Convicted Mercy Killer Finds a Safe Haven Behind Prison Walls

- Share via

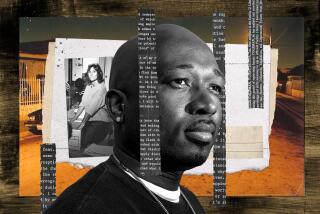

STILLWATER, Minn. — On the eve of his imprisonment for the mercy killing of his diseased and bedridden wife, Oscar Whelem Carlson begged God to strike him dead.

“I was so afraid that I prayed that night that I could have a heart attack and die,” Carlson said. “I was at my lowest.”

The 79-year-old retired dairy farmer and former bus driver said he was petrified at the thought of living in a maximum-security penitentiary with rapists, thieves, drug dealers and killers.

He was at peace with his earlier decision to pump four bullets into his wife of 47 years, Agnes. But he had hoped for a more lenient sentence than 3 1/2 years at Minnesota’s Stillwater Prison.

About halfway into his stay, Carlson is delighted with the place.

If he could draw an occasional furlough to visit his wife’s grave in Evansville, he said, he wouldn’t mind making the prison his permanent home.

“I’d much sooner stay here than in an old folks’ home,” said the bespectacled Carlson, who shares laughs and meals with convicted felons one-fourth his age. “Agnes was in that nursing home and she didn’t like it there one day.”

Carlson said many of his fellow inmates aren’t aware of his past. But when they ask questions, he doesn’t hesitate to answer.

“I talk to them like I was one of the boys and they treat me that way,” Carlson said.

Prison caseworker Glenn Hall said Carlson is a refreshing prison oddity: a secure, gentle man who adores his job as caretaker of a prison garden brimming with melons, tomatoes, corn and other crops.

“They all kind of treat him like a grandpa,” Hall said. “Even I do in a way.”

Carlson spent his first 11 months in the “big house” before getting a bed March 20 in a minimum-security building just outside the prison walls. With credit for good behavior, he could be released in September.

Carlson said he didn’t seek the transfer and actually missed the maximum-security unit for its assortment of religious services. He grew up Lutheran, but participated in spiritual gatherings of all sorts and had befriended a Roman Catholic priest.

Marcene Cole of Fergus Falls, Carlson’s oldest daughter, said she was surprised at the speed of her father’s adjustment.

“I think he was awfully scared at first,” Cole said. “But he made the best of it. He seems to look at things positively.”

Bill Schroeder, Carlson’s longtime friend, said prison may have been a blessing in disguise because many people in the Evansville area would have shunned Carlson had he been ordered instead to do community service.

Carlson said Cole and his younger daughter, Millie, supported his decision. But he said his other daughter, Mary Beth, was angered that her mother’s life--albeit miserable at times--was cut short. She refused to discuss the ordeal.

“I wasn’t too happy at first,” said Schroeder. “I was really shocked and really angry with him. It took me quite a while to get myself together on this to realize that Oscar was at his breaking point. Everybody has a breaking point.”

For Carlson the breaking point arrived when he received word from a hospital in Alexandria that Agnes would have to undergo hip surgery.

“That’s when my mind slipped and I got my gun,” Carlson said.

Carlson retrieved the weapon from his woodshed, drove to the nursing home and prayed before asking his wife if she wanted to have the surgery done.

When she said no, Carlson said he asked her if she wanted a “shot”--a term she understood from his days as a butcher when he used the revolver to kill pigs and cattle.

“She looked right at me and she said, ‘Yes.’ ” Carlson said. “I shot her twice in the heart. She knew I was pretty handy with the gun.”

Seeing her mouth open and fearing doctors would rush in and attempt to revive her, Carlson said he shot her again--once in the eye and once in the mouth. Before sheriff’s deputies arrived about 20 minutes later, Carlson said, he wept and prayed over his wife’s body.

Asked by Douglas County District Judge Paul Ballard why he killed her, Carlson said, “Because she was suffering and I couldn’t stand to see her suffer any longer.”

He said his only regret about Agnes was placing her in the nursing home in the first place. But Alzheimer’s disease had warped her mind, he said, and he was weary from providing 24-hour care.

Although the Carlsons’ rural Evansville house had indoor plumbing, Agnes began insisting on using the outhouse, and Carlson said he had to accompany her to prevent her from wandering away. She had long since started to believe that Carlson was her father and she often didn’t recognize her children, Carlson said. In addition, the vegetable garden that had been the centerpiece of their lives had gone to weeds.

Inside the nursing home, Carlson said, Agnes took a turn for the worse. She had been there about 10 months before he killed her.

“I wouldn’t care to stay in that place any more than she did,” Carlson said. “They called it murder, what I did. But she very much agreed on it so I think I helped her out of a lot of mess.”

Although Carlson enjoyed maximum security, he said minimum security provides for group outings that allow him to bowl, attend Sunday religious services in Stillwater and shop.

Better yet, the spry Carlson can tend to the prison’s half-acre garden, situated near the prison golf course. Carlson said he works from 7:30 a.m. until 11 a.m., breaks for a 90-minute lunch, and ends his day in the garden at 3 p.m.

“We got bankers’ hours,” he said.

Despite being well-liked, Carlson said he hasn’t made any close friends in minimum security because “they come and go too soon.”

But he said three strangers have written to him to offer their companionship upon his release. The most serious offer came from a 73-year-old Florida woman who read about his plight and offered to care for him “the rest of my days,” Carlson said.

“It’s a possibility,” he said. “But like they tell me, I’ve got a long time to make up my mind. I’m in no hurry to leave.”

BACKGROUND room where his wife, Agnes, 71, lay suffering from Alzheimer’s disease and a broken hip. He

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.