‘Heat Wave’ Over Arctic Slows Ozone Depletion : Stratosphere: Development prevented a ‘hole’ like that over the Antarctic, scientists say.

- Share via

WASHINGTON — An abrupt warming of the stratosphere over the Arctic in late January slowed the depletion of protective ozone, preventing the development of a northern ozone hole like that over the Antarctic, scientists reported Thursday.

The temperature increase, coming extraordinarily early in the season, apparently halted formation of microscopic ice particles that create polar clouds. Without the clouds that trap ozone-destroying chemicals, chlorine levels declined.

Chlorine and bromine--the chemicals produced by the families of refrigerants, solvents and fire-fighting compounds called CFCs, HCFCs and halons--destroy ozone molecules in the stratosphere.

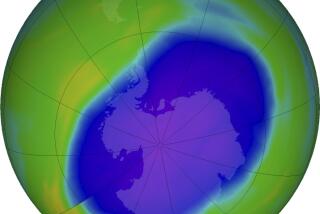

In the Antarctic, the depletion is so severe that it is popularly referred to as an ozone hole. But there is mounting evidence that the thinning of the layer extends even to the mid-latitudes, allowing increased levels of ultraviolet radiation to reach the Earth.

Preliminary results from Arctic observations by satellite and aircraft last February so concerned the Bush Administration that it moved up its target date for phasing out CFCs from the year 2000 to 1995.

The 74 countries that have signed the so-called Montreal Protocols mandating an end to CFC use by 2000 are to update the agreements later this year in Copenhagen, Denmark, specifically concerned with whether to banish the less-damaging HCFCs and halons.

Robert Watson of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, one of the country’s leading ozone depletion experts, said Thursday that he believes the protocols should be toughened.

Although the Arctic winter did not produce an ozone hole as scientists had feared, flights over the Far North through the winter showed ozone depletion of as much as 20% at altitudes ranging from 24 to 32 miles.

Participants in the project had been concerned that serious depletion across Europe and North America was developing early this year when NASA’s Upper Atmosphere Research Satellite detected spreading chlorine monoxide, the most destructive form of chlorine, over Greenland, northern Europe, Russia and the North Atlantic.

In December and early January, the ozone-killing chemical was increasing by 1% a day, said Joe Waters of Caltech’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. But after a month-long hiatus in the observations, scientists found that mid-February levels had decreased--a trend that continued through March.

Though the ozone destruction did not reach the level feared, Waters said the findings nevertheless reveal that conditions in the upper atmosphere are in “a very delicate balance.”

“With so much chlorine in the stratosphere, a slight temperature difference can make an enormous difference in the potential for ozone depletion,” he said.

The health consequences of reduced stratospheric ozone--increased incidence of skin cancer and potential harm to the body’s immune system--has catapulted concern over the damage into the forefront of global environmental issues.

F. Sherwood Rowland, a UC Irvine atmospheric chemist who discovered CFCs’ role in ozone depletion, said the latest research “confirms that you do lose ozone over the Northern Hemisphere and suggests the mechanism involved is very similar to that which works over the Antarctic.”

Times staff writer Maura Dolan in Los Angeles contributed to this story.