He Knew His Place on Mets

- Share via

NEW YORK — Gregg Jefferies never saw anything particularly difficult about hitting the curveball whether big league, Little League, high school or sandlot. That was just the trouble.

There is a protocol to be observed in Baseball with a capital B and it doesn’t include rookies making their presence--or opinions--felt.

Baseball is a little like the House of Lords or any other venerable congress of men. Tradition is very big in Baseball, where dignity is prized and deviation therefrom is treated with scorn. The terms hotdog and showboat are not terms of endearment in the grand old game.

The trouble with Gregg Jefferies was not that he was flashy or loud. In fact, he was kind of grumpy. He didn’t get his name in the paper too much. It was just that he was . . . well, he was good and he knew it. That can be most irritating of all.

Humility might get you buried in Hollywood, but it goes a long way in baseball.

Jefferies wasn’t cocky exactly, just not deferential. Rookies are supposed to tug at their forelocks, smile bashfully and say, “Aw, shucks!” a lot.

Jefferies never got the message. It was hard to put a finger on precisely what he did wrong, but it definitely wasn’t a rookie attitude. For instance, throwing the helmet. Coming down the dugout steps raging. This is all right if you’re Stan Musial or Kirk Gibson or, say, a Will or Jack Clark. Someone who’s been around. Someone whose picture is already on the clubhouse wall. They don’t haze rookies any more--make them carry the bat bags or send them out for left-handed monkey wrenches. That stuff went out with the Ruth Yankees. But rookies are still supposed to know their place.

Some New York Mets thought it amusing when Gregg Jefferies brought his veteran’s temperament to the club. “He was 21 and he acted as if he had won three batting championships,” Keith Hernandez once observed with a grin.

Of course, Jefferies’ self-esteem was not all that hard to understand. He led practically every league he ever played in. His batting swing was equal parts pancake syrup and butter. Whenever he played what amounted to a full season, he batted numbers like .354 and .367. He was a switch-hitter and seemed to bang the ball with equal skill and enthusiasm from either side of the plate. If he had a weakness, four leagues and 200 pitchers hadn’t found it. He hit .464 in high school, he was the Appalachian League’s player of the year, the Texas League’s most valuable player and the minor league player of the year in 1986. It wasn’t a career, it was a parade.

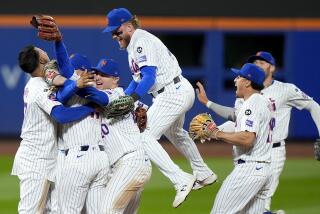

The New York Mets, of course, are not a set of contemplative monks. Before they broke them up, they were a team of grizzled, successful, seasoned star performers like Gary Carter, Keith Hernandez, Howard Johnson and Kevin McReynolds. If anyone was going to throw bats or helmets, it was going to be they.

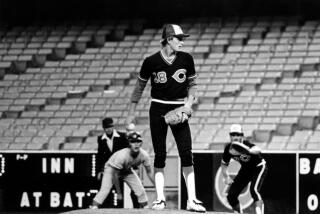

There was a pitcher named Roger McDowell whom New York adored. He was a reliever who appeared in 75 games during the pennant year and consistently racked up 23, 25 and 22 saves a year. Him, Gregg Jefferies got in a fistfight with. Not since the young Leo Durocher spiked Ty Cobb had there been a rookie this brash.

Jefferies never did master the art of forelock-tugging, or of laying his helmet carefully in the rack after taking a third strike and murmuring, “Son of a gun! He got me with a good pitch!”

He doesn’t act like the butler. But he has stopped reacting to misfortune as if the gods had it in for him and they had a lousy nerve.

It’s not that he has anything to be modest about. Gregg Jefferies is batting .315. He is among the league leaders in hits (83 makes him ninth), extra-base hits (31) and runs scored (47), and he is tied for the league lead in doubles (21).

The other afternoon at Shea Stadium, he scored the winning run for the Mets in a ninth-inning rally against--guess who?--Roger McDowell, now pitching for the rival Philadelphia Phillies.

Was there any personal gratification in getting a key hit and scoring the winning run against--of all people--his old fistic adversary, Roger McDowell? the press wanted to know.

The old Gregg Jefferies (he’s 22 now), might have grinned wickedly or nodded his head emphatically. The 1990 Gregg Jefferies just looked cautious--and serious. “No, no! That’s all forgotten,” he insisted. “Roger is a class guy and a fine pitcher with good stuff. We just got away with one.”

What kind of a pitch did he hit? “I never divulge pitches,” Jefferies shot back. “I might want it again.” But doesn’t the pitcher know? he was asked. “The rest of the league doesn’t,” Jefferies retorted.

He’s not completely un-arrogant. The new Jefferies earlier hit a home run (his 10th) and a single in that game and drove in three and scored two of the Mets’ six runs. “This game is fun again. Winning is fun and it brings you closer together,” Jefferies explained to the media clustered around his locker after the game.

Of course, if the Mets win the pennant, Gregg Scott Jefferies of the San Mateo Jefferies can kick all the water coolers and punch all the helmets he wants. But now, as an elder statesman and No. 3 batter on a pennant-contending team, Gregg may frown on rookie tantrums himself and may be expected to take any offending youngster aside and say, “Son, save those till you beat the Phillies with a few ninth-inning rallies or put your team in the playoffs. Things go better that way. Believe me, I know.”

Or he can say as Casey Stengel once said to another rookie: “As soon as that water cooler develops the curveball that got you out, it’s OK to go over and kick it.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.