1,000-Year-Old Ruins in Tucume, Peru, Compared to ‘Walking on Another Planet’

TUCUME, Peru — To famous Norwegian explorer Thor Heyerdahl, touring the ruins of Tucume “was like walking on another planet.” Now he is making sure that this otherworldly city is studied and preserved.

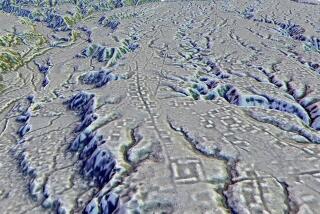

To visit the 1,000-year-old ruins of pyramids, temples and plazas today is to walk through an entire city from a vanished era.

In March, Heyerdahl’s Kon Tiki Museum in Oslo agreed to finance excavation and protection of the ruins, which are threatened by squatters, organized grave robbers and even state road builders in search of landfill. The museum is named for the balsa wood raft on which Heyerdahl crossed the Pacific Ocean in 1947.

Scientists say that excavation of the ruins could reveal technology applicable to modern-day agriculture and architecture in Peru. For instance, the ancient people grew crops more efficiently than modern farmers, experts say.

From the Panamerican Highway 1 1/2 miles away, the ruins look like huge mounds of earth. Up close, the hills turn into 26 eroded, brick, stepped pyramids. They tower above a visitor, one rising as high as a 12-story building. Huge ramps lead from the tops of the pyramids to open courtyards.

At its peak, Tucume was “a bustling concentration of temples, plazas, storehouses and civil residential areas,” said Walter Alva, a Peruvian archeologist who will head the excavations.

Thousands of workers were needed to make the millions of adobe bricks for the 543-acre complex, and construction of Tucume probably took centuries, he said.

Alva and Heyerdahl say they want to learn how the culture freed manpower to build such large monuments and how it traded with distant peoples.

Scientists believe the Lambayeque culture traded extensively with distant tribes along the Pacific Rim and in the Amazon jungle basin. Its artifacts used rose-colored shell from Ecuador, lapis lazuli from Chile and tropical bird feathers brought across the Andes from the Amazon basin.

The existence of Tucume has been common knowledge since 1532, when Spaniards wrote about the ruins after they arrived in Peru and conquered the Inca Empire.

Experts say the 200-mile swath of northern Peruvian coast, from Vicus to Trujillo, is one of the richest archeological regions in the world. Other ruins have more readily yielded pre-Columbian gold artifacts than Tucume.

An example is Batan Grande, a burial site also built by the Lambayeque culture that is visible from a hill near the Tucume pyramids about 10 miles away.

Tucume, perhaps the earliest urban settlement on the continent, appears to have been an administrative and political center, while Batan Grande served as the religious and burial center, Alva said.

Holes dug by grave robbers partially pockmark the ruins of Tucume, but the site has not been as heavily looted as others in the region.

Early this century, landowners would provide their guests with servants and tools and send them to dig for gold at Batan Grande and other ruins on their property, historians say.

That was the source of as much as 90% of the invaluable gold masks, ceremonial scepters, ear plugs and other objects displayed in the renowned Gold Museum in Lima.

The achievements of the Lambayeque culture in weaving, metal work and technology were “really unsurpassed, even to the time of European contact,” said Christopher Donnan, an archeologist at UCLA.

The ancients may have something to teach today’s culture.

Scientists say the pyramids are built of adobe bricks that alternate with logs from the algarroba tree. The design has allowed the pyramids to withstand devastating earthquakes for a millennium.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.