RESCUING THE S&Ls; : Perelman’s Gambit : Texas Bailout Leader Built Empire on Challenges

- Share via

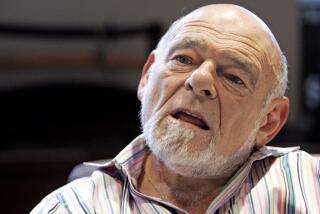

NEW YORK — Financier Ronald O. Perelman has made his first $1 billion proving that he loves taking on troubled companies--particularly in industries he would seem to know nothing about.

In 1983, he bought and began to resurrect Technicolor, the film processing giant that had lost its way. Two years later, he acquired and started rebuilding Revlon, the storied cosmetics firm in dire need of a make-over.

And Wednesday, an investor group led by Perelman said it would put up $315 million to buy five troubled Texas savings and loans, with the help of a $5.1-billion government bailout.

“It all fits into a pattern,” said Andrew Shore, analyst with the Shearson Lehman Hutton investment firm. “Rarely does he go after a business that isn’t in crisis. He seems to need a challenge.”

In pursuit of such challenges, Perelman has erected an empire worth nearly $5 billion over the past decade. Built with his wits and liberal use of high-yield, “junk bond” financing, Perelman’s holdings now include not only the cosmetics giant, but also a drug testing firm, a licorice maker and a cigar manufacturer. His personal fortune is now worth an estimated $1 billion, according to Forbes magazine.

And as Wednesday’s announcement suggests, Perelman wants to build much, much more.

It is the building, he has said, that is key. The abrasive, cigar-loving Perelman first made his name as a corporate takeover artist, in fights for Revlon, razor-maker Gillette, and others. In the view of many observers, he remains one of the most dangerous raiders on the scene.

But as he has acknowledged publicly, he wants to be known instead as a builder--as a corporate manager who improves and expands the companies that come under his control. And some have already been persuaded by his success at turning around Revlon and Technicolor, which he sold last September to Carlton Communications PLC.

“The jury is still out on his managerial abilities,” says Shore. “But he has shown some results, and that’s clearly what he wants to be known for.” Perelman was said to be out of the country and unavailable for interviews Wednesday.

Perelman may have inherited his taste for takeovers.

He worked until he was 35 at his father’s small Philadelphia conglomerate, Belmont Industries. As an apprentice in the family business, he bought or sold several companies, including a galvanizing firm, a shoe manufacturer, and a small, struggling bank.

Ten years ago, he struck out on his own, making a $2-million investment in a jewelry distributor that grew to become his present holdings.

One of his first major purchases was the 1983 acquisition of Technicolor for $125 million. He sold off its consumer photo-processing business, including a chain of one-hour photo processing labs, but kept the commercial photo processing operations, which now are ranked No. 1 in the film and cassette industries. The company fetched $780 million when it was sold.

Perelman’s emergence on the big-time takeover scene came with the siege of Revlon.

The firm, gloriously profitable during the days of founder Charles Revson, by 1985 was struggling under the leadership of the aloof, French-born Michel C. Bergerac. Bergerac was using earnings from Revlon’s core cosmetics business to sustain the growth of its new health-care units.

Perelman believed that he could find new value in the company’s cosmetics business, and made five separate bids for control. The management team, to defend itself, proposed a restructuring designed to sharply increase the value of shares.

At one point during the struggle, according to an adviser, Perelman declared: “We’ll win the company, because no matter what bid they put on the table, we’ll top it by 25 cents.” And ultimately he did win, with a $3-billion bid.

“He’s always been willing to spend what it takes,” said the adviser, who asked to remain unidentified.

Accused of ‘Greenmail’

Next was his fight for Gillette, which began in November, 1986, and lasted through the following August. Perelman made a $4.1-billion offer for the company but was stymied, said an adviser, when Gillette management threatened to put a 20% block of stock in the hands of a friendly third party.

Perelman sold his shares to the company for $43 million and was widely accused of taking “greenmail.” In his view, sale of the block was forced by management’s threat, which would have made a takeover highly unlikely and sent the stock into a downward spiral, according to the adviser.

Even as he was making a play for Gillette, Perelman launched takeover plays for two other firms, CPC International, a food processor, and Transworld, a hotelier and food vendor. Those bids failed, but Perelman eventually sold his stakes at handsome profits.

The investment firm of Drexel Burnham Lambert played a considerable role in his success.

Drexel junk bonds helped pay for the acquisition of Revlon. They were used earlier in Perelman’s leveraged buyout of the Pantry Pride supermarket chain and in the buyout of MacAndrews & Forbes, which is now holding company for various Perelman enterprises.

Though Perelman has roamed far and wide in picking his investments, he follows a pattern in managing the acquisitions. He looks for a large group of undervalued assets, often including valuable brand names. He buys control, sells off unrelated pieces, while keeping core, cash-producing operations, and installing reliable managers.

At Revlon, for example, Perelman brought back Sol Levine, an executive from the Revson era, to be president.

Increased Presence

Perhaps Perelman’s proudest success has been Revlon’s turnaround, in which he has been closely involved. The company has gained back market share in many areas, designed innovative products and advertising campaigns, and strengthened itself with a string of important acquisitions. Among them are the Max Factor and Charles of the Ritz cosmetic operations.

Revlon has greatly increased its presence in department stores, where it had begun falling behind competitors during the earlier regime.

The company’s sales are expected to reach $2.5 billion this year, from $1 billion in 1985, Revlon executives have said. They have predicted that the private firm’s operating profit will exceed $225 million by 1990, from $80 million in 1985.

But Perelman clearly does not intend Revlon to be his last major success. Wall Street has buzzed all year with speculation about how Perelman intends to use a cash hoard which some have estimated at over $2 billion.

This month, some speculated that he intended to pursue none other than Procter & Gamble, the consumer products giant. “All we know is that he’s out there, probably reviewing thousands of potential acquisitions to figure out which would work best,” said analyst Shore. “And for him, this investment in the thrifts is a drop in the bucket. There’s more coming.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.