First Measles Death in County Is Confirmed : Epidemic: Second vaccinations are being urged for children as the county records 625 confirmed or probable cases of the disease this year.

- Share via

An autopsy has confirmed that measles killed a 10-year-old San Diego boy in February, making him the first county resident to die in an epidemic that has intensified over the last two months.

Blood test results this week confirmed that Hector Lopez had measles, and not some other disease that might have contributed to his Feb. 22 death, Deputy Coroner Robert Engel said Friday. The cause of death is listed as measles, with complications from inflammation of the heart.

By the middle of this week, 625 confirmed or probable cases of measles had been recorded in San Diego County this year, said county public health officer Dr. Donald Ramras.

That is nearly 40% higher than occurred in 1982, the last year in which there was a significant outbreak.

County and state public health officials say they know what they would do to stop San Diego County’s epidemic if they had the money:

- Give a second dose of measles vaccine to every schoolchild who hasn’t had two doses and perhaps also to every child entering junior high or college this year.

- Conduct aggressive immunization campaigns in low-income communities.

- Hold mass-immunization clinics in schools and other community locations.

- Open public health clinics at night and on weekends for immunizations.

“There’s absolutely no question a second dose should be done. None,” said Ramras. “Our advice that we give is based on what we think is best for San Diego. But what we, the health department, can offer to the people who come to us is predicated on what we get through the state.”

But even $5.8 million more for the entire state, approved Wednesday by the governor, will not allow such steps to be taken, said John Dunajski, assistant chief of the California immunization program.

The extra money will barely cover what had been an expected shortfall of funds for first-dose measles vaccine, Dunajski said.

The state, under a federal program, provides low-cost measles vaccine to counties. But the number of doses subsidized through this federal effort has stayed the same, even as demand has increased. The federal government, though recommending the second dose, only provides the low-cost vaccine for first doses.

In Dallas, where 1,931 cases of measles have occurred so far this year, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control is sponsoring a massive immunization project today at 19 sites.

In San Diego, county health clinics, strapped by years of funding shortages, give immunizations only a few hours a week, and no special immunization hours are planned.

Instead, public health nurses have concentrated on quick investigations of every suspected measles case, said Sandy Ross, immunization project coordinator for the county.

The investigators give isolation instructions to family and friends if they begin showing symptoms. Exposed people also may be given vaccine or immune globulin shots to prevent or minimize cases that do arise.

In some schools and day-care centers, children who are considered susceptible to measles have been excluded from school for two weeks, at the health department’s request, when a measles case crops up in a classroom, Ross added.

Public health officials say they are painfully aware that these steps don’t address the real reasons for measles’ spread--unimmunized preschoolers and older children whose first dose of measles vaccine did not work.

Ross noted that the Lopez boy who died was one of the children whose earlier vaccine had failed.

The U.S. Public Health Service issued guidelines in December recommending a second measles vaccine for children just before they enter school, for all students entering college and for all medical personnel.

The recommendation was issued in hopes of preventing the 35% to 40% of measles cases affecting persons older than 5 years in whom a first dose did not result in immunity, the health service said.

However, there are no plans in San Diego County to inoculate all entering kindergartners a second time against measles because there is no money to do it, Ramras said. He said it would cost $700,000 for vaccine to do that countywide.

Statewide, it would cost at least $5 million just for the vaccine to inoculate kindergartners and college freshmen, Dunajski said.

Ramras concedes that it isn’t much comfort turning the issue of whether to get a second measles vaccination over to parents, since the inoculations are expensive.

Just buying the vaccine itself to give shots to his three teen-age and young adult children cost $75, Ramras said. At a private doctor’s office, a shot costs $30 to $40, and many insurance policies don’t cover the cost.

If the usual annual cycle holds, the number of new measles cases will taper off as the year progresses and then pick up again next winter.

In the meantime, because the most serious measles cases often occur in babies, health officials are recommending that infants be immunized at 12 months, three months earlier than usual. But early immunization increases the chance that the child won’t have permanent immunity, so a second shot between ages 4 and 6 would be necessary.

Because of the San Diego outbreak, parents might want to ask their doctors about inoculating babies as young as 6 months, Ramras said. Such children would need a second shot at 15 months and again at school age.

Older children who never received a second MMR (measles, mumps and rubella) shot also should receive a second dose--even if they are past their teen-age years. Anyone born after 1957 is considered at risk, because of problems with the early vaccine.

Measles begins with cold symptoms and progresses to a high fever and a severe rash. Complications can include dehydration, pneumonia, ear infection and encephalitis. Encephalitis can leave permanent brain damage.

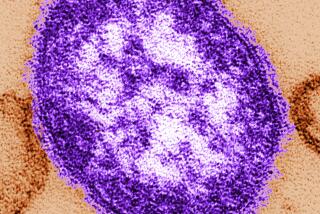

The measles virus is spread through the air, even as long as an hour after the infected person has left a room. It also can be spread before the infected person is aware of having the disease. This makes it particularly important for parents to leave uninfected children at home when going to doctors’ offices or an emergency room, health officials say.

Southern California has had a measles outbreak since 1987, but San Diego’s did not take hold until last year. Los Angeles officials had recorded 1,407 measles cases and six deaths by the end of March.

On Friday, there were four children in Children’s Hospital in San Diego because of measles complications, including one infant who has been on life-support equipment for nearly three months.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.