For 2 1/2 years, a group of women say they were terrorized by their apartment manager. Their repeated attempts to get help failed, until they banded together and fought back. : Harassed at Home

- Share via

FAIRFIELD, Calif. — Jim Skinner’s reign of terror began in January, 1987--as soon as he was hired to manage the Fairfield North Apartments in this small city halfway between Oakland and Sacramento. For the next 2 1/2 years, he inflicted on at least 21 single, low-income female tenants an increasingly severe pattern of sexual harassment and intimidation that is virtually unknown in American legal annals.

Jangling his keys like a jailer as he stalked the hallways of the modest, 112-unit complex, Skinner unnerved the women who heard him. They wondered: Is he coming for me this time?

For the record:

12:00 a.m. Dec. 5, 1991 For the Record

Los Angeles Times Thursday December 5, 1991 Home Edition View Part E Page 13 Column 1 View Desk 2 inches; 57 words Type of Material: Correction

Sexual harassment--A Nov. 24 story in View about a sexual-harassment case at a Fairfield, Calif., apartment complex contained erroneous information provided by a Solano County deputy district attorney. Lyn Skinner, wife of the complex’s former manager, was not convicted of misdemeanor welfare fraud in 1989. Officials dismissed charges against her for health reasons. Her husband pleaded guilty.

They had good reason to fear.

According to depositions taken for a lawsuit the women eventually filed, Skinner would let himself into their apartments while they slept or showered, surprising them when they awoke or entered a room. He grabbed their breasts or genital areas in public, sometimes in front of others. He cajoled them into posing in lingerie to make up for unpaid rent and asked them to watch pornographic movies with him. He insisted their boyfriends sign in for overnight visits, imposed curfews and had their vehicles towed. He riffled their mail and withheld welfare checks, threatening to accuse some of fraud when they received small monetary gifts from relatives. He dangled the prospect of subsidized apartments in front of many of the tenants and never came through.

Even worse, say the women, he used their children as pawns.

Skinner forced some women to ground their children and told selected youngsters to stay off common play areas or their mothers would be evicted. (“You know what that means?” he told one tenant’s 7-year-old son. “That means you and your Mommy will be sleeping in the park.”) He displayed his guns to children. Several women said they received a visit from Child Protective Services after he made bogus abuse reports. (“It was like the Angel of Death had knocked on my door,” said one woman who received a note from the agency.)

Skinner was able to do all this because he constantly threatened eviction, and sometimes followed through when women would not accede to his propositions. And even after he evicted them, Skinner would park in front of their new homes and call them at work to make threats.

The litany of harassment is remarkable. But the more compelling story is how a group of isolated, traditionally powerless women found each other, faced down an awesomely intransigent bureaucracy and turned the tables on their tormentor.

For two years, almost every official and advocacy group to whom the women turned either conducted a cursory investigation and exonerated Skinner, refused to help or simply could not help. The women contacted their landlord, the police, their congressman, the National Organization for Women, the U.S. Postal Service, the Department of Consumer Affairs, the ACLU, Child Protective Services, social workers and perhaps a dozen attorneys who specialized in sexual harassment.

“He was confronted over and over and not punished,” said Molly McElrath, who was forced by Skinner to sign false complaints against her neighbors or face eviction. “He was empowered by it. He became a monster, inevitably.”

Ultimately, the government did step in: Their complaints prompted investigations by the federal department of Housing and Urban Development as well as the state Department of Fair Employment and Housing. But in the interim, because they wanted to move faster, two of the women found a pair of feminist attorneys who sensed right away the case was a winner. The lawyers asked the two women to gather potential witnesses. What they got were more plaintiffs. They quickly filed a lawsuit on behalf of 13 women.

Earlier this year, well before Anita Hill inspired an unprecedented public discussion of sexual harassment, the women made history. They won what is believed to be the largest settlement in the relatively new area of sexual harassment in housing. (See accompanying story.) Invoking 31 statutes, from the Fair Housing Act to anti-trespassing laws, they and their 25 children were awarded nearly $600,000 in individual awards that ranged from $12,000 to $60,000 for the adults and up to $6,000 for the children. Their attorneys were awarded another $259,000 in fees. Neither Skinner nor the apartment owners admitted guilt and neither will comment. The settlements were made to five plaintiffs in January and eight in June. The money was paid by the complex’s insurance companies.

“I personally know of no other case with this number of women over this period of time with this variety of assaults,” said attorney Leslie Levy, who, with partner Amy Oppenheimer took the women as clients.

“I’ve done this kind of work for 11 years,” said HUD investigator Paul Smith. “And I haven’t heard stories like this ever.”

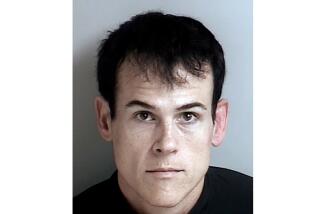

Some of the former tenants are now sitting behind the wheels of new cars. Some are sitting in new homes. And Jim Skinner, 40, is sitting in Solano County Jail, awaiting trial on charges he raped two women--one a tenant; the other, her sister.

