Paternity Case Ruling Stuns Mother, Gives Father Hope : Family law: Although he has no biological connection to the boy who calls him ‘Daddy,’ Larry McLinden has a chance of winning custody.

- Share via

After Larry McLinden’s girlfriend told him she was pregnant, the Canoga Park couple shopped for furniture for the baby’s room, attended Lamaze training together and were the center of attention at the requisite baby showers and family gatherings.

McLinden was in the delivery room with Karen Hamilton through 12 hours of labor before she gave birth to a healthy baby boy on July 1, 1987. The boy was baptized Larry McLinden Jr., and in the first album of baby photos his mother even noted his likeness to Larry Sr. On another page, a family tree showed Larry Sr. as the boy’s father.

But McLinden was not Larry Jr.’s father--at least not until last week.

In an unusual ruling that observers say could set a California precedent in paternity law, a judge declared McLinden the father of the 4 1/2-year-old boy even though he has no biological connection to the child and was never married to his mother.

Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Dana Senit Henry granted McLinden all the rights of a natural parent, ruling that separating McLinden from the boy he helped raise could severely traumatize the child.

The ruling, which concluded a three-week trial on McLinden’s paternity suit, will give McLinden equal standing with the boy’s mother when the court determines custody next month.

The mother, who is now married to another man and uses the name Munyer, finds the possibility of losing custody of her boy stunning.

“I can’t believe this is what the law in California means--that a mother could lose her baby to someone who is not even the father,” Munyer said in an interview last week. “I just can’t understand it.”

McLinden said he sees the ruling as a great stride toward bringing the courts into step with society.

“I was faced with the complete loss of all rights to my son, complete separation from the boy I helped raise,” he said. “I think the courts and Legislature have to catch up to what is happening in our society. Maybe this is the beginning of realizing that there needs to be some modification of parenting laws.”

McLinden, an investment banker, and Munyer, a secretary, met at a nightclub in the San Fernando Valley and shared an on-and-off relationship beginning in 1982. They agree on few details of their relationship.

During the paternity trial, McLinden testified that the couple rekindled the relationship in October, 1986, and moved in together the following month. In January, 1987, Munyer announced she was pregnant, and the child was born six months later.

McLinden said Munyer told him the child was his and he believed her. He was listed as the father on the birth certificate and other records.

“I was led to believe this child was mine,” he said in an interview. “I attended Lamaze classes with Karen. . . . I went through the 12 hours of labor with her and was there when my son was born. It was one of the greatest moments of life.”

Munyer has testified that McLinden knew all along the boy was not his but agreed to act as his father and promised to marry her. When he reneged on the promise, she moved out in 1989. Later that year, she married David Munyer.

“Larry has known since the start he was not the boy’s father,” she said. “We did not restart our relationship until after I was pregnant.”

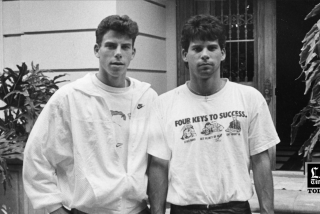

At the center of the controversy is the boy. Several times a month, the dark-haired child with an easy smile makes the trip up and down the San Diego Freeway between his mother’s home near Inglewood and McLinden’s in Canoga Park. McLinden and Munyer are now sharing custody equally under a court order.

The boy’s biological father is not conclusively known. A man Munyer claimed in court is the real father was ordered to undergo a blood test, but the analysis is not yet complete.

If the test determines he is the father, he could seek paternal rights, and Henry said she would then have to decide whether the rights she granted McLinden would supersede the biological father’s. The man, however, has made no claim of paternal rights so far.

McLinden, 43, who is unmarried, said Larry Jr. calls him “Daddy” and enjoys their time together.

“I have been there since his birth, and he looks to me as his father,” McLinden said. “He doesn’t know the difference between a father being biological or adoptive or other. He just knows me as his father. There is a tremendous bond between us.”

According to records in the case, a court-appointed psychiatrist who interviewed the boy agreed that he regards McLinden as his father and that maintaining the relationship is in the child’s best interest.

