BOOK REVIEW : The Day of the Dolphin Is Getting Closer : DOLPHIN SOCIETIES: Discoveries and Puzzles <i> Edited by Karen Pryor and Kenneth S. Norris</i> , University of California, $34.95, 400 pages

- Share via

The first Queen Elizabeth loved dolphins so much she decreed them the Queen’s Fishe, royal property. What she loved was their oily taste.

No matter. Out of this peculiar regal predilection grew the remarkable collection of cetacean skeletons and teeth at the British Museum. These teeth, writes Karen Pryor in this major anthology of dolphin research, mark a dolphin’s age much as rings chronicle a tree’s lifetime.

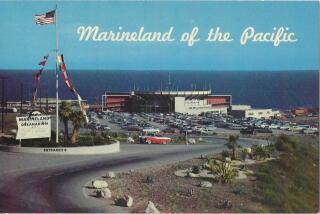

Between them, Pryor and co-editor Kenneth Norris have 63 years of experience working with dolphins. Norris, a professor at UC Santa Cruz, became involved with dolphins in Florida in the late 1930s, when a group of movie makers created Marine Studios (later Marineland, Florida). Twenty years later he met Pryor in Sea Life Park in Hawaii, an institute she founded to pioneer dolphin training. Pryor describes how the 1960s television show “Flipper” transformed dolphins from intriguing animals into “a sort of floating hobbit.” Once dolphins were on screen, their protection was a shoo-in.

Unlike most mammals, dolphins instinctively make intense and readable eye contact with people. This innate behavior helped rally support for the Marine Mammals Preservation Act of 1972, what Pryor reminds us was “an utterly unprecedented piece of environmental legislation.”

It established the Marine Mammal Commission, on which both editors of “Dolphin Societies” have served. It is the only governmental agency that must take the advice of its scientific advisory board or explain to Congress why not.

With the act protecting them and the availability of new technology--like aerial surveillance and radio tracking--marine biologists got to work. They asked questions about dolphins in the language of ethology (the study of animal behavior), the same language being used to describe the lives of chimpanzees, gorillas, lions and hyenas in the wild.

The answers they found are in the 13 scientific papers by American, Japanese, Australian and Soviet naturalists contained in “Dolphin Societies.” They describe dolphin behavior in the wild and in captivity, and they explain what has been learned from the remains of dolphins in the laboratory.

Distinguishing this volume from most scientific collections are five remarkable editorial essays laced between the diagramed, data-filled presentations. Gifted writers, Pryor and Norris combine the new data with accounts of their own experiences, interpreting dolphins in the context of what is known about such other intelligent, non-human mammals as chimpanzees.

Tracking animals underwater is difficult, but not much harder than tracking birds. In fact, dolphin watchers have adapted a tool of ornithologists: radio implants, designed to work underwater, to “tag” sample animals. They have borrowed the methods of primate language study to devise systems of measuring how dolphins manipulate symbols.

A chapter on “Dolphin Psychophysics” describes blindfolded dolphins finding objects by echolocation, a biological sonar system so highly developed that “to say that dolphins echolocate is like saying Michelangelo painted church ceilings.” Most dolphins live in matriarchal groups. Some individuals live more than 60 years, maintaining steady bonds with other animals including, very often, their mothers.

Among the more remarkable discoveries reported in “Dolphin Societies” is the role of females no longer giving birth. Female dolphins, like female humans, stop ovulating about halfway through their lives.

Yet they remain active for 30 more years. And although they cannot become pregnant, they continue to have sexual intercourse with males, to produce milk and nurse their adult offspring. Milk has been found in the stomachs of dolphins as old as 20.

Sexual play seems to be the social glue of dolphin society. Like pygmy chimpanzees in the forests of Zaire, this highly social and generally peaceable species uses sex to affirm familiarity and, perhaps, connectedness.

Sex also seems to maintain social hierarchies. Observers have noted dolphins resting in rank, the lowest at the bottom, farthest from the surface and fresh air. Understanding rank, Pryor explains, allows trainers to control whole groups.

Pryor describes a fascinating experiment from her experiences as trainer, a scheme for getting dolphins to perform new tricks. She fed and praised them--not for repeating what they had already learned but for devising something new. They caught on quickly, creating one new act after another.

Not hobbits, certainly, but not like any other animal, dolphins are highly trainable and seem predisposed to cooperating with man. Now that people are beginning to breed bottlenose dolphins successfully in captivity, dolphins may become the newest animals to accept domestication and could assist in exploration of the ocean.

Next: Jonathan Kirsch reviews “The Hitler Diaries” by Charles Hamilton (University Press of Kentucky).

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.