Book Reviews : Columnist a Loose Cannon on Journalism’s Deck

Corruptions of Empire by Alexander Cockburn (Verso: $22.95; 479 pages)

A gadfly needs a bullock. To package nearly 500 pages of Alexander Cockburn’s zigzag attacks on our lumbering institutions--press, politics, culture--is to immure a swarm of aerial maneuver in a space too small for any of the targets to fit. It is like having a quart of meat-tenderizer and not much meat.

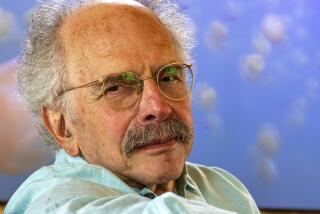

Cockburn, a lordly man of the left who reminds us of his Anglo-Irish gentility whenever possible, can be very patronizing about journalism, particularly when it takes itself seriously. He is a quintessential journalist, though not of the avowedly responsible kind that remains the ideal in the United States.

He is a pamphleteer, a loose cannon or water-pistol, an intermittently indispensable jeerer; but he remains a journalist in the most basic sense of the word. He depends upon dailiness, or, in his case, weekliness--he is a columnist for The Nation and the L.A. Weekly--for his material. The weeks, plodding by with their comfortable loads of assumptions, are his bullocks.

A Largely Unfeasible Project

This makes “Corruptions of Empire” a largely unfeasible project. It is a massive anthology of past occasions; a family album devoted almost exclusively to photographs of last year’s fireworks (they go back to the mid-1970s, in fact). On the other hand, it does provide a portrait of a commentator who continues to light up, annoy and sometimes poison our travels through the present.

Cockburn’s style may be more significant than his politics. His style, like that of two Anglo-Irish predecessors--Wilde and Shaw--is to shock wittily. He would probably prefer the Shavian comparison, because he takes, or seems to take, his politics quite seriously. Certainly, his stance on the left gives him, in the American context, a lot more shock-opportunity.

His funniest, if not his fiercest attacks are upon liberals and mild Socialists. I don’t believe that in the entire book there is a line against any one of the current left-wing dictatorships.

It is hard not to suspect, though, that this is itself a matter of style. It would be trite and fuzzy, and would dampen the glee, to introduce the note of qualification that seems to be lurking somewhere. As Cockburn writes, referring to American journalism, “Evenhandedness becomes a degenerative disease.”

Tribute to the Late Larry Stern

Elsewhere, paying tribute to the late Larry Stern of the Washington Post--a tribute that Stern probably would have ended up forgiving him for--he writes: “A Trotskyist in his hot youth, Larry knew what the facts were going to tell him long before he discovered what they actually were.”

This, of course, is Cockburn’s own code; one that he cheerfully avows. He berates his own host, The Nation, for headlining a piece on a political agreement among the Nicaraguan Contras: “A Fragile Unity is Born.” “Let’s get this straight,” he writes. “ Our side gives birth to fragile unity. Their side cobbles together a makeshift coalition.”

Commissar Cockburn? Not quite. He has put on his commissar’s suit, he invites you to notice that he is wearing it. He is, you might say, an intellectual dandy; or you might say that he uses words and ideas as a cartoonist uses drawings, with outrageousness and exaggeration combining to make an artful point.

Cockburn is snobbish, funny, brutal and nostalgic. He is a figure more recognizable in English journalism than in ours. His style is close to that of Auberon Waugh and the writers for Private Eye. (He uses Private Eye-style epithets: “The revolting Pat Buchanan.”) They have spoken of themselves as Tory Anarchists and that, of course, is what Cockburn is.

Feudal Touches Creep In

Unlike theirs, his bile and his wit proclaim themselves of the left. But an occasional piece expressing a bit of Marxian political analysis is invariably plodding and spiritless. What he likes--and the writing brightens up--is to use Marx to smite liberals, conservatives, capitalists, media stars and modern life in general. Feudal touches creep in; he reminds us of the posh prep school he went to, of his family’s “ancient Tudor house,” of his ancestor Sir George Cockburn, who burnt the White House and an offending Washington newspaper office in the War of 1812.

Cockburn fancies himself doing the same: American politics and the American press are his steady targets. And his Marxism has a Tory-like human dimension. His father, Claud Cockburn, was a noted English Communist journalist who led a stormy and picaresque life. Young Cockburn is continually recalling him, and quoting him. He brandishes intransigence as if it were an act of filial piety.

Some of the most engaging passages in the collection are Claud Cockburn antidotes.

Cockburn’s Tory-Left-Dandyism can be tiresome, brutal and often plain dumb. He is an arrogant Regency Buck at our journalistic festivities; you may not forgive him, but you may also reflect that three-button tweed has its own constrictions, and its own arrogance.