Cystic Fibrosis Cure Seen in Gene Therapy

Federal researchers have developed a bold new form of “Trojan horse” gene therapy for cystic fibrosis that they say could cure the disease, eliminating the characteristic lung congestion and infections and greatly prolonging patients’ life spans.

Cystic fibrosis, the most common lethal genetic defect in the United States, impairs lung function, rendering the victim more susceptible to potentially fatal infections. The new treatment could be tested in humans within a year.

The researchers say they have inserted a healthy copy of the gene that is defective in cystic fibrosis into a common cold virus that has been defanged so that it no longer produces colds. The advance is reported today in the journal Cell by a team headed by molecular biologist Ronald G. Crystal of the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute

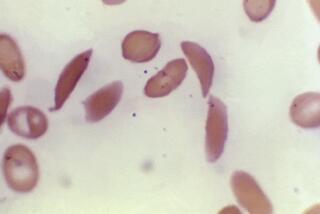

When they sprayed this “Trojan horse” virus into the lungs of rats, it carried the gene inside lung cells, which began producing the healthy protein. The researchers are testing the safety of the virus in larger animals.

The treatment would most likely have to be repeated many times over a patient’s life, but “it is a cure,” Crystal said Thursday.

“This is the next logical step in developing gene therapy for cystic fibrosis, and it’s a very important one,” said biochemist Ronald J. Beall, executive vice president of the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. “This is a potential therapy that could restore these people to normal health, and that’s what we want for our CF patients.”

About 12 million Americans carry the defective gene that causes cystic fibrosis, and one in every 1,800 children suffers from the disease. It is characterized by the buildup of a thick mucus in the lungs that impairs breathing and leaves the victims unusually susceptible to respiratory infections. The disease also affects the pancreas in about 75% of victims, blocking secretion of enzymes necessary for digesting and absorbing fats in the diet.

Most victims succumb to repeated infections, and earlier in this century virtually all died in their first year of life. But the development of improved antibiotics to control the infections has extended the median life span to 27, and many patients now live into their 30s and 40s.

There has been no therapy for the disease itself, but two new drugs called Amiloride and DNase, now undergoing clinical trials in humans, have shown promising results. Both dilute mucus in the lungs so that it is less likely to harbor infectious agents. Both drugs would probably work well in combination with the new therapy, Beall said.

Researchers have held out hope for gene therapy for cystic fibrosis since the defective gene that causes it was discovered in 1989. But it has been clear that the task would require an unusual way to approach the problem.

In conventional gene therapy, cells are removed from the body, genetically engineered to alter their characteristics and then reimplanted.

That approach is not practical in the lungs because the intricate structure of the lungs prevents the removal of cells.

A cold virus called an adenovirus is ideal for the job because it attacks only lung cells, passing through the outer membranes of the cells and releasing its DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid, the genetic blueprint of life) inside them. The virus could thus be an effective “Trojan horse” that would sneak the gene into the cells in the same fashion that, according to legend, Greek warriors were sneaked into the ancient city of Troy in a large wooden horse.

Crystal and his colleagues at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore and Transgene SA in Strasburg, France, selected one of the many adenoviruses that infect humans and removed the genes that produce the symptoms of a cold.

In place of the deleted genes, they inserted the healthy form of the cystic fibrosis gene. Then they used an aerosol of the virus to expose it to the lungs of rats. They were able to demonstrate that the human protein was produced in the animals’ lung in concentrations higher than those found in healthy humans and that it persisted in the cells for at least six weeks. The scientists said these levels would be sufficient to cure the disease.

Since no animals develop cystic fibrosis, however, the researchers were not able to show that the gene therapy actually eliminates the disease. But they are confident that it will do so in human experiments because they have already found that the virus “cures” human cystic fibrosis cells grown in the laboratory.

“I have no doubt that if we were to (use the altered virus) now in a person with cystic fibrosis that we could . . . reverse the abnormalities in the lung,” Crystal told the Associated Press.

But first, they must demonstrate its safety in animals. They are studying safety in rodents and other small animals, Crystal said, and within a few weeks will begin testing in monkeys. If it proves safe there, they will be able to begin testing in humans, perhaps in as little as a year.

Among researchers’ concerns are whether the altered virus can produce side effects, whether it might combine with other adenoviruses and become infectious and whether the animals will develop immunity to the virus. “Our studies so far suggest that these are not problems,” Crystal said, but the virus has not been administered repeatedly to the animals, as would be required in human therapy.