He Hopes Not to Leave His Mark on Presidents’ Papers

- Share via

James A. Corwin got a letter from George Washington the other day.

It was a simple one-page note. But it spoke eloquently about 200 years of rough treatment at the hands of historians and it cried out for Corwin’s help.

The letter was delivered to the right man: Corwin is an expert at repairing the frayed remnants of historical figures.

These days, every day is Presidents’ Day for Corwin. He is principal manuscript conservator for the Huntington Library in San Marino, where he has begun a major preservation effort for the papers of George Washington and Abraham Lincoln.

The library’s famous collection--started in 1919 by railroad tycoon Henry Huntington--contains 450 documents signed by Washington and more than 250 items signed by Lincoln.

The collection draws scholars from all over the world seeking a hands-on feel for the two American presidents’ words. But that personal touch, along with the ravages of time, are leaving many documents brittle and torn.

“The greatest damage to documents is from people simply handling them,” said Corwin, 36, of San Dimas. Exposure to air and light also causes deterioration. So can modern inventions such as ballpoint pens, adhesive tape, plastic binder covers and metal paper clips.

Corwin and assistant Susan Rogers, 38, of Altadena are methodically examining each Washington and Lincoln document and making repairs when needed. Their goal is to make their work invisible.

The Washington letter was a real challenge.

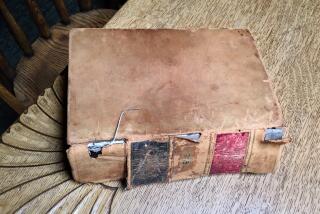

Dated Aug. 31, 1792, it was written as a letter of reference on a large sheet of paper that was folded and sealed with a glob of wax.

“This one is torn in several places and worn through. It needs patching where the missing piece has been pulled away. It should be reinforced along its fold,” Corwin said as he studied the letter over a special filtered light table.

Patching and reinforcing work is done with a durable Japanese tissue paper made from shrubs and tree bark, he said. It is glued to the damaged document with a non-staining, non-shrinkable mixture made from zin shofu , a Japanese wheat starch. Industrial chemicals are used to remove damaging adhesive from the old documents. A household misting device restores moisture to dried-out, crumbling paper.

Corwin said everything he does to documents is reversable, which means future conservators can remove his patchwork if new techniques are developed to preserve old paper.

“We do repairs, not restoration,” he said. “Our work is not to make something look bright and clean. We never do a treatment to make something look prettier.”

For that reason, Corwin decided not to do a thing to a Lincoln-signed copy of the Emancipation Proclamation brought into his office the other day by John H. Rhodehamel, the Huntington’s archivist of American historical manuscripts.

The historic 1862 document, which ordered the freeing of slaves, was smudged along its edges. Its printed text and distinctive Lincoln signature were clearly legible. The paper was not torn or frayed.

Although representative presidential documents are kept on public display in the library, about 15 scholars each year seek permission to do hands-on research with Lincoln and Washington papers, Rhodehamel said.

One of them, Paul Zall, a retired Cal State Los Angeles professor, relied on the library’s collection when he wrote two books about presidential jokes and one-liners: “Abraham Lincoln Laughing” and “George Washington Laughing.”

“It’s hard to articulate what it’s like to work with these materials,” Zall said. “You get all tingly. It’s almost euphoric to think you’re holding something Lincoln held. On the other hand, it scares the bejabbers out of you. Especially when you stand up and little flakes of paper fall off.”

Corwin said he feels the same excitement when he examines a prized letter or important document.

One of the papers he recently worked on was an April 11, 1865, note written by Lincoln to his personal bodyguard, giving the man the night off on the day Lincoln made his fatal visit to Ford’s Theatre.

“You don’t want to think of them as relics,” he said of such documents.

“If you do, you get awfully nervous. But I’ve never made a mistake I couldn’t fix.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.