Not one of the tenants was in it for the money. Way back when all the trouble started, all they wanted was for James H. Skinner to go away.

A roly-poly man with thick brown hair, a soft Southern twang and two ex-wives, Skinner says in his resume that he grew up and attended school in Alabama. The resume says he was in the Air Force between 1970 and ‘75, and attended college for a couple of years. He has three children with his third wife, Lyn, 31, who believes her husband is innocent of all charges.

“People thrive on all this crap,” said Lyn Skinner, who lives near Gilroy and gets by on welfare. “He is a wonderful husband and a fantastic father.”

Married seven years, the Skinners met when they both worked at Kmart in South San Francisco.

Ironically, while he was threatening to turn in tenants for welfare fraud, he and his wife were under investigation for the same crime. In 1989, the Skinners were convicted and received probation, said Solano County Deputy Dist. Atty. Kathryn Coffer.

Tenants recalled that Skinner had seemed extraordinarily friendly when he arrived at Fairfield North nearly five years ago. He knocked on doors, introducing himself ebulliently. But the friendliness soon became menacing.

To cope, many of the women say they simply shut themselves in. They drew the curtains and kept their children inside. Once Skinner became aware that the women were trying to take action against him, he warned them not to associate with each other, or face eviction. They developed an “underground,” whispering over the hum of washers and dryers in the laundry room.

Elizabeth Howard, whose 3-year-old son was given to ear-splitting temper tantrums, remembers sobbing in fear as she held the boy on her lap in a closet, her hand clasped over his mouth so Skinner would not hear the boy and call protective services.

“In the beginning, no one put it together and said, ‘OK, we are being sexually harassed,’ ” said Catherine Hanson.

“All we wanted was for him to be fired,” Hanson, a mother of two, was forced to disband the award-winning single parents group she founded with McElrath after Skinner implied loudly and publicly she was operating a prostitution ring.

One day, in May, 1987, when members of the support group were picnicking on the lawn, Skinner yelled that Hanson was operating an illegal business on the premises and that she had better stop “soliciting” and get her “girls” off his property. Hanson was horrified when men in the complex approached her to have sex for money.

Hanson, a resource specialist, found herself besieged by women asking for help and decided it was time to fight back.

She wrote a letter to the complex owners accusing Skinner of intimidation tactics, invasion of privacy, attempts to overcharge for repairs, sexual harassment and unduly restrictive rules. It was signed by 11 tenants and mailed in June, 1987. Two months later, Mark Chim (who with his wife, Marilyn, is the primary owner of the complex) responded:

“We are all aware of that certain sense of loyalty to former resident managers which makes it rather difficult for a new manager to gain acceptance among some tenants. We have discussed this concern with Mr. Skinner and he has agreed to demonstrate more consideration when he communicates with some of the existing tenants who may be resistant to his management style.”

Besides, wrote Chim, Skinner had done a wonderful job landscaping the property.

By the second half of 1988, the harassment was escalating.

Elena Fiedler lived in a shelter for battered women with her three children before moving to Fairfield North in July, 1988. When she brought her first rent check to the office, she said, Skinner ran his hands up her leg, grabbed her crotch and said, “I’ll take everything you’ve got.” Her 8-year-old daughter witnessed the exchange.

Debra Boucher-Kallhoff awoke one night in September, 1988, to find Skinner next to her bed, his shirt off and his pants around his knees. Disoriented and terrified, she pushed him out the door and tried to push him down the stairs.

“I’ll get you for this,” he snarled. She strung empty tin cans across her doors after that. She was evicted later that month.

In December, 1988, Yvonne Lindsey, the mother of two boys, lost her job. Skinner told her she could earn rent money by donning lingerie and posing for photographs that he would sell to Sears or JC Penney. First, though, he wanted to check her for stretch marks. She refused and was eventually evicted.

Jane Clark, an executive at the Vacaville Reporter, was not about to let her daughter, Boucher-Kallhoff, be evicted without taking action. She had no idea that Skinner had entered Debbie’s apartment or that he had grabbed her breasts several times and asked to watch pornographic videos with her.

Clark, a corporate trainer who had just given a seminar on sex harassment to a group of newspaper managers, only knew that Skinner was out of line. There was no reason to evict her daughter, whose rent was paid in full. Also, Skinner had posted her daughter’s eviction notice on her front door--Clark lived in the condos across the street--because she was a co-signer on her daughter’s lease.

For the next several months, Clark would spend long nights writing letters, making phone calls, urging the state Department of Fair Housing and Employment to look into the case. She discovered after contacting Legal Assistance that there were other tenants who had been harassed. When the DFEH closed the case for lack of evidence, she drove to Sacramento, spoke to the department’s chief and got it reopened.

(DFEH found cause to proceed with a lawsuit, but suspended action when the tenants pursued it privately.)

In early spring of 1989, HUD’s Paul Smith got involved, continuing an investigation begun by his predecessor.

Smith contacted McElrath, Hanson and Sandford, all of whom had moved out of the complex, and enlisted their help in finding women who would give statements. Even then, all the women wanted was for Skinner to be fired.

