You Should Be So Lucky as to Have a Worker Like Tina

The van drops Tina Keller off in front of the Pizza Hut restaurant at exactly 9:20 Monday morning.

Tina is eager to get to work, as she always is, but after two days off maybe it’s showing a bit more than usual. She practically skips to the front door.

Starting time is 9:30.

“I’m a very good worker!” Tina says as she bounds out of the bathroom, where she has changed into her Pizza Hut red-and-white-striped shirt, her Pizza Hut apron, and her red Pizza Hut visor.

She gives me a thumbs-up sign.

Tina Keller, 27 years old, is autistic and mildly retarded. She has worked at Pizza Hut in Huntington Beach for four years. She loves her job.

“I work from 9:30 to 1:30, but maybe I punch in a little early,” Tina says. She pulls out a scrap of paper that shows she has clocked in at 9:24, not including the time she has changed into her uniform.

It is still not 9:30. Tina is removing plates from the salad bar, the first of her chores. She rattles them all off: preparing the salad bar, sweeping and mopping the floor, cleaning the bathrooms, helping with the lunch-time preparation.

She is very happy. Her smile spreads nearly to her ears.

“I like to start a little early,” Tina says, “to get everything done.”

She gives me another thumbs-up sign.

This morning, there are more people than usual in the restaurant an hour and a half before opening time.

Pizza Hut’s California human resource manager is here, as is the company’s area manager for Orange and Los Angeles counties and the program manager for the Systematic Training for Employment Program, or STEP, part of a private company in Santa Ana that acts as a liaison for businesses wishing to hire handicapped people. They are here to talk about Tina, of whom they are very proud.

In 1985, Pizza Hut started a pilot program in Orange County to hire people with severe disabilities. It went well. Now the company calls it “Jobs Plus,” and it’s permanent at Pizza Huts throughout the country. The government helps out with grants.

Nationwide, Pizza Hut has hired almost 3,000 severely disabled employees--out of a company total of 68,000--and plans to hire more. The company’s employee turnover rate, depending on the region, ranges from 150% to 250%. For disabled employees, it’s just over 28%.

Programs such as STEP--whose clients include Carl’s Jr., Taco Bell, Pepsico and Hoag Hospital among others--help with training and to forestall potential problems with the handicapped employees and those who will work with them.

Pizza Hut, one of the biggest boosters of the idea, says it likes the enthusiasm of its disabled employees, their dependability, their willingness to learn.

“We’ve found that our customers have been educated, too,” says John Walker, the company’s human resource manager. “Seeing a handicapped person on the job has helped change the public mindset away from the idea that these people just need to be taken care of someplace as opposed to, ‘Let’s get them out there, working.’ They’ve got responsibilities.”

And for Tina, adds Diane Sabiston, the STEP manager, a job means stability and a sense of purpose.

“Tina has very severe behavioral challenges,” she says. “But she knows what she has to do to keep her job. . . . Sometimes at the home where she lives, she’ll lash out, get upset. I’ll say, ‘Tina, why don’t you do that at work?’ And she says, ‘But I love my job and I want to keep it.’ ”

So everybody seems pleased. Especially Tina.

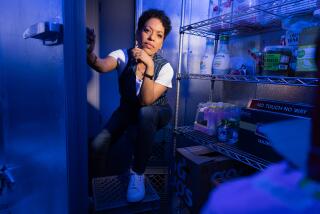

Now she has moved behind the counter. She opens a refrigerator and places containers of vegetables, fruits, cheeses and salad dressings on a tray and carries it into a back room.

“I’m strong!” she says.

Tina washes her hands. That’s what the sign above the faucet says to do--wash your hands. Tina does this a lot. Then another employee enters the room.

“I’m going to be in the paper,” Tina tells her. “And I want a picture!”

Tina opens the containers of food and inspects the contents. She throws out anything that is not up to muster, like the discolored grapes, or the mushy cherry tomatoes, or the grated cheese near the bottom of a large bin.

“It’s going bad,” she says of the cheese. “When it has an odor, it’s going bad. Only put the good stuff out.”

The salad bar is Tina’s responsibility. She monitors it during her shift. Things run low, Tina resupplies. It’s all on her shoulders.

“I make my own decisions,” she says, then smiles. “Except on the night shift. Because I don’t work then.”

There’s a printed sign with the Pizza Hut logo above the door leading from the back room to the counter area.

It reads in part: “The LA/Orange District Vision is to provide our customers with quality products, quick service and a clean, friendly environment through flawless execution of our system. We believe our customers to be guests in our ‘home’ and will treat them to a ‘family’ experience.’ ”

I ask Tina if she knows what the sign says.

“I haven’t really read it,” she says. “I just try to get the work done. You see, work comes first.”

Tina says that when she first started working here, her chores weren’t such a breeze. There was a lot to remember.

“It’s easier now. I really like it. I always want to stay with Pizza Hut. I make good money. I get a free meal. I get along with my friends here. I have a good time working with Pizza Hut.”

Her co-workers agree.

Santiago Vargas, who’s been working here eight months, says Tina works hard “and she never gets mad.” Others treat her with smiles and, seemingly, their respect.

Tina says that she forgets how much she makes ($4.45 an hour, or $89 for her 20-hour week), but her wages pay about half her rent at the Anaheim residential facility where she lives.

She’s also bought a CD player, a television, a VCR and the furniture in her room. Her weakness is clothes. She must get permission before she can buy any more.

It is people like Tina Keller that the Americans With Disabilities Act, expected to be signed by President Bush soon, is meant to help. The legislation, which will guarantee about 43 million disabled people the same job rights as other Americans, is being hailed as the greatest advance against discrimination since the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The bill sailed through Congress. Only a handful of conservatives--among them Orange County Reps. William E. Dannemeyer and Ron Packard--voted against it, calling it a “nightmare” that unfairly burdens employers. Companies with fewer than 15 employees are exempt from the bill’s provisions.

But Tina doesn’t know about any of that. Her world is much smaller.

She has her job, her friends, the weekend visits with her parents. Her sister, who lives with her husband in Arizona, just bought a new car.

As for herself, marriage isn’t in the plans. “No, uh-uh, I don’t like boys. Not for me. Sorry about that.”

Just before leaving the restaurant, I stop Tina as she’s mopping the floor--to say goodby.

“How am I doing?” she asks. “Great,” I tell her.

Tina gives me a thumbs-up.

“Pizza Hut!” she says. “I want to stay!”

Then she smiles. Up to her ears.

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.