APPRECIATIONS : The One-Man Variety Show Named Sammy Davis Jr.

There have been a lot of balladeers, a lot of dancers, a lot of clowns, a lot of mimics, a lot of actors who could do both comedy and the heavy stuff. But no one comes to mind who was all of those talents to such a superlative degree as Sammy Davis Jr., who on Wednesday lost his brave battle with throat cancer.

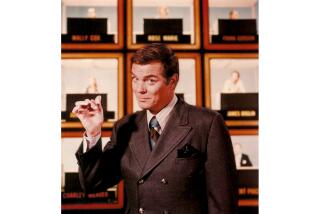

He was a one-man variety show, every act on the damnedest vaudeville bill anybody ever watched. He was all the floats in the big parade, a cast of hundreds (it sometimes seemed) contained in one slight frame that had to be composed entirely of pure genius and pure energy.

It was not just that Sammy Davis Jr. could do so many different things; it was that he did them all so amazingly well. In the space of half an hour he could make you think of everybody from Bojangles Robinson and Al Jolson to Nat Cole, to cite only a few from a whole galaxy of audience-holding entertainers whose equal he was.

At the start of the ‘60s, one of the best reasons anybody had for going to Las Vegas was to catch what came to be called the Rat Pack: Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Peter Lawford and Sammy. Their appearance at the Sands Hotel was the toughest ticket in town.

Considered historically, it might be that their high jinks and their heavy joshing would be found a bit self-indulgent and even self-conscious, a kind of every-night boys’ night out. But the saving grace was that Frank and Dean and Sammy were talented and charismatic performers who, as ballplayers say of a fast pitcher, could really bring it. If there was anything to forgive, you forgave it when the singing started.

Sammy’s role was as the mascot of the group, and the kidding was (so my own memory says) not always comfortable for the audience and possibly not always comfortable for him. But the role was also a bit of a disguise, like the rube who turns out to be the real pool shark. When the stage was his, he knocked the audience sideways, and it became wonderfully clear that the honors, talentwise, were equally divided up there.

(It’s hard now to remember exactly what Lawford’s function was in the free-for-alls: a kind of bemused charm, I guess. The sadness about him was yet to come.)

The gifts and the magical stage presence that Sammy Davis Jr. had were honed and polished in a hard school that began for him at an age when most of his contemporaries were still wearing diapers at night. As he wrote in a couple of notably candid and moving autobiographies, he spent years trouping when a good audience was one that let you get off stage uninjured; years when, talented or not, he was handcuffed to Jim Crow.

Even in Las Vegas in the times of his first triumphs, the color line separated the stage from the lounges and the tables like an iron curtain, to keep the high-rollers content. Over there in Las Vegas, and among black entertainers, one of the things Davis will be remembered for most gratefully was his role (with Sinatra’s help) in breaking down the color line.

Thanks to his own candor about himself, Davis’ life was widely known to be a kind of cautionary tale, a three-act play divided into the rise to fame, the costs of fame and, at last, the rewards of fame. He left no doubt that he hadn’t handled success well. He had worked hard and for a time he enjoyed hard, making a mess of things until he got his act together again (with some chastening help from Sinatra).

What kind of fool was he? His own kind, but the point the world could note at last was that he stopped playing the fool and revealed the strength that had got him past all the earlier hazards, including the wreck that cost him an eye and nearly his life.

The rallying around him when he fell ill said a good deal about Sammy Davis Jr. His talent had spoken for itself; his kindness and his humanity revealed themselves in the loyalty of his friends.