Drug Reimbursement Limits Criticized : Health care: Researchers find that admissions to nursing homes doubled when New Hampshire began a policy of restricting payments for medicines.

- Share via

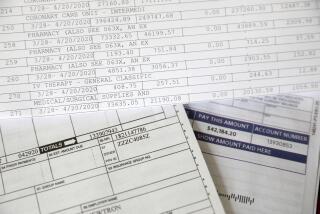

A common strategy for holding down health care costs--putting a monthly cap on insurance reimbursement for prescription drugs--can end up inadvertently hiking costs by driving vulnerable patients into nursing homes, a new study has found.

The study, published today in the New England Journal of Medicine, examined what happened when New Hampshire limited Medicaid patients to three reimbursed prescriptions per month--a practice it has since abandoned. Drug use during that period dropped by 35% but the nursing home admission rate doubled.

“In short, the policy was penny wise and pound foolish,” two health policy experts wrote in an editorial published with the study, one of the first to demonstrate that restrictions on reimbursable medical services for the poor may end up costing more than they save.

The study comes at a time of mounting pressure for health cost containment and concern about some policies’ effects--specifically, concern that they might worsen the quality of care and harm the health of the poor, chronically ill and elderly.

About one-quarter of state Medicaid programs have limits on drug reimbursement, the researchers said. Ten states limit reimbursement to six prescriptions a month or less. Three of those--Texas, Oklahoma and South Carolina--set the limit at three prescriptions. The authors said California does not limit reimbursable prescriptions.

“Our findings raise questions about the clinical and economic wisdom of such policies,” the authors wrote. They concluded that the New Hampshire policy probably ended up costing the state more in nursing home billings than it saved on prescriptions.

The researchers examined claims filed with the state Medicaid program by 411 patients over the age of 60 who were being treated for chronic illnesses before, during and after the state began its short-lived policy capping monthly drug reimbursements in the early 1980s.

They compared those records to claims filed in New Jersey, the only Northeastern state with no Medicaid cost-sharing schemes or payment limitations for drugs at that time. Before the New Hampshire policy, both states had similar nursing home admission and drug use patterns.

The number of reimbursed prescriptions per month per patient dropped 35% after the cap was imposed, the researchers found. It returned almost to normal after the state, under public pressure, replaced the cap with a $1 patient co-payment on all Medicaid prescriptions.

Similarly, the nursing home admission rate rose to nearly twice that of New Jersey, then returned to normal when the policy was abolished.

The drugs involved included treatments for serious, chronic conditions including diabetes, heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, seizures and conditions requiring treatment with blood-thinning drugs.

It is unclear how much of the leap in nursing home admissions is traceable to patients becoming sicker for lack of drugs and how much is traceable to patients entering nursing homes to skirt the reimbursement limit, which did not apply to institutionalized patients.

“Regardless of which mechanism explained the excess admissions, the economic impact of preventable institutionalization and its effects on quality of life are severe,” wrote the authors, headed by Dr. Stephen B. Soumerai, an associate professor of social medicine.

In an interview, Dr. Steven A. Schroeder, president of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and an author of the accompanying editorial, said there have been other indications that certain cost-containment measures have ended up increasing costs.

For example, hospital payment systems aimed at eliminating unnecessary stays have successfully shifted many procedures to outpatient clinics--but also spawned a new outpatient surgery industry while failing to shrink hospital overhead, Schroeder said.

“The generic problem is that states are wrestling with spiraling Medicaid costs, a budget crisis (and) taxpayer reluctance to pay more taxes,” Schroeder said. “So they’re looking for answers. What’s missing is national leadership to take a comprehensive look at the problem.”

In their editorial, Schroeder and Dr. Joel C. Cantor argue for a multipronged approach to cost containment that would address patient demand for services, pricing, malpractice, inappropriate use of procedures and physician supply.

“Perhaps the most important lesson from the New Hampshire experiment is that although the poor are a tempting political target for cost-containment efforts, those who seek a quick and politically painless solution may be deceiving themselves, as well as harming others,” they wrote.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.