Authors Find Inspiration in Imperfection : Two Writers Transform Afflictions Into Novel Characterizations

- Share via

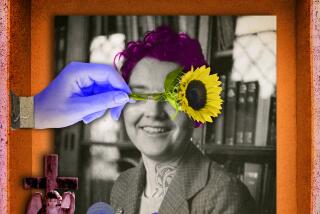

NEW YORK — Lynne Sharon Schwartz has a “lazy” right eye. With both eyes open, her vision is normal. But when she closes her left eye, objects seem to break up, becoming a collection of particles rather than a solid mass.

In a recent interview at her Manhattan apartment, Schwartz, the author of “Rough Strife” and “Disturbances in the Field,” motioned to a couch and explained that the eye enabled her to see around it. She gives the same condition to the character Audrey, her alter ego and the narrator of “Leaving Brooklyn” ($15.95, Houghton Mifflin).

‘Became a Metaphor’

“It became a metaphor for seeing the reality behind the veil, the surface,” Schwartz said. “It’s wonderful for an adolescent. The people around this girl are trying to present the world as safe and happy and decent. She wants to know about all these ugly things and everybody is trying to conceal them.”

Author David Shields, like W. Somerset Maugham and John Updike, is a stutterer. A native of California, he acquired a large vocabulary by learning as many synonyms as possible for words that gave him difficulty.

“Dead Languages” ($18.95, Knopf), his second novel, traces the childhood of Jeremy Zorn, a stutterer growing up in Los Angeles and San Francisco in the 1960s and ‘70s.

“Much of the burden of the book is trying to show how everyone has their own stutter,” Shields said. “Whether they’re the victim of political sloganeering, or whether they fail to communicate their essence or whether they hide behind academic jargon.”

Schwartz and Shields are among the many writers who have used their physical afflictions in a literary way.

--Rudyard Kipling suffered from failing eyesight, and made Dick Heldar go blind in “The Light That Failed.”

--Flannery O’Connor contracted lupus, a crippling disease that eventually killed her. Her short story, “Good Country People,” centers on a teen-age girl with an artificial leg.

--Carson McCullers was in ill health most of her life, the victim of several strokes. “The Ballad of the Sad Cafe” features the cross-eyed Miss Amelia and a hunchback named Lymon Willis.

--Maugham transformed his stuttering to Philip Carey’s club foot in “Of Human Bondage.”

‘Genius of Disease’

In the preface to a collection of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s short novels, Thomas Mann linked the Russian author’s greatness to his epileptic seizures. “I am filled with awe,” Mann wrote, “with a profound, mystic, silence-enjoining awe in the presence of genius of disease and the disease of genius of the type of the afflicted and the possessed in whom saint and criminal are one.”

Mann cited the nihilistic Kirilov in “The Possessed” as an extension of the feelings brought on to Dostoevsky by epilepsy. He insisted that “certain attainments of the soul are impossible without disease.” And he wrote of the “incomparable sense of rapture” and “inner enlightenment” that illness can cause, but also of “horrible depression” and “spiritual ruin.”

Both Schwartz and Shields drew heavily on their own lives. Like her character, Audrey, Schwartz grew up in Brooklyn in the 1940s and used her eyesight to draw a contrast between her seemingly uneventful life and the horrors of the Holocaust and atom bomb.

‘Things Being in Dots’

“You get the idea of things being in dots, that they’re not really together. This translates into the world being unsafe, dangerous, which leads you to all sorts of modernist notions,” she said. “Everything looks compact but actually the atoms are racing around each other. Philosophically and emotionally, that’s what happens to this kid. Things are not as solid or coherent as they seem.”

Shields had articulate parents and remembered his frustration at not being able to match their verbal skills. “I felt like my family was living in language while I was dying in it. That is the key to the whole book. I, too, wanted to be sort of a verbal star. I think what it did was drive me to the written word.”

Audrey and Jeremy must each confront the pain of being “flawed,” damaged goods. Audrey’s parents are horrified by their daughter’s eye, forcing her to wear contact lenses against her will.

“This idea of perfection was very important in Brooklyn,” Schwartz said. “Things should be right, they should be perfect. They didn’t care what was inside. You could have all sorts of moral and emotional flaws, but they liked their children to look right, the girls especially.”

Jeremy’s stuttering leads to humiliating attempts at acting and debating and creates tension with his girlfriends and parents. Shields writes of the twin impulses to be “morally impeccable” and “squeaky clean.”

“It’s never been just a little glitch in my tongue but an entire stripe across my chest that seemed to be my signature of being human,” he said in an interview. “Someone stuttering always seemed to me to be saying life wasn’t perfect and I especially wasn’t perfect. Things were flawed, there was a kind of tragic scratch across everything.”

A Humorous Tone

Much of “Dead Languages” has a humorous tone, and the book gave Shields the chance to express a healthier outlook on stuttering than he was capable of in his own life.

“My own feelings about stuttering are relatively serious,” he said. “It seems to me that the fun and joy of writing is you get to reach a higher plane, some larger human realm. In the whole scheme of things, stuttering is a minor thing. I think Jeremy learns that, kind of.”

While Audrey and Jeremy are each blessed with special insight, their afflictions also create distance between themselves and other people. Schwartz noted that Audrey’s “vision” interferes with her ability to connect emotionally.

“She was aloof from her life, her surroundings. She wants to distance herself, almost look with condescension on the people around her. I wanted to show the ruthlessness and lack of awareness of a precocious adolescence,” the author said.

Audrey is able to “see” a better life than the world of Brooklyn, and has little use for her parents’ everyday existence of card games and gossip. Schwartz attributed this to a lack of insight.

“She sees these people as trite and silly, looks at them like they’re wasting their time. In Brooklyn, people also have lives and passions and conflicts; they live. One life is as good as another. It’s her limitation she can’t see that people of Brooklyn have lives, too.”

Jeremy’s sense of irony, of detached amusement, is so strong that even when his mother dies, he is left numb by the condolence cards, admitting that he wanted “to feel famous feelings but couldn’t get past difficulties in construction.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.