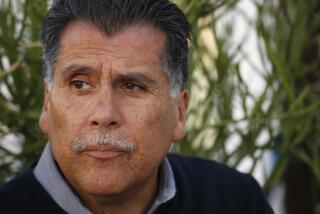

Jim Pruitt Takes Time to Give to His Community

- Share via

For Jim Pruitt, volunteering isn’t voluntary.

“I was raised in a time when there was more of a sense of being obliged to do things for people. I believe in the idea the way President John F. Kennedy said it: ‘And so, my fellow Americans, ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country,’ ” said Pruitt, 68, of Santa Ana.

“If people don’t give back something, then the community will fall apart, and we’ll be in very sad shape. I think younger people have forgotten that. They’re going so fast, they want so much, so many things, they don’t have time to help.”

Pruitt has made time.

He volunteered to pilot bombers in World War II, fight fires in his neighborhood fire department in Orange County and, for the last 23 years, serve the people of Santa Ana as a reserve police officer.

Pruitt retired from the reserves this week. In a ceremony Wednesday, he was honored by the chief of police, the City Council and the County Board of Supervisors for his legacy of service.

“This guy donated 23 years of his life to the community,” said Sgt. Dave Redwine, reserve coordinator for the Santa Ana Police Department.

Pruitt was born and raised in the Midwest--Indianapolis and Detroit. In 1942, he volunteered to fly for the Army Air Corps and piloted a B-24 Liberator bomber on 30 missions over France and Germany, earning a Distinguished Flying Cross for his effort. He volunteered to remain in the Air Force reserves after the war and became a lieutenant colonel before retiring in 1981.

Back from the war, he married and settled in Orange County. He attended Santa Ana College (now Rancho Santiago College) and got a job as a research assistant for Chevron Oil in La Habra, working there until 1983. He built the home in which he and his wife, Daphne, have lived for 35 years in what was then the unincorporated community of Santa Ana Gardens.

Life was great, Pruitt said, but “I needed to find something to fulfill my civic duty.”

He found his calling in the tiny Santa Ana Gardens Volunteer Fire Department.

“This was prior to beepers. We had a post in a field out back with a siren on it. Day or night, 365 days a year, that thing would go off and mothers get your kids out of the way!”

Pruitt fought fires for 10 years before Santa Ana annexed the neighborhood and disbanded the volunteers.

Again, Pruitt said, he felt the nagging need to get involved in some kind of community service.

A friend suggested the police reserves.

“It seemed like an interesting challenge. When people call the police, they need help, and I felt that was something I could do.”

In 1966, at the age of 44, Pruitt donned a police uniform, strapped on a gun and joined regular officers in duties ranging from crowd control to pursuit of fleeing felons.

In those days, the police reserves in Santa Ana was a loosely organized, fledgling organization. “We had no training. They pretty much just sent us out.”

Pruitt said he drew on his wartime experience to help him through the rigors of police action.

“The most important quality of a good police officer is being levelheaded. I learned that overseas. I served with guys who knew what they had to do and quietly went on their way prepared mentally to go out there each day.”

Pruitt worked at least one full patrol shift a week, usually on weekend nights. He frequently was called in the middle of the night to help out.

“No matter what you think it is, when you get out there you find it’s different. You go from can’t-stay-awake (situations) to adrenaline and your hair standing on end.”

Pruitt said he never fired his 9-millimeter semiautomatic pistol on duty, but remembered the tremendous anxiety of going into a darkened building, gun drawn, in search of a burglary suspect, or the struggle to remain calm when he pursued a suspect into a back yard and found himself in the middle of a crowd of 50 people--all relatives of the suspect.

Pruitt learned, too, that some of the toughest moments an officer faces are not the most dangerous.

“By far the worst was family fights. Nothing was ever resolved. You could never leave feeling satisfied you’d accomplished something.”

Pruitt felt that despite the hazards and difficulties of volunteer police work, he was compensated emotionally.

“I loved the sense of belonging to an elite organization. I was proud to be part of it.”

Pruitt’s experience on the street quickly convinced him that if reserve officers were going to perform the same duties as regular officers, they should be trained and held to the same standards.

He instituted screening and training programs for reserve officers. Since 1972, he has been the ranking officer in the 22-member reserves.

“I’ve tried to be a high-visibility head of the reserve corps, representing the interests of the volunteers through the shifting tides of command and reorganization.”

But Pruitt decided that, at 68, he’s feeling the age gap between himself and the officers in the field and that “it’s time to move onto something else.”

He said he and his wife will spend more time traveling in their motor home and that he will be thinking of some other way to help out.

“I’m thinking of a number of things, probably something in the law-and-order area, maybe MADD (Mothers Against Drunk Driving).

“There are so many groups and causes that need people to look after things. I just want to find somewhere I can be effective.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.