That would not happen until June, 1989, at a tense meeting that owner Chim called only when the women threatened to picket the complex and alert the press.

Before the meeting, Skinner threatened women who were still living at Fairfield North that they would face eviction if they attended. Then he asked Elena Fiedler to attend as his spy.

Secretly, she was thrilled. It would be her dramatic statement about how he had grabbed her crotch that would finally do it: When Chim heard that, said the women, he looked sick. Skinner was let go--with three months’ pay and a letter of recommendation.

Clark, however, was not satisfied. Skinner might be gone, but no one had made amends to her daughter. In October, 1989, after interviewing many attorneys, Clark and Boucher-Kallhoff finally found Levy and Oppenheimer, who work out of a cramped suite of offices in north Oakland. They specialize in sexual harassment and discrimination cases.

Levy took the case without hesitation.

“Jane and Debbie came down and met with me one evening. I thought I was doing an hour (preliminary interview) and several hours later, I called Amy and said, ‘Guess what just walked in the door?’ ”

Oppenheimer was dubious. Did they have the resources to devote to such a case? On a contingency basis? But Levy was adamant.

“Sometimes you get that feeling by listening to their stories, by listening to their tone and level of fear and concern,” said Levy. “And they had something you almost never get: an incredible amount of documentation.”

The civil suit was filed in federal court in October, 1989. Then depositions were taken. Skinner was in England. He was sent a plane ticket by attorneys for the apartment complex, but he never showed up for his deposition. He was later discovered living in Florida. As a result, a default judgment was entered. Last July, without admitting guilt, the apartment owners and their insurance companies settled.

The Chims’ lawyer, Deborah Bjonerud, said neither she nor the Chims will talk about the case, since a similar lawsuit brought by eight other former tenants is pending. The Justice Department is representing those women.

When it was settled, the first case made headlines in Northern California. The women appeared on local television talk shows. The NBC show “Expose” profiled them.

Skinner was still at large.

Almost immediately, Levy and Oppenheimer received a tip that he was working at an apartment complex in Cupertino. This was chilling news.

“To suddenly find out he is not across an ocean, not in Florida, but across the Bay Bridge, the reality hit us in the face again, and all the bravery disappeared,” said Hanson. “It was like, ‘Oh my God, he is gonna come after us!’ ”

But something else was about to happen that would result in his incarceration and ease their worries. After learning that Skinner was living nearby, a woman who had lived at the Fairfield apartment complex contacted a rape crisis line. A counselor brought her to Fairfield police. In 1988, she said, she had been raped by Skinner. What’s more, her sister came forward with the same charges: she, too, had been raped by Skinner, she said.

Fairfield Police Detective Harold Sagan obtained a warrant for Skinner’s arrest in July. He tipped off the women who had just won the judgment because they wanted to witness Skinner’s return--in handcuffs--to Fairfield. They gathered--queasy and jittery--behind the Solano County Jail and in a spontaneous gesture they grabbed their keys and jangled them at Skinner when the police car pulled up.

“I think the evidence will probably show that Mr. Skinner was in many ways insensitive to these women and perhaps very chauvinistic in a lot of his actions,” said Solano County Public Defender Peter Foor, who is representing Skinner. “(But) he is not guilty.” Skinner does not deny that sex with the two women took place, said Foor, but he claims it was consensual and for money.

It is hard to imagine that this short, doughy man in the royal blue Solano County Jail togs was the terror of Fairfield North. Separated from his visitor by a thick pane of glass, with a telephone in his ear, he is stripped of the ability to menace.

“Sorry ma’am,” he says nervously, “I am not allowed to talk to anyone.”

With bail set at $100,000 it is unlikely Skinner will be out of jail anytime before his trial on two counts of forcible rape, two counts of forcible oral copulation and one count of rape by a foreign object. He is alleged to have brandished a gun in one case.

If convicted on all counts, said prosecutor Coffer, he may receive up to 46 years in prison, half of which he can be reasonably expected to serve. The trial is slated to start Jan. 13.

Some of the 13 tenants whose case has been settled have formed a group, Women Refusing to Accept Tenant Harassment (WRATH). WRATH will promote public awareness of sexual harassment in housing and will provide resources and information to women in need. When the group receives nonprofit status, it will be launched with a $10,000 grant from the offices of Levy & Oppenheimer. Unlike other advocacy groups, said Hanson, WRATH will be a place where a woman really can get help.

Most of the women say their ordeal was not without an upside. They have become stronger, more self-confident and less tolerant of any kind of harassment.

One evening two weeks ago, Annette Sandford, who fought Skinner’s attempts to evict her for months until she got married and moved out, summed up their sentiments pretty well. Sitting at the kitchen table of her Suisun City house, her elbow resting on a stack of legal documents and letters she compiled while fighting her eviction, she puffed on a cigarette and smiled.

“The best thing is I am vindicated,” she said. “Skinner is sitting in jail and that is where I wanted him to be. Now he has someone controlling his comings and goings. I am so glad he is in there. And there is always the possibility that he is being sexually harassed.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.