. Look, it’s easy for Nolan Ryan or Bret Saberhagen to go 12-6 and 13-8, respectively, in ’91 and strike out 203 and 136 along the way. They have all the standard equipment. For Jim Abbott to go 18-11 and strike out 158 is something no one ever expected to see.

They applauded when little Jimmy Abbott went out for athletics. They thought it was cute, heart-warming. It was commendable he could try to overcome or ignore an apparent impediment like that. Commendable but not logical. Hardly anyone thought he could persevere beyond Little League or Pop Warner football. He would have to get a job where hands were not a prerequisite.

You can conceivably play tennis with one hand. In this era of scoop layups and one-handed jump shots, you could conceivably play basketball. Michael Jordan hasn’t put up a two-handed shot in decades, and you only need one hand to dribble. Football is possible--if you’re a lineman.

But baseball would seem to be a two-handed game. A one-armed outfielder, Pete Gray, briefly played the game during World War II with the St. Louis Browns. He actually got 51 hits and made 162 putouts, but his wartime appearance was widely perceived to be merely a stunt by owner Bill Veeck.

Abbott never intended to be anybody’s stunt. He never faced discouragement, only skepticism. “I went out for sports because that’s what kids did in Flint, Mich.,” he recalled as he sat in a locker room in Anaheim Stadium the other night. “I played baseball in the summer, basketball in the winter. People were supportive. There were always skeptics, but they kept it to themselves.”

Abbott paid no attention. He was too busy working on his curveball. The cynics were unconvinced.

There are theologians who contend that God never gives you more adversity than you can handle. Or then waits to see if you can handle it. Abbott was the one tested.

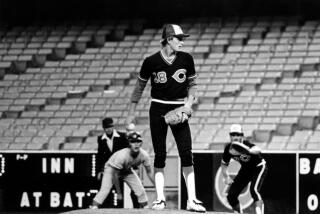

He passed with flying strikeouts. Jim Abbott didn’t brood about his infirmity, he ignored it. He chose the position most suited to his particular circumstance--pitcher--and set about to becoming the best he could.

That was very good, indeed. His fastball hummed, his curveball swerved. The grumblers were unconvinced. “Wait’ll they start bunting on him,” they predicted sourly.

Abbott perfected switching a glove from his right wrist to his hand. He pounced on bunts, and the tactic backfired on the team at bat. “I look on a bunt as an out,” he says candidly. “I’m glad to see ‘em.” He adds: “Oh, sure, sometimes, still, when a guy tries to drag a bunt past me along then first and third base line, I feel he’s testing me. But a lot of the time it’s a guy who would try a drag bunt on Roger Clemens.”

He concentrated on positives. Good enough to get a baseball scholarship to Michigan, he breezed through the collegians, put up a 26-8 lifetime record with 186 strikeouts in 234 innings.

He had actually been drafted (by Toronto) in high school. But it wasn’t exactly a ringing endorsement: 36th round.

He won the gold medal game in the ’88 Olympics, beating Japan, 5-3, and won the Sullivan Award as amateur athlete of the year, beating out David Robinson (basketball), Karch Kiraly (volleyball) and Greg Foster (hurdling) and joining such greats as Bill Walton, Mark Spitz, Carl Lewis, Edwin Moses and Bobby Jones.

Finally, the Angels drafted him. During the first round.

Everybody hoped. Few really believed.

He made the opening day roster. He lost his first two games, 7-0 and 5-0, which proved prophetic. Abbott finished the season 12-12. By May of that year (1989), he was beating Clemens and shutting out the Boston Red Sox in Fenway Park. In his 12 losses, his team was outscored, 65-23, and scored one run or zero runs six times.

It was an omen. The next year, in his 14 losses, his team scored 15 runs for him. Last year, in his 11 losses, the Angels scored 20 runs.

This year, it’s more of same. His record is 2-6, but his earned-run-average is 2.77. That’s Cy Young Award stuff.

He never spent a day in the minor leagues. He joins another left-hander, one Sandy Koufax, in that impressive category.

His 18-11 record last year, his lifetime 40-37 up to this year, stamp him as not only a major league pitcher but a star. He finished third in the Cy Young Award voting last year.

But that’s for sliders and curves. For inspiration, he should be given the Congressional Medal of Honor. He is the only reason I have ever had to be glad about the designated-hitter rule.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.