Major Cancer Research Step Heralded at UCSD

In what is believed to be a significant step toward understanding the genetics of cancer, a team of young researchers in San Diego has cloned and analyzed the structure of a newly discovered gene that may serve to block the development of cancer in humans.

The gene, which has been the focus of intense competition among research teams in the United States and Canada, was first cloned last year by a group in Boston. Now the UC San Diego group has “sequenced” the gene--that is, sketched its structure and nucleotide sequence.

Such an analysis is an essential step toward fathoming the functioning of the gene, which is the first cloned gene with a proven role in causing cancer. It opens the door to identifying the protein by which the gene works and eventually applying that knowledge toward treatment.

The research, published today in the journal Science, concerns the gene responsible for retinoblastoma, a potentially fatal eye cancer in young children. Because survivors often develop other cancers later in life, researchers suspect the gene has broader significance.

It is believed to be unlike other known cancer genes, or oncogenes. Whereas those genes cause cancer by becoming activated and functioning in an abnormal fashion, the retinoblastoma gene appears to trigger cancer by losing its ability to function.

That attribute raises the possibility that, if researchers could introduce missing DNA pieces to the defective cells, they might eventually be able to convert cancer cells into normal cells, said Wen-Hwa Lee, who heads the six-person team at UC San Diego.

“This gene may be a general cancer suppressor gene,” Lee said in an interview on the La Jolla campus this week. “ . . . If that is the case, there are many, many applications in terms of cancer therapy.”

“It’s important in that it is not ‘just another oncogene,’ ” said Dr. Stephen Friend, a researcher at Harvard University and the Whitehead Institute in Cambridge, Mass., who cloned the gene last year. “It’s a different mechanism, a different process by which a gene can form a tumor. It is our understanding that this will be a common mechanism in a number of cancers, such as breast cancer and leukemia.”

Researchers have been investigating the retinoblastoma gene for decades, and in the 1970s found its approximate location. In the early 1980s, a handful of groups began to compete to be the first to find and clone the gene.

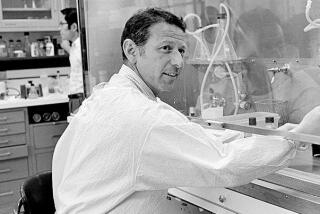

Lee, 36, a molecular biologist, was part of a team at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. In 1984, he moved to UCSD to form his own group and start from scratch, competing directly with an old friend who took his place in Los Angeles.

The following year, Lee cloned a gene believed to be located near the retinoblastoma gene on a chromosome. Then he began the meticulous process of “chromosome walking,” searching adjacent genes for the identifying defects observed earlier in retinoblastoma tumor cells.

But Friend and his team beat Lee to it: They reported last October that they had cloned the retinoblastoma gene. “It was awful,” Lee recalled this week. But his lab, too, cloned the gene shortly afterward and forged ahead with the next step, sequencing.

Now, Lee’s group insists that it has more “precise evidence” than the Boston group had that it has indeed cloned the correct gene. In addition, it is the first to sequence the gene--a task that the Boston and Los Angeles groups also have undertaken.

“Sequencing is an absolutely necessary step in fully understanding the gene,” said Lee’s colleague, Robert Bookstein, a 30-year-old M.D. and post-doctoral fellow. “The sequence specifies the predicted protein . . . and the protein is how the gene functions.”

“I am thrilled that they have been able to confirm our work and have been able to take it the next step, to publish the sequence,” Friend said Thursday. He characterized the work as “not a new leap” but “an advance, to be able to study the protein further.”

Friend said the next step for researchers is “trying to understand why the gene does what it does. That’s a functional question, not a structural question. That has to be understood before any talk about therapy or benefit to people is discussed.”

Speculation about how the gene functions includes theories that it might regulate other genes or control cell development. If that were the case, cells might proliferate and form tumors if the gene’s controlling function were lost.

“If this is responsible for suppressing the other kind of oncogene and you lose the control, the other oncogene goes on, causing the cell to start proliferating wildly,” Bookstein theorized.

Asked about the widespread interest in the retinoblastoma gene and the competition among researchers to be the first to understand it, Lee and Bookstein cited both the potential significance of the gene and the pressures of scientific research in the United States.

“Because cancer theory is mysterious and so many people have worked so hard to understand cancer,” Lee said. “This (gene) is the best and model system. Everybody is trying to understand what is going on here. That is an enormous challenge in your brain.”

“It’s open competition for getting things done,” Bookstein said. “And if you don’t succeed first or second, you don’t get money. And if you don’t get money, you can’t go on.”

He added: “I think we will have established ourselves as major contenders. . . . It automatically gives you more prestige in trying to get further grants and further money. You have to. It’s sort of the survival of the fittest in science.”