Economists Assail ‘Sensible Growth’ Initiative

- Share via

A proposal to tie future development in Orange County to builders’ willingness to foot the bills for street and highway systems could have a chilling impact on the county’s $50-billion annual economy, according to economic researchers at Chapman College.

James Doti, dean of business and acting president of the private college, said in a speech Wednesday that economists at Chapman’s Center for Economic Research believe that the policies in the “Citizens’ Sensible Growth Initiative”--being circulated for qualification on the June, 1988, ballot--would lead to a new round of housing cost increases and a sharp decline in the already-slowing growth of local employment and incomes.

Those trends in turn would lead to a decline in the county’s tax base and the amount of money available to maintain county services and systems, Doti said in a luncheon talk in Irvine before the local chapter of the Town Hall of California.

Instead of government-imposed levies on builders, Doti said, the county should turn to direct-user fees, such as toll roads and higher gasoline taxes. The county and its cities should also streamline government planning processes so developers can reduce the amount of money they routinely set aside now to pay finance costs on their loans while their projects are being processed.

While the public tends to believe that builders are paying for roads, schools, parks, sewer systems, police and fire services and other such elements, Doti said, most of the costs are passed on to individual home buyers.

Doti, whose economic theories were nurtured at the University of Chicago under conservative economist Milton Friedman, is a proponent of minimal government intervention in the market process.

He cited a recent Building Industry Assn. survey to bolster his argument that government-imposed fees and land-use limits have artificially raised housing prices in the county to near-dangerous levels.

“It has been estimated,” Doti said, “that roughly 30% of the price of a home in Orange County pays for various taxes, development fees and the costs involved in the lengthy building approval process.”

The BIA survey of government-imposed development fees, he said, found that charges directly related to building a project have increased by 219% in California in the last 12 years. During the same period, the survey found, charges levied on developers to help pay for county services and systems have soared 559%.

Proponents of the slow-growth initiative, which was developed by a Newport Beach-based group called Orange County Tomorrow, want to preserve the “environmental quality and aesthetic appeal” of the county and want to clean up the county’s traffic “mess,” Doti said.

But opponents of the measure want the same things, Doti argued. “The only real disagreement involves determining who should pay. . . . Advocates of the Sensible Growth Initiative apparently believe developers and property owners should pay,” he said, but data such as that developed by the BIA and Chapman’s economic research center “suggest that these parties are already paying a disproportionately high share.”

While the median price of a resale home rose 7.3% nationally in 1985-86, to $83,800 from $78,100, resale home prices in Orange County shot up 14.3% the same year, to a median of $157,748 from $138,000, Doti said. The median is the point at which half of all homes sold for more and half sold for less.

(In a study released earlier this month, the Center for Economic Research--which developed the nation’s only computerized model of a single-county economy--said the median price of a resale home rose an additional 6% in the first three months of 1987, hitting $167,280 in the second quarter. Nationally, the median rose just 1.3% to $85,800, the center reported.)

A recent study by the California Assn. of Realtors found that just 29% of the households in Orange County had the minimum annual income of $52,864 needed to afford the median-priced resale home in the county--pegged at $168,656 in July.

The growing gap between what current residents can afford to buy and the price tags on the homes offered for sale in the county has had a measurable downward pull on jobs and income levels, Doti said.

The rate of job growth in the county, he said, has dropped by almost 43% since 1980 from the boom period of 1971-80, while the decline in annual employment growth nationally and statewide has been less than 15%.

And since 1981, Doti said, almost 75% of the 54,400 new jobs created in the county have been in industries paying average wages 30% below the national average.

“The lower rate of housing affordability, which appears linked to the increased use of various development controls, has tended to push capital intensive, more productive and higher-paying manufacturing jobs out of the county,” Doti said.

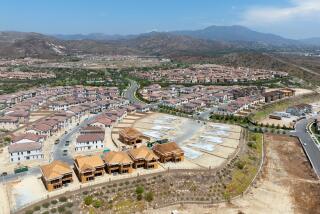

Many of those companies, Doti said, are following displaced Orange County residents into Riverside and San Bernardino counties, where housing costs are much lower.

Most of the new jobs in Orange County, he said, are in the service and retail trade sectors, where “pay and productivity are a great deal less than union scale on an assembly line.”

Calling the employment trend “disturbing,” Doti said that it has caused per-capita personal income to grow at a slower rate in the county than nationally since 1981.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.