McGregor Not Interested in Baseball Comeback

- Share via

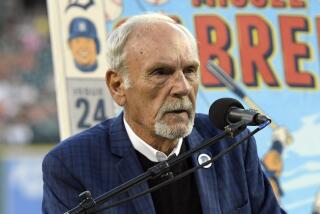

BALTIMORE — Ever since Jim Palmer started his comeback, not a day goes by without someone asking Scott McGregor if he’s planning one of his own. McGregor smiles, but his answer is always the same. Something along the lines of, “Nah, you wouldn’t want me back.”

The truth is, McGregor doesn’t want to come back. It’s fine with him if two former teammates, Palmer and Mike Flanagan, attempt to recreate their glory days with the Orioles. But that part of his life is over. The new part -- the part he always promised -- has just begun.

McGregor, 37, is the youth pastor of the charismatic Rock Church in Towson, Md. His schedule, a whirlwind of counseling sessions, youth-group meetings and Bible classes, leaves him little free time. Why, McGregor is even the coach of the academy’s baseball team.

As he said toward the end of his career, it’s his calling. How ironic that such talk once made him an object of ridicule. The Orioles’ general manager then, Hank Peters, openly questioned his dedication. On bad nights, fans would yell, “Where’s your God now?”

Today, McGregor refers to those final chapters -- those intense personal struggles of 1987 and ’88 -- as the most valuable period of his life. It taught him rejection, an experience necessary for his later work. And it enabled him to recognize his baseball career was over.

That, in turn, led to criticism of a different kind. After 138 wins, McGregor had nearly two years left on a four-year, $4 million contract when he was released with an 0-3 record and 8.83 ERA on May 2, 1988. The Orioles wouldn’t dare let him pitch again before 50,000 skeptics assembled for Fantastic Fans Night.

Snicker if you must at McGregor and his strong beliefs; the simple fact is, he’s come to terms with his retirement. Palmer, 45, can hardly say the same. Flanagan, 39, is another story entirely. His comeback this spring is from arm trouble, not inactivity.

“Totally different,” McGregor says. “He hasn’t really left. God, he could pitch another five years, being a left-hander. You never know, as strong as he is. He’s a bull. I would certainly enjoy watching him pitch again.”

As for Palmer, McGregor seems as confused as the rest of us. “Even last year, every time I’d go to the ballpark, he’d be there in Docksiders, khaki pants and his blue blazer playing catch,” he says. “It’s like they say: ‘They can retire your number, but they can’t retire your heart.’ ”

McGregor doesn’t pass judgment; he’s pulling for both players, and chuckles in anticipation of “the major power struggle of the century” between Palmer and Orioles manager Frank Robinson. His own career, meanwhile, seems so long ago. So far away.

Not that McGregor didn’t relish every moment; his office at the academy is filled with memories. Once it was a changing room to a nursery. Now there are photographs of No. 16 with presidents Reagan and Bush. And inside his desk, his favorite Scott McGregor baseball cards.

McGregor says he still loves the game, still loves going to Memorial Stadium. In fact, he has four season tickets in Section 3. “It’s my therapy,” he says. “That’s how I unwind.” His days, to be sure, are not easy. All his life he was coddled. Now he’s the coddler.

“As far as I’m concerned, what I’m doing now is much more challenging than baseball,” he says. “There are times I’ve messed up and thought I’d go back, it’s a lot easier. But now I’ve been given responsibility over teen-agers, their families. Athletes think they’re in such demand. This is much more demanding.”

He knew it would come to this, almost from the moment he became a born-again Christian in 1979. To this day, his critics insist his church activity accelerated his baseball demise. McGregor wasn’t sure then, and he isn’t sure now.

Does it really matter? “I know I wasn’t perfect,” McGregor says, but like most burning issues, this one diminishes with time. For now, he’s most concerned with the present, with helping those kids. In the future, he might even pioneer his own Rock Church.

“That would be the ultimate challenge - it would squash the ’83 World Series,” he says. “There’s a progression of life, always building to greater things. Looking back, that was great. But what I’m doing now, it just blows that away.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.