Right Place at the Right Time : World: Hoping to help Russia embrace its future, a D.C. deal-maker knows how to pick winners--including Boris Yeltsin.

- Share via

WASHINGTON — Allen Weinstein was jarred awake by the shrill sound of a ringing telephone.

When he answered it, all he heard was a crackling, like a bad connection originating far away. It was what?--4 a.m.? 4:30?--and he couldn’t get back to sleep. He decided to get the paper, have some breakfast and head for the office.

It was about 7 when he arrived, and already there were two faxes. Strange, he thought, who could be sending messages this early?

As soon as he read them, he knew.

“It is military coup,” said the first fax bluntly. “Tanks are everywhere.”

“Tanks are around the council,” ran the second. “Yeltsin denounces the coup. . . . Yeltsin tried to contact Gorbachev and failed.”

It was Aug. 19, and a right-wing coup had been launched against Soviet President Mikhail S. Gorbachev and the newly elected democratic government of the Russian Federation. Russian President Boris K. Yeltsin and his ministers were holed up in the “Moscow White House,” as the Russian government headquarters is known, cut off from almost all communication. But they still had use of a fax machine.

And of all the fax machines in all the offices in all the buildings in Washington, they chose to communicate through Allen Weinstein’s.

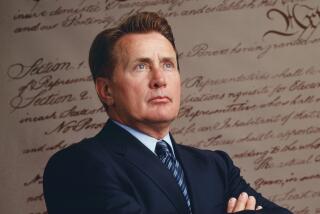

He has been called the “Mr. Fixit” of Russia, a name he absolutely loathes. “I don’t fix anything,” he says almost petulantly, and in that respect, he’s correct.

The 55-year-old Weinstein runs the Center for Democracy, a nonprofit foundation created to promote the democratic process around the world. Since its founding in 1984, the center has operated in a relatively low-key way: sponsoring conferences, running election observation teams. Its strengths have been in networking and facilitating.

But in 1991, thanks to a combination of networking success, luck, hard work and Weinstein’s personal chutzpah, the center jumped into the headlines in a big way.

In essence, Weinstein and the center became Boris Yeltsin’s advance team in America. The center sponsored Yeltsin’s trip to the United States last June. It has been intimately involved with the environmental policy side of the Russian government and, even though it is not a relief organization, it has acted as a go-between for American farmers distributing food to the Russian people.

From educational and legal reform to advice on privatization and setting up a business clearinghouse for Americans interested in investing in Russia, Weinstein and his small full-time staff of 15 have their fingers in a lot of pies.

“It always helps to be in the right place at the right time,” says Weinstein, “but we’re not in the business of exporting democracy. We’re trying to facilitate a process that is very indigenous. What we’ve done is simply respond to requests.”

The Center for Democracy isn’t the only organization heavily involved in the long-term Russian make-over; there are hundreds of such groups. But Weinstein’s may be the most publicized.

Weinstein has been the subject of a two-page interview in Time. In addition to the “Mr. Fixit” appellation it hung on him, the Washington Post has referred to him as “the dean of the new overt operatives,” a network of above-ground activists who have, over 10 years, “been changing the rules of international politics.”

The fax incident raised Weinstein’s stock and visibility. It also has raised the level of back-biting against him inside the Beltway.

In the competitive world of Washington think tanks and foundations, some people--who would not speak for attribution--say they see Weinstein as a shameless self-promoter and an arrogant publicity seeker who talks a good game but rarely accomplishes anything. He’s been accused of being a bit too close to the Bush Administration.

Talk to those he’s worked with, however, and the story is entirely different. Take Tom Loughmiller, a key figure in a consortium of Idaho growers that is sending 100 tons of dehydrated potatoes to Russia this month. The center is helping expedite the shipment and will distribute 60% of it to schools and orphanages. “They were very anxious to help us,” Loughmiller says of his dealings with the center. “They’ve been very flexible and helpful.”

Adds Charles Bonser of Indiana University’s Institute for Development Strategies, who has met with Weinstein and his staff regarding the establishment of an American-style university in Russia: “He’s bright, energetic and very aggressive. I think he’s been adept at meeting people, connecting them with other people, trying to see needs. That’s the kind of role he played for us.”

“I don’t doubt that envy exists,” says Weinstein.

“This is kind of a ‘When did you stop beating your wife?’ question.”

He was not necessarily raised to play this role. Born in the Bronx to Jewish immigrant parents who owned a deli-restaurant, Weinstein attended City College and Yale, where he earned a doctorate in American studies.

