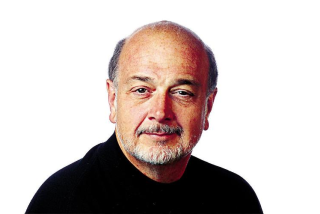

Art Seidenbaum; Times Columnist, Writer and Editor

- Share via

Art Seidenbaum, columnist, editor, writer and wry observer of the Los Angeles cultural, literary and political scenes for nearly 30 years, died Tuesday afternoon.

The editor of The Times’ Opinion section and local Emmy award winner--whose flair for the art of conversation and penchant for puns made him one of the most delightful personalities at this newspaper--was 60. He had been diagnosed as having cancer earlier this year and died at his home in West Los Angeles.

Shelby Coffey III, editor and executive vice president of The Times, reflected that “Art Seidenbaum had a range of interests--from the highly intellectual to the intricately whimsical--rare in journalism.

“He was a writer of uncommon zest and an editor with a sure and steady hand. He brought an enthusiastic discipline to his work at The Times and his many contributions over three decades made it a better paper.”

Seidenbaum, first as a reporter and correspondent for the Saturday Evening Post and Life magazine and later as columnist, book editor and Opinion editor for The Times, dealt with what he once described as “the whole living experience in Los Angeles . . . the problems, the joys and the sociological style that set this city apart. . . .”

But that was a lofty, formal description he had provided for an official company biography, one that was much more solemn than its author.

In person he was more prankster than pundit--a lover of language who delighted in twisting the King’s English into ribald ripostes more suited to the streets of his native New York City than to the hallowed halls of Harvard where he became a graduate student majoring in English after graduating from Northwestern University in 1951.

Later he became a Naval air officer who then wrote about aviation for Life before becoming a cultural columnist for The Times in 1962.

“I knew as little about culture as I did about aviation,” he allowed.

But he did know enough to stay at home with his musings in those early years. “I’m a gregarious animal and I’d spend too much time around the coffee machine,” had he written from the office.

He kept his phone number listed and his thrice-weekly columns reflected an odd blend of cultural events, domestic travails and the reflections of strangers who took advantage of his availability.

“I choose subjects by personal adrenaline--what happens to be bothering me,” he said.

In 1966 he became even more visible as the moderator of “City Watchers,” a weekly one-hour program broadcast until 1976 over KCET-TV. The show was an examination of Los Angeles from films to flimflam and generally included guest experts in diverse fields. He and his co-host, Times arts editor Charles Champlin, were awarded Emmys in 1972.

In 1978 Seidenbaum (pronounced Sigh-den-bohm, he would explain patiently) became editor of The Times’ book review section, a job that brought him into closer touch with his literary pals across the country.

Book editors, or “book beggars” as he liked to call them, devote their lives to hiring great minds for relatively little pay who then spend hours critiquing current literary offerings.

He performed a similar function with Opinion, seeking the thoughts of politicians, sociologists and international affairs experts on topics of the day.

It was that job he held until he was victimized by cancer.

The Seidenbaum legend at The Times, however, extended far beyond his professional capabilities.

Secretaries learned not to remove shoes from weary feet and walk away from their desks, for he was a master at hiding one--it was always one--in an obscure file cabinet. Those who liked to bring their lunch learned not to leave it lying about--sandwiches and apples could vanish for days at a time. Phones at various editors’ desks would ring and it would be several minutes before they recognized the heavily accented voice on the other end offering absurd advice or complaining about the paper’s policies as that of their devious colleague. Writers in his vicinity learned to shut off their word processors before leaving their desks to prevent him from sending nonsensical messages across the building under their names.

And visitors to the Times building--be they presidents or publicists--often found themselves choking on their official lunches after a Seidenbaum pun had cackled across the table.

He would readdress press releases to colleagues who would understand them least. Women whose children had long since grown up would get information on child-bearing classes. Science writers would get invitations to art showings and art critics to science lectures.

One of his favored ploys was to take a manuscript of several hundred pages and deposit it on an aide’s desk as the noon hour neared. He would then quickly walk away saying he “needed a one-paragraph abstract by early this afternoon.”

His own published manuscripts ran a gamut from the coffee-table epic “Los Angeles 200: A Bicentennial Celebration” with pictures by Times photographer John Malmin to “Confrontation on Campus,” a collection of articles about California colleges.

More in keeping with the airy Seidenbaum style, however, was “This Is California--Please Keep Out,” a defense of his adopted state in which he allowed that California needn’t be taken so seriously and that Easterners shouldn’t be so judgmental as they pondered why their children preferred to live Out West.

“The great lesson we’ve learned in California,” he wrote, “is the danger of being locked in and the promise of staying in motion. In California, the going itself is good.”

Before he fell ill, he had been planning yet another book on his beloved West.

Seidenbaum’s longtime secretary, Priscilla Hansen, said he answered every phone call, letter and message that came to his desk. Friends he hadn’t seen since elementary school kept in touch as did the literary lights of the nation for whom he became both editor and congenial companion.

And he was in constant demand as a speaker, not just for what he had to say but for his pixilated prose.

Seidenbaum received awards from groups ranging from Loyola Marymount University to the American Psychological Assn. to the American Society of Landscape Architects to his Emmy, and was embarrassed by each. He also taught, sharing his askant view of life in classrooms at UCLA, Immaculate Heart College, USC and Cal State Dominguez Hills.

Survivors include his wife, Patricia; three sons, Kyle Seidenbaum and Paul and Thomas White, and two daughters, Kerry Ken-Cairn and Janet White.

There will be no services, at his request. A celebration of his life is pending.

The family asks contributions in Seidenbaum’s name to The Tree People, Las Familias del Pueblo or Maryvale, the orphanage.

A FRIEND REMEMBERED: Charles Champlin recalls the active, eclectic voice of an old friend. F1.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.