Legacy of WPA’s Massive Relief Program Endures 50 Years Later

DEEP GAP, N.C. — Russell Wellborn was sitting on his tractor tire in his shed the other day talking about hard times. He is 81, still working, and has seen his share of them.

“I’m down to a crew of three, just me and two other carpenters,” he said. “There’s no work to be had. We’ve found a few scattered jobs here and there but most times nothing at all.

“If it keeps on like this, it could get worse than the ‘30s. At least back then everybody had a little farm, or everybody around here did. We didn’t need much money. Now all the small farms are gone and you have to have cash to get by.

“And of course,” he said, as if no more needed saying, “back then we had the WPA.”

America’s Great Depression of the 1930s could well have been named for this one remote corner of the land deep in the Blue Ridge Mountains, where Russell Wellborn was delivered by a midwife and educated in a log school. Here, unemployment was almost total. And, yes, evidence abounds a half-century later that the beleaguered souls who survived it did indeed have the WPA. Its legacy is everywhere.

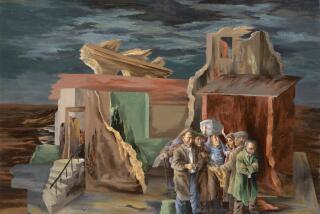

In Boone, the next town west of here, the old native-stone post office, with its granite counter and brass inkwells, is evidence of the WPA. So is the heroic mural above, honoring the town’s eponymous Daniel Boone, signed in 1940 by a forgotten artist named Alan Tompkins. So is the Boone school evidence of the WPA and 49 other school buildings in Watauga County. So is the county library and so is the 635-page “Guide to North Carolina” on its history shelf. All evidence that for six years the WPA flourished and left its mark.

The WPA--Works Progress Administration--was the basic social and economic program of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. It began in the summer of 1935 and had wound down by the summer of 1941 when the threat of war and a booming armaments program created new jobs. It was officially abolished by presidential order in December, 1942.

In those six years, more than 8 million unemployed men and women across the nation, 20% of the labor force, built 20,000 schools, hospitals, libraries and gymnasiums. They built water lines, sewer lines and mile after mile of farm-to-market roads where none existed. It was in many respects a clumsy, bureaucratic monster--it took the president four press conferences to explain it--but “the essential fact remains,” according to historian Nathan Miller,” that it was the largest and most successful relief operation in American history.”

Certainly its most durable. If, for example, out in the American countryside you should come across a mossy old stone bridge still doing its job, you likely will find on it a date in the late ‘30s. The reports of the nation’s infrastructure falling apart do not, ironically, include many of its oldest structures. Those WPA bridges were built to last.

“The highway people want to widen 221 out east of here,” Russell Wellborn mentioned. “But they would have to rebuild the bridge where 221 goes under the parkway, and they can’t find masons who do that kind of stone work anymore. So they’re hung up.”

The parkway he is talking about is the Blue Ridge Parkway, a 470-mile stretch of extraordinary scenery along the sinuous spine of the loftiest ranges east of the Rockies. It connects the Shenandoah National Park in Virginia with the Great Smokies National Park in Tennessee, passing through North Carolina. Breathtaking. It was one of Roosevelt’s pet WPA projects.

The bridge that crosses over U.S. Route 221 at Deep Gap is one of 105 bridges, culverts and retaining walls built along the parkway between 1935 and 1941, all good as new, showing for all their age only a reassuring patina of long service.

They were built of native stone taken, geologists say, from some of the oldest mountains on the planet. Taken, sculpted and returned. The 22 million people who visit the parkway annually can still see on the rock faces the marks of the hand drills of the blasting crews. Hand drills, not power drills, because the idea of the WPA was to put to work as many people as possible as close to home as possible with as little cost as possible in machinery and materials.

And to start them working as quickly as possible. Hundreds of men began building the parkway simultaneously in segments all along the route and joined them later. It was the practice throughout the land.

“I guess there are more efficient ways to build a road,” said Harley Jolley, “but the main purpose of WPA was relief, not efficiency.” Jolley is a retired history professor at Mars Hill College just up the parkway from Asheville, N.C. (The high school at Mars Hill, still in use, was WPA built.) He has made a lifelong study of the parkway and its builders.

“Most of these mountain people would rather starve than go on the dole,” Jolley said. “So to them the WPA was a godsend. It saved their lives and also their self-respect.”

The WPA was a model of inefficiency, all right. It added the Scottish word boondoggle, meaning an unearned reward, to the American idiom. Cartoonists of the period had a field day showing men leaning on shovels. Indeed, even Roosevelt, during the 1936 election campaign, told one of his speech writers, Judge Samuel Rosenman, how much fun he would have if he were his opponent.

“I would cite chapter and verse on WPA inefficiency,” he said. “There’s plenty of it--bound to be in such a vast emergency program.” He considered that a moment, Rosenman told an F.D.R. biographer, and grinned. “You know,” he said, “the more I think about it the more I think I could lick myself.” Criticized it may have been, but when Roosevelt passed through Marietta, Ohio, an old woman knelt where he had stood, bent down and kissed his footprint in the dust.

Russell Wellborn found work on the Blue Ridge Parkway, cutting brush. His brother Ed worked on a drilling crew. The parkway fed the families, and the dignity, not only of out-of-work manual laborers and skilled craftsmen but also engineers and landscape architects and accountants and countless clerks and paper shufflers in three states. “They all held on to their talents and skills until good times returned,” Jolley said.

Honoring the past, the WPA restored Ft. Raleigh on Roanoke Island, N.C., and the historic Dock Street Theatre in Charleston, S.C. Looking ahead, the WPA built airfields, mainly in medium-sized cities such as Asheville, Charlotte and Pinehurst in North Carolina, but also in New York City where 5,000 men working three shifts six days a week built La Guardia Airport in two years. A year later it became the world’s busiest airport.

And, as if to promise that good times would indeed return some glory day, they built 313 public golf courses and remodeled another 389. Bobby Jones, the most celebrated golfer of the era, served as unpaid consultant.

For many Depression schoolchildren, a WPA lunch was their only hot meal of the day. This generation’s Head Start program, the most successful enterprise of Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society, had its origin in WPA nursery schools. WPA workers staffed dental and medical clinics, rural and urban. They translated millions of pages into Braille and taught thousands of illiterates to read, the seedbed of adult education programs in many cities today. When Key West, Fla., went bankrupt, the WPA took over municipal functions to keep the city operating.

From coast to coast, WPA sewing rooms sprang up in attics and basements of public buildings. In one nine-month period, 700 women in Buncombe County, North Carolina, recycled Army uniforms into 68,000 overalls, dresses and baby garments for distribution to the indigent.

Across the continent, at Mt. Hood, Ore., recycled sewing room scraps were recycled again into bedspreads, curtains and hooked rugs; abandoned railroad tracks were recycled into andirons and chandeliers and recycled railroad ties sculpted into newel posts. The result was the grand and soaring Timberline Lodge. The purpose was not so much to build a national landmark but to provide 500 jobs for artisans.

Looking back, it is hard to find an area of American life not touched by the WPA. But perhaps its most notable innovation was the inclusion in a federal relief program of unemployed actors, musicians, artists and writers.

“Why not?” Roosevelt said. “They are human beings. They have to live.”

The arts enterprises cost only a fraction of the $10 billion laid out for the WPA over its six-year span. But the four projects, lumped together under the shorthand reference Federal One, may have attracted the most attention.

This generation’s National Endowment for the Arts is a descendant of Federal One, complete with controversy. But for all the squabbling, the records show that in 1936, more people in the United States attended WPA shows and listened to WPA music than all other performances and concerts combined, mostly in places that had never known live theater or symphonic music.

More than 150 resident acting companies put on everything from Shakespeare in school auditoriums to puppet shows in orphanages and children’s wards. WPA dance bands and orchestras showed up for free concerts in city parks and hoedowns in Grange halls and mining camps.

Box-office counts showed that 30 million people attended Theater Project productions. The project introduced to America many whose names would later appear in lights: Orson Welles, Arthur Miller, John Huston, Joseph Cotten, E.G. Marshall, Arlene Francis, John Houseman, George Izenour to name just a smattering. Burt Lancaster began his career as an aerialist in a WPA circus.

The Music Project as well exposed America’s untapped talent. Besides bringing cheer to a nation desperately in need of it, it produced 5,300 original works composed by 1,500 WPA musicians, an undreamed of creative opulence. Musicians who got their start in the WPA wound up in a dozen of the nation’s symphony orchestras, two as conductors. Indeed, the North Carolina Symphony Orchestra began as a WPA group.

Federal One’s even more conspicuously successful effort was the Federal Arts Project. It was, says historian William McDonald, “in material, size and cultural character unprecedented in this or any other nation.”

The centerpiece was its murals program. Private patronage had dried up for America’s artists, but walls were free and paint was cheap. Murals blossomed in hospitals, schools and public buildings, from the airport in Cincinnati to the post office in Boone, N.C. In all, more than 6,000 artists, eager to earn the standard rate of $23.86 a week, went to work in all 48 states.

Well, 46. The WPA director in Vermont believed that needy artists ought to do manual labor, “something worthwhile.” The Texas director was afraid the artists might try to sneak some subversive message on a Texas wall. Both refused to participate.

The murals, though, tended more toward heroic themes and local history, such as the mural in the Boone post office. Unlike the surviving Boone mural, others, neglected over the past half century, are long gone.

Even those, however, seem to have taken on the fascination of sunken treasure, especially if the artists who painted them became famous.

It was known, for example, that Arshile Gorky, a premier American painter of the day, had painted 10 panels for the Newark Airport. Two of them have been recovered under 14 layers of paint.

A recent survey by New York’s Municipal Art Society found that only about 200 WPA murals remain of more than 500 commissioned, and some of those too far gone to restore. But others were deemed well worth saving and the society is raising money to do that. One, by Ilya Bolotowsky, had been painted over five to seven times in a hospital on Roosevelt Island. Another, by Charles Alston, one of the black artists who got his start in the WPA, is peeling off the wall in Harlem Hospital. Both will be saved.

The Art Project produced its own long list of illustrious names: Jackson Pollock, Ben Shahn, Willem de Kooning, Anton Refregier, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Aaron Bohrod and Stuart Davis.

So did the Federal Writers Project. Future Nobelist Saul Bellow worked for the WPA. So did Ralph Ellison, John Cheever, Conrad Aiken, Studs Terkel, Nelson Algren and Arna Bontemps. Richard Wright wrote by day for the WPA, which sustained him while he wrote “Native Son” by night.

The Writers Project is most remembered for the detailed guidebooks for every U.S. state and territory. But its 6,000 writers also gathered first-person narratives of more than 10,000 Americans, people who likely never would have left a record, including the life stories of more than 1,000 former slaves.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.