He taught history at Smith College for 15 years and wrote a controversial book about the Alger Hiss spy case. He also taught at Boston University and Georgetown, has worked as an editorial writer for the Washington Post and hosted a PBS program, “Inside Washington.”

But he was always, he says, drawn toward public affairs, where he could really make a difference. Weinstein is not particularly emotional--he has a good sense of humor yet tends to be afflicted with that rampant Washington disease, terminal seriousness--but he exhibits real warmth and passion when discussing why he was drawn to the public world.

“I come from that Depression-World War II generation,” he says. “I don’t want to romanticize it, but there was a sense, particularly after the war, of opportunity, of things opening up. Culturally, historically, I am predisposed toward optimism, a sense of change.”

In 1984 he became president of the Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions in Santa Barbara, with a dream of creating a bi-coastal think tank. But his directors had a vision that was “more cerebral and phlegmatic than mine,” so he resigned and established the Center for Democracy.

Weinstein believes the reason behind the center’s success is relatively simple: It comes from the relationships established among groups of people with a similar democratic purpose.

For instance, Weinstein and his staff already knew every current president of Central America before he or she became president. The same holds true for a key figures from all over the world.

It was networking that brought the center and Yeltsin together. Weinstein became interested in Yeltsin in 1990, while attending a conference of Eastern European and Russian reform politicians in what was then Leningrad. The politicos were discussing Yeltsin in a favorable way, and Weinstein became intrigued.

Several months later, a Yeltsin environmental aide came to Washington and worked for several months out of the center’s offices. Weinstein sent word that he wanted to sponsor a Yeltsin trip to America and went to Moscow to make preparations.

“The importance of that early meeting was just listening to him,” says Weinstein. “I was impressed by his general aura and quality. . . . The negative stories I had read (allegations of drinking and boorishness by Yeltsin) weren’t borne out by what I saw.”

So a working relationship was born. Under center sponsorship, Yeltsin came to the United States last June and gave what Weinstein calls “an extraordinarily polished performance.”

Yeltsin paid back the favor by using the center as a conduit for faxed messages during the August coup--13 in four days, all of which were hurriedly translated and sent to the White House, the State Department and the press.

Once the coup was crushed, Weinstein flew into Russia and, after conferring with local officials, began prioritizing needs. Basic assistance came first. Attempts to encourage Russian farmers to send more goods to market were next. Eight months later the center is, in conjunction with a number of organizations, involved in a wide range of projects:

* Ongoing emergency aid projects, like the potato shipment.

* The development of an American university, as well as a project to train Russian instructors in business education.

* A teleconference allowing Russians and Americans to discuss economic reform measures and foreign investment.

* Reformation of the legal system, including judicial retraining.

* Partnered with the Discovery Channel, the production of a series of educational TV programs on democratic institutions and free-market economics.

It hasn’t been easy. Weinstein and his staff have had to deal with a stultifying bureaucracy that tends to swallow problems rather than handle them.

“Every question is a problem,” he says. “Imagine a situation in which the (United States) had to deal with its revolution, creating its Constitution, creating virtually all of its law codes fresh, creating a new economic system and fighting its secessionist struggles, all in the midst of the worst economic catastrophe in its history. These folks are confronting that every day and, in effect, are forced to develop the outlines of this in 200 days.”

So far, so good, as Weinstein sees it. The future of the Commonwealth of Independent States may be shaky, but that’s primarily because it was “designed as a bridge institution.”

At the same time, Weinstein believes that Yeltsin’s legitimacy as a democratically elected leader means he has survived the winter and now has about eight months--until the next winter--to “engage in fundamental reform.”

More important, in his mind, is what the United States intends to do about building the democratic process in the former Soviet Union.

America seems to be undergoing a sort of historical version of future shock over the end of the Cold War: We know it’s over but haven’t come to terms with it yet. Because of this, says Weinstein, “there is still no firm commitment regarding what the U.S. intends to do as a country to be fully engaged in this process.”

Weinstein is so far ahead of the historical curve that he’s already wondering about the role of the intelligence community. With that in mind, he has organized an international conference on the subject this week in Bulgaria. It probably marks the first time that KGB and CIA operatives will break bread in public.

This button-down guy is not afraid to let his passions show. He really believes in positive change, in man’s search for a better order. But as a historian, he also knows that the world moves in very strange ways.

“I believe in very few historical laws,” he says, a small, almost impish grin creeping across his face. “Except the law of unintended consequences; confusion, not conspiracy.

“Oh, yes, and that other iron law of history--one thing leads to another.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.