Ex-Allies Square Off in Court : Investments Spawn Bad Blood Between Former Colleagues in U.S. Attorney’s Office

The chief federal drug prosecutor in San Diego and a former colleague are in Vista Superior Court this week, locked in a bitter civil lawsuit sparked by a real estate deal gone sour.

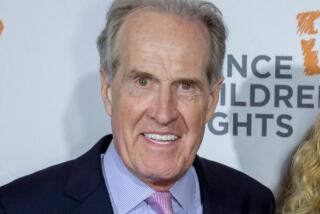

At issue is an allegation by Stephen Nelson, one of the most prominent lawyers in the U.S. attorney’s office for his successful drug prosecutions, that he was subjected to a smear campaign by the former associate, William Shaw.

For his part, Shaw told a jury Tuesday that Nelson, his former boss, abused his government post by using his influence to attract investors from within his office to join in large real estate transactions.

Furthermore, Shaw testified, “One could draw the conclusion that he (Nelson) was running a multimillion-dollar (real estate) business while drawing a full-time government salary.”

Nelson, 45, is a former chief of the criminal division of the U.S. attorney’s office in San Diego. He currently heads the narcotics division and serves as the regional coordinator for the Presidential Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Force.

The case has unveiled a close-knit group of past and present lawyers in the U.S. attorney’s office who invested in the real estate deals--including Peter Nunez, now the U.S. attorney for San Diego, and Jim Meyers, who is now a federal bankruptcy judge and separated himself from the group after his elevation to the bench. Other investors included federal drug agents and even several San Diego police officers who specialized in drug enforcement.

The investment group, operating on handshake agreements, invested in apartments in San Diego County, Texas and Arizona in deals collectively worth millions of dollars.

The group is now inactive, due both to a bottoming out of the real estate market in Texas and because the group’s activities were tainted by the litigation being resolved in Vista, according to those interviewed by The Times who were active in the group at the time.

Nelson, working with San Diego real estate salesman Pat McGinnity, was considered the point man in the investment group. Shaw invested in three of the properties: first in San Diego, while working for Nelson, and later in properties in Phoenix and Pasadena, Texas, a suburb of Houston, after he left government practice and moved to private practice in Los Angeles.

But the Texas apartment complex failed to make a profit, ultimately going bankrupt and, according to court documents, costing Nelson about $700,000 in personal funds after he bailed out his fellow investors.

As the Texas property failed, Shaw asked Nelson for his $136,000 investment back. Nelson said he didn’t have the cash available, however, and instead the two agreed for Shaw to exchange his interest in the Texas property for a larger interest in the Phoenix apartments, court documents show.

It was that failed investment in Texas that led Shaw in 1980 to file a lawsuit in Vista Superior Court, alleging that Nelson was guilty of fraud, breach of trust and violations of securities laws for, among other reasons, misrepresenting the details of both the Texas and Phoenix transactions, according to court files.

However, Nelson was never personally served with the suit, and Shaw dropped it in 1983 after he cashed out on the Arizona investment following a court-ordered sale.

Now Nelson is suing Shaw for malicious prosecution, abuse of process, and the intentional infliction of emotional distress against himself and his wife, schoolteacher Nancy Nelson. The couple lives in Del Mar. Among the charges by Nelson is that his wife suffered a miscarriage because of the stress brought on by Shaw’s ill-based litigation.

The case is being tried before Judge Don Martinson. Representing the Nelsons is attorney Milton Silverman, perhaps best known for his successful defense of Sagon Penn, who was acquitted in the shooting death of a San Diego police officer and the wounding of another officer and a civilian ride-along.

Shaw, who has retained several prominent San Diego law firms over the years, is now represented in court by Los Angeles attorney Timothy M. Thornton.

Among the allegations being made by Nelson is that Shaw filed the fraud lawsuit--but didn’t pursue it--simply because he wanted the leverage of the suit to get several government agencies to investigate Nelson’s real estate dealings.

Court documents show that Shaw complained about Nelson to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, the California Department of Real Estate, the California State Bar and the San Diego County district attorney’s office.

Among Shaw’s complaints, according to court records and testimony, was that Nelson finagled the purchase price of the Texas apartment complex--$3 million--in order to hide a $100,000 commission to McGinnity.

Besides Nelson, Shaw and McGinnity, other investors in the Texas property included Nunez, who at the time was an assistant U.S. attorney; fellow attorneys Michael Waltz and Bruce Castetter in the U.S. attorney’s office; then-Assistant U.S. Attys. Howard Allen and William Bower, and Curtis Burrell, now retired as an agent for the federal Drug Enforcement Administration.

None of the agencies contacted by Shaw found any wrongdoing by Nelson in the Texas transaction, court records show.

The San Diego County district attorney’s office, for instance, dispatched an investigator to Texas to look into the matter, at Shaw’s request. The investigation was “extensive,” then-Assistant Dist. Atty. Richard Huffman wrote Shaw in 1982.

“I have concluded there is no evidence of criminal fraud present in any of the material we have examined,” Huffman wrote.

The federal Securities and Exchange Commission found that the Texas deal “does not appear to involve possible violations of the federal securities laws,” then-Regional Administrator Michael J. Stewart wrote. That agency referred the matter to the U.S. Justice Department, where then-U.S. Atty. Jim Lorenz in San Diego said he found no merit to the charges, court records indicate. Current U.S. Atty. Nunez could not be reached for comment Tuesday.

The state Department of Real Estate determined there was no hidden $100,000 payment to McGinnity, but rather that it was an above-board transaction to which each investor but Shaw claimed knowledge, the department wrote in a letter to Shaw.

And a senior trial counsel for the State Bar wrote Shaw in 1983 that “there is insufficient evidence to support your allegations that the attorney (Nelson) was guilty of making misrepresentations” on the Texas deal.

Shaw, the first witness in the case, has been on the stand for about five days. Under direct examination, Silverman has challenged Shaw on the extent of his knowledge on the real estate transactions and his motives for filing the fraud suit against his client. Other witnesses in the trial, which is expected to last another two weeks, will include Nunez and Meyers, among others, Silverman said.

On Tuesday, for instance, Silverman asked Shaw why he filed the lawsuit but never pursued it--including not even serving Nelson with it. Shaw said he was concerned about the cost of the litigation.

Even though Shaw said he couldn’t afford to pursue the lawsuit beyond preparing and filing it, he said he felt obligated to alert the investigative agencies about Nelson’s activities.

“He (Nelson) has used his government position to assist him in finding persons to invest in his real estate ventures,” Shaw said.

Silverman asked him to explain how.

“Ninety-nine percent of the people (investing with Nelson) he hired at some point,” Shaw claimed. “He used government telephones to call around and used his government position. People invested in him because he had a government position and we assumed he would be trustworthy . . . . His position as my boss, my superior in the Department of Justice, was instrumental in my turning over a hundred thousand dollars blindly over to Mr. Nelson.”

Shaw conceded, however, that he continued to invest in both the Texas and Arizona properties even after he left the U.S. attorney’s office.

In his trial brief, Silverman has characterized Nelson as the son of working parents who “instilled in him the virtues of honesty, patriotism, service and hard work.”

An assistant U.S. attorney for 18 years, Nelson and his wife purchased a small fixer-upper duplex in Solana Beach in the early 1970s, and used the profit from the subsequent sale of the property to buy more property.

“Over the years, small duplexes became small apartments which became larger apartments, until Steve and Nancy, through their energy and initiative, had obtained some measure of financial security,” Silverman wrote in his brief.

Starting in 1974, Silverman said, Nelson and two co-workers--Don Shanahan and Meyers--began pooling their capital for real estate investments. McGinnity became the group’s real estate salesman, searching around San Diego County and later in Arizona and Texas, for investments that showed promise for quick turnaround profits.

Shaw, who joined the U.S. attorney’s office in 1974, joined the investment group in 1976 when it purchased a San Diego apartment complex. “Shaw, among others in the office, was aware that Nelson and Shanahan had done well in their real estate investments,” Silverman said.

The San Diego property was traded in 1978 “at a substantial profit” for the Phoenix apartment complex. Later that same year, the group looked to Texas and bought the apartments in Pasadena for $3 million. Shaw put up $136,000 on the deal--even more than Nelson himself, who contributed $113,000 toward the $525,000 down payment, records show.

The relationship between Nelson and Shaw soured as the Texas apartment complex failed to show a profit, Shaw traded his investment into the Arizona property, and then entered into a prolonged debate with Nelson over whether his dollar-for-dollar trade was a fair swap for Shaw, given discrepancies over the value of the Arizona property.

The fraud suit Shaw filed in Vista in 1980 was intended to be attached as an exhibit to Shaw’s complaints to the investigatory agencies, Silverman claims in his brief. Those complaints, Silverman argued, “were intended to bring Nelson to his knees (by forcing the sale of the Arizona property) and to destroy him professionally and financially.”

In his defense brief, Thornton wrote that Shaw properly filed the fraud suit against Nelson in 1980 based on his own investigation into Nelson’s real estate dealings and because he was advised by various lawyers--including Phoenix attorney John J. O’Connor III, the husband of Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor--that he had grounds for a lawsuit against Nelson.

Silverman is seeking unspecified monetary damages from Shaw on behalf of Nelson.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.