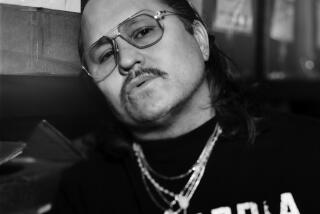

Tough Being Man in Middle, Ex-Contra Chamorro Says

- Share via

MANAGUA, Nicaragua — During his first week back in Nicaragua after seven years of exile, former Contra leader Edgar Chamorro met a hostile cattleman who warned him that the Sandinista government would use him “like a rancher uses one steer to corral all the rest.”

At a dinner party, a businesswoman angrily told Chamorro it would be best for everyone if “you keep your mouth shut.”

A Sandinista radio commentator interviewing Chamorro about his experiences with the CIA and the Contras called him “a criminal” and asked how he felt, “knowing that so many civilians have been killed or maimed” in fighting between Contras and the Sandinistas.

If Chamorro has learned anything in his week of testing the political waters in Nicaragua, it is how difficult it is to create a political center in a country at war.

“People are trapped in extremes,” he told an interviewer.

Chamorro, who was expelled from the Contra leadership body in 1984 for publicly criticizing control exercised over the rebels by the CIA, arrived here last week to apply for amnesty under a Central American peace plan and to explore the Sandinistas’ commitment to the democratic reforms called for by the plan.

He sees his as a test case for others waiting to see if it is safe for them to come back to their Nicaraguan homeland.

As a proclaimed anti-Sandinista who became a proclaimed anti-Contra and testified against the United States in Nicaragua’s 1985 case against Washington before the World Court, Chamorro is likely to arouse suspicions in the polarized society here.

Managua, like its politics, has no center. The old city center was destroyed by an earthquake 15 years ago and has never been rebuilt.

Chamorro tours what’s left of the old city and the newer suburbs like a surveyor, measuring political space. With the Contras, he specialized in media manipulation and psychological warfare, and now he watches for the reaction to what he says in the name of peace.

Barricada, the Sandinista party newspaper, announced Chamorro’s return on its front page, under a small headline at the bottom of the page.

“It is to their advantage to be perceived as people of peace,” Chamorro said. “But they didn’t overplay it. They don’t want to make me a leader.”

El Nuevo Diario, a pro-Sandinista newspaper, published a story about his return on its back page. The opposition newspaper La Prensa published nothing about it at all.

“They are people who want to ignore me.” he said. “It’s not fair, because it (his return) was news.”

Chamorro said that so far he has only first impressions of revolutionary Nicaragua and that they are as mixed as the reaction to his return.

When he tried to take a nostalgic peek at his old home in the well-to-do neighborhood of Las Colinas, he found he could not get near it. The Interior Ministry, which oversees state security, has taken over a house nearby, and soldiers have closed off the street.

“The military should be in the barracks,” Chamorro said. “There is not a clear distinction between military and civilian.”

As bad as the blocked street, he said, is the U.S. Embassy compound, which looks like a prison.

“There is a wall with ugly-looking barbed wire and then a second wall with bigger wire,” he said. “They are closing themselves in.”

On a drive through Managua, Chamorro took note of the large numbers of uniformed men and women in the streets but pointed out that many are unarmed and, as he put it, unthreatening. He pointed to a soldier sitting against a tree with a rifle across his lap, chatting amiably with a civilian. Close by walked another man in fatigues, without a gun, and a third carried a briefcase.

“They’re skinny guys in green,” Chamorro said. “You don’t know what it was like to see a National Guardsman with a gun.”

This was a reference to the old days, when men in uniform here belonged to the National Guard, whose officers the United States helped train and whose commanders usually were dictators of the Somoza family. Anastasio Somoza, the last of the dynasty, was toppled by a popular revolution in 1979, with the Sandinistas in the vanguard.

Chamorro recalled that Managua was poor and run-down when he left. Today it is still poor, and more run-down, and its population has tripled, with tens of thousands of migrants from the countryside. Chamorro is appalled by the shortage of public transportation and the long lines of people waiting for buses or hitchhiking.

“They call themselves the popular government,” he said. “I can’t believe they can’t do something to improve the transportation.”

He said that people have been generally friendly to him, that they have spoken openly of their likes and dislikes about the Sandinistas.

At the Roberto Huembes market, where he stopped, two women selling lemonade were asked if they would vote for the Sandinistas in new elections. One woman nodded yes. The other, whose husband was about to be drafted into the army, shook her head no.

“We just want the war to end,” the Sandinista supporter said.

The women said that in past years, housewives had money but there was a shortage of food. Now, with triple-digit inflation, they have no money, but there are plenty of things to buy.

Chamorro carefully examined a 20,000-cordoba bill, which was a 20-cordoba bill with three additional zeros stamped on. After lunch with a companion at a restaurant, he shook his head over the check, which totaled 152,000 cordobas.

“When I left, you could buy a house for that,” he said.

A Chamorro cousin, Carlos Coronel, another former Contra who accepted amnesty about a month ago, has offered Chamorro his analysis of the political situation and his advice. Soon after Coronel came back, he was called in for questioning by state security officials.

“Carlos made it clear that he took amnesty but was not here as an informer,” Chamorro said. “They didn’t push him.”

He said his greatest joy back in Nicaragua is in renewing relationships. When he saw an 82-year-old uncle, Jose Coronel, it was “like walking into paradise.”

“I felt a happiness I haven’t felt in years,” he said.

Chamorro sounded optimistic in an environment where there has been little optimism, moderate in a place of little moderation. He has been careful in his first days not to provoke the Sandinistas--perhaps too careful if his intention is to test the limits of democracy.

In his Sandinista radio interview, Chamorro attacked the United States and the Contras, saying that the insurgency “robbed Nicaragua of its national pride.” He said he believes the Roman Catholic Church and the staff of the newspaper La Prensa have been infiltrated by the CIA and that he does not believe the leaders of either are aware of it.

He trod lightly on the Sandinistas. In one of two references to the Soviet Union, Chamorro said that Nicaraguans must not “fall into the colonialist mentality of working for foreign powers.” He urged a conciliatory stance toward the government of Honduras, which allows the Contras and their CIA network to operate from its territory.

Led by the interviewer, Chamorro urged other Contras to put down their guns and come home.

At the end of the show, he received a call from Sandinista television asking him to appear the following day.

“I just got here,” Chamorro said.

Then he said: “Radio can provoke strong emotions. This was the voice of the Sandinista party. The fact that they invited me to be on at all is amazing.”

“I know people hunger for different leadership, that is more down to earth, with less rhetoric and more common sense,” Chamorro said. “It is not me that people want. It is the idea.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.