Nate Archibald Is Still Doing His Best Work in a Gymnasium

- Share via

NEW YORK — It’s a weekday afternoon, and Nate “Tiny” Archibald is -- where else? -- inside a gym.

But there’s no thump of a bouncing basketball, just the squawk of a metal detector; no squeak of sneakers, only the blare of a too loud television; no crowd cheering wildly, simply the silence of row upon row of beds.

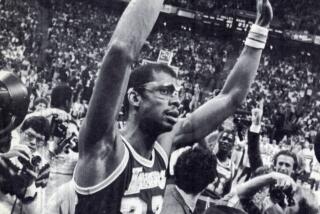

This is the Harlem Armory, a homeless shelter where Archibald -- NBA All-Star, starting guard on the 1981 champion Boston Celtics, Hall of Fame inductee on May 13 -- spends six nights a week helping out.

The shelter is home to 600 of the city’s dispossessed men, many of them addicts or alcoholics. Tiny Archibald grew up among them; basketball was his ticket out more than two decades ago.

Tiny is back now, spending more than 30 hours a week as recreation director for the shelter. He runs ping-pong tournaments, hustles tickets for outings, plays hoops with the homeless.

How did Nate Archibald, comfortably retired superstar, land here?

It was easy. Archibald, who came to the armory in January 1990, said he knows what these guys are going through.

“When I first got out of the NBA, I was in a transition. I was homeless. I didn’t have any direction, I didn’t know where I was gonna go,” said Archibald.

“And I know a lot of people don’t believe that: ‘Hey, this guy made a lot of money, he made a lot of connections.’ Not necessarily. I think that when guys get out of the NBA, they’re in a major transition. For 13 years, all I did was play basketball.”

That’s not the case these days. The shelter is not the only place Archibald still hands out assists; he spends his mornings at various Harlem schools as a drug counselor for Project Decision. And he’s working toward a Ph.D. in human resource administration and adult education at Fordham University.

Not bad for a guy who left college without a degree 21 years ago.

“I decided that in order to keep my mind and myself occupied, I had to get involved in a program where I’m always helping,” said Archibald, sitting in a rickety seat in the armory’s bleachers.

“People always helped me when I was younger. And in order to keep sanity, you have to keep occupied. If you have idle time, nothing to do, it seems like you’re thinking about some of the negatives and not the positive.”

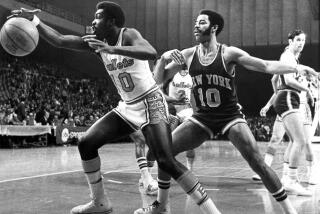

The on-court image of Archibald is unforgettable: pushing the ball up court, knifing between two bigger defenders, the left hand flicking the shot, a whistle and a foul as it drops.

“My thing was, I always liked the way guys handled the ball. People say, ‘Well, what about Michael?’ I love Michael Jordan. I could never jump like Michael Jordan,” Archibald recalled, smiling easily. “People ask, ‘Did you ever have any dunks in the NBA?’

“Never.”

Archibald did much more, though. In 1972-73, he became the first -- and only -- player to lead the NBA in scoring and assists in a single season: 34 points a game, more than 11 assists. He averaged nearly 19 points a game for his career, which ended in 1984.

Archibald, at 42, is still a lean 6-foot-1, still looks like he could take it to the basket. But the Harlem Armory is a long way from the parquet floor of the Boston Garden.

The building, on 143rd St. off the Harlem River, is a rough spot in a rough neighborhood. The wind whips off the water; the concrete structure appears just as cold.

On a recent afternoon, two men smoked crack behind a dumpster outside. Inside, the homeless are run through metal detectors before they are allowed to stay.

One man surrenders a tire iron from the trash bag that holds all his possessions. “Don’t lose that,” he tells a security guard. “I need it back when I leave.” Another man, stumbling drunk, holds up an empty bottle of booze.

“I got rid of it outside, just like you said,” he cackles at the guard.

Archibald is unfazed. The shelter residents greet him by name and joke with the ex-NBA star. Wearing a laminated ID reading “Nathaniel Archibald,” Tiny is as comfortable here as he was on the court.

“He is definitely a motivating force. He has an uncanny ability to communicate. The guys looked forward to seeing him,” said Bernard Johnson, the shelter director. “Coming in here, when he really didn’t have to, I was taken aback by the time he spends here.”

The homeless -- clients to the city bureaucracy, “the guys” to Tiny -- agree.

“He treats everybody as a human being. He doesn’t degrade you because you’re homeless,” said Big Bob, 30, an Adelphi College graduate who now lives on the streets.

Bob’s longtime running mate, 30-year-old David Scott, called Tiny “the most valuable player of the shelter system.” Both men knew Archibald from the basketball camps he ran each summer while home from the NBA; they now play for Tiny’s All-Stars, the team of homeless players coached by Archibald.

But Tiny brushes aside such praise.

“I don’t think it’s that much different than coaching,” Archibald explained. “The bottom line is I think I’ve been very successful in here, and I’ve won here. A lot of coaches don’t feel that way.”

Archibald wasn’t sure where he stood when an injury knocked him out for the 1977-78 NBA season. Unsure of the future, he returned to college and received his undergraduate degree.

After retiring in 1984, Archibald went on to become an assistant basketball coach at Georgia and the University of Texas at El Paso. Frustrated by his inability to advance, Archibald returned to school and the neighborhood where he was born.

Tiny’s acutely aware most ex-NBA stars don’t do the work he does. Celtics teammate Cedric Maxwell once said he liked to spend his leisure time sitting near construction sites, watching people work.

But Archibald said it’s important for children to have role models, and professional athletes must realize that’s what they are.

“They are role models, whether they accept it or not. You are on a different pedestal than a person who works 9-to-5,” said Archibald. “When Michael (Jordan) does the commercial about staying in school, people look up to that. ... There’s got to be more positive role models.”

Tiny is a role model, albeit one with a lower profile than in the days when he tore up the NBA. The students Archibald works with never saw him play. The guys in the shelter did, but they’re more concerned with what he’s doing now.

Archibald likes it that way.

“When you take the uniform off, you look the same as everyone else. You don’t have a number, and you don’t have your name on the back,” said Archibald. “And it’s not about what you did. It’s what have you done lately?”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.