The psychiatrist’s report is expected to weigh heavily in the custody decision, according to Munyer’s attorney, Steven Rein. He and his client see the paternity ruling as the first step toward her losing custody of the boy.

“My son will be damaged by this,” said Munyer, who has two teen-age children from an earlier marriage. “He will be without his mother when he needs her.”

Munyer, 34, said the ruling also effectively blocks efforts by her husband of two years, David Munyer, to adopt Larry Jr.

“I don’t think the courts are really looking at what this will do to my son,” she said. “He calls Larry ‘Daddy’ because he buys him presents and takes him to Disneyland. He doesn’t understand. What happens when he grows up?”

In her ruling, Henry said that regardless of whether McLinden knew he was not the father, his actions in rearing the boy as well as Munyer’s representations that he was the father made him the “psychological” parent in both the boy’s and McLinden’s minds.

“Larry is clearly recognized by Larry Jr. as his father and the two have a strong, bonded relationship characterized by mutual affection and shared interest,” Henry wrote. “To terminate this relationship at this point would be a profound loss, which would likely result in adverse psychological consequences for this child.”

Henry’s ruling is not unique, though it may set a precedent in California, legal experts said.

McLinden’s attorney, Glen H. Schwartz, said Henry granted McLinden parental rights under the legal principle of “estoppel,” which holds that if a person holds a lie to be the truth, he or she cannot later use the truth as a legal defense.

In this case, Henry ruled, Munyer cannot stop McLinden’s paternity by now claiming he is not the boy’s father.

“Karen cannot create the false illusions and then unilaterally sever the bond,” Henry wrote. “She cannot unilaterally determine at any given time who the child’s father should be.”

Scott Altman, a USC associate professor of law and an expert on family law, said the principle of estoppel has been used most often to enforce paternity responsibility in a divorce when a man has sought to avoid paying support for children he did not father. In those cases, the man was held responsible because he led the children to believe he was their father.

But the McLinden case offers a rare opposite use, Altman said. He said similar rulings have set legal precedents in Michigan and Wisconsin.

In California, a similar ruling was made in Los Angeles Superior Court in 1987, according to the attorneys involved. In that case, which remains sealed from public view, a man was declared the father and awarded custody of a child he helped raise even though he did not father the youth or marry the mother.

But the case did not set a precedent that other courts can follow because it was never appealed, attorneys said.

Munyer has vowed to appeal Henry’s ruling, meaning an eventual published decision by the appellate court would set a precedent for California courts.

“It is clearly making new law,” Altman said.

Another unusual aspect of the case is the notice it has drawn.

Paternity cases are most often kept under seal. But in this case, the attorneys and their clients have agreed to discuss the case with the media, although the court still regards the matter as confidential. The parties involved have appeared on radio talk shows and given numerous other interviews. Television movie producers have even begun to make inquiries.

“I think it’s a story that should be told,” McLinden said. “I think there are other situations out there like mine where people don’t feel they have any hope. Hopefully, this will benefit someone else.”

Munyer said she has talked to the media because she believes the court system is not properly serving her son. She said she and McLinden have shielded him from the media and he is too young to understand the legal process.

Henry scheduled a hearing for Jan. 27 to address the custody issue. It is likely that one of the parents will win “primary physical custody” of the boy while the other will be limited to a visitation schedule.

Without being granted parental rights, McLinden stood little chance of gaining custody. Law experts said the courts historically have given custody to non-parents only when parents have been determined to be detrimental to the best interests of the children.

In this case, Munyer has not been found to be detrimental, according to Henry’s ruling. Therefore, Henry’s granting of parental rights to McLinden will give him equal consideration when the judge determines custody.

Regardless of the ruling, Munyer said she hopes her son will be allowed to stay with her.

“He needs his mother,” she said.

But McLinden said he intends to seek primary custody because he believes he can provide the most stable home for the boy.

“I feel I have put his best interests in the forefront since he was born,” McLinden said. “I have pursued this because of the love of my son. I knew if I didn’t pursue it I would lose him. It would have been devastating for both of